Have you ever had the feeling as you walked outdoors that a secret world existed that you might not be fully aware of?

No, this isn’t some crazy conspiracy theory. I’m referring to the vast landscape of edible delicacies hiding right under our noses — and doorsteps. You don’t have to live in a rural area to find them, either. New England is full of tasty wild foods to forage, and spring is a great time to look for them.

Weeds, or wonderful eats?

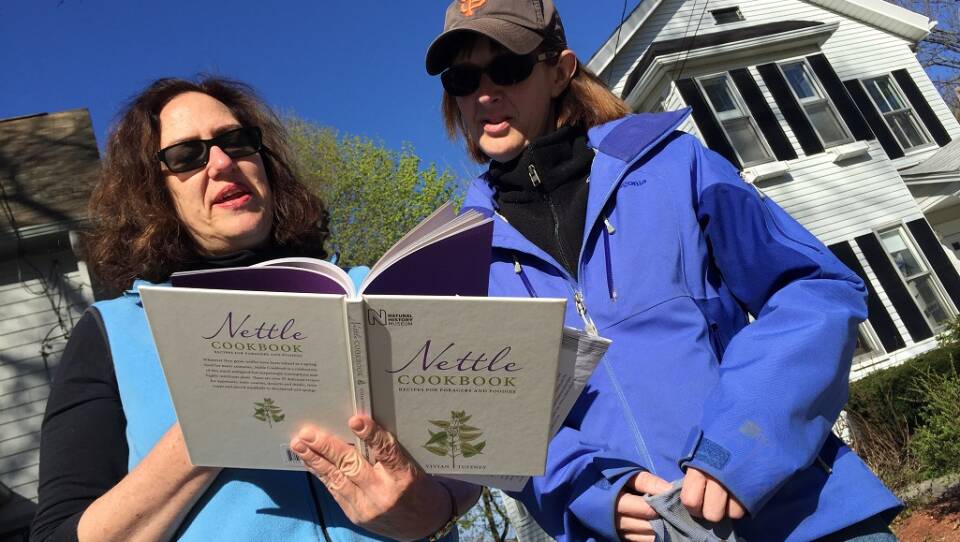

Ingrid Gallagher and I are walking through her Arlington neighborhood on a sunny day in April. The birds are singing, green shoots and flower buds are everywhere; it’s the perfect time of year to look for stinging nettles. “I always loved being outside,” Gallagher says. “I love the woods and cooking and eating. Foraging is an extension of that.”

Gallagher remembers her grandmother foraging for tender new dandelion greens every spring to make a salad. “Nettles are really great, too, because they’re coming up at that time of year when you’re craving something green,” she explains, “and yet it’s still cold enough that you want something warm and comforting… if intense green could have a taste, it would taste like nettles.” Gallagher likes to add blanched nettles to potato soup and blend it to a velvety texture, resulting in what her husband and daughter call the “world’s best soup.” It’s something they look forward to each spring, much like her grandmother’s dandelion salad.

Notice a pattern here? Stinging nettles, dandelions… some people would be horrified to find these weeds growing on their property. But there’s a saying: If you can’t beat them, eat them. Many of the edible plants locals hunt for are considered weeds and invasive species, but they also happen to be delicious. For example, wood sorrel is light and lemony; lamb’s quarters is a wonderful substitute for spinach; Japanese knotweed tastes and can be used like rhubarb; and true to its name, garlic mustard has a spicy kick. These plants also pack a highly nutritious punch — they’re full of vitamins and minerals our bodies crave after a long winter eating heavy, carb-loaded fare.

The outdoorsy type

Foragers seem to have one thing in common — they love spending time outdoors. But there’s more to it than that. “I like that it can lead to culinary adventures,” says David Craft. “When you’re a vegetarian or vegan — I’m somewhere in between — you’re always looking for more options. But I’m very practical… adding foraging to my time spent in nature means I’m being productive and learning new things, which goes with my personality.” Craft is an assistant professor of radiation oncology at Harvard Medical School. He also wrote a book called Urban Foraging and leads foraging tours in the Boston area.

Craft, who started eating wild edibles almost a decade ago, also gets a kick out of dining for free. “I’m a cheapskate, and I thought [foraging] would be fun,” he grins. As we walk through a local park on a damp afternoon, he points out a variety of plants and describes how to use them. His favorite is pokeweed, which looks a bit like asparagus and needs to be boiled for ten minutes before you can eat it (otherwise, it’s poisonous). Craft jokes that perhaps that might be why he likes it so much, and describes it as having a slightly sour, iron-like flavor. He’s gathering ingredients for a foraged dinner event at a gallery he co-founded in Cambridge. The meal, prepared by guest chef Paul Lang, includes burdock root, Jerusalem artichokes, stinging nettles, watercress, chickweed, chicory, violets and Solomon’s seal shoots, all foraged locally.

Pam Kristan also likes to cook with what she finds in the wild. She usually does two foraging tours a year for the Franklin Park Coalition, serving attendees nettle soup and knotweed crumble in the spring and acorn bread in the fall. Kristan runs a business leading time management workshops for the non-profit sector, and has always loved learning about plants. In the seventies, she lived off the land for a few years in northern Maine before moving to Portland, then Boston. “It was sort of the best of times and the worst of times,” she remembers. “There were a whole bunch of abandoned farms with apple trees… we’d make cider, and gather clams and goose tongue greens.”

In terms of how to forage safely, Kristan claims most of it is just common sense. Her advice is to gather wild goodies away from and uphill of highly traveled roads, otherwise they may be covered in exhaust and pesticides. Other places to avoid foraging near include: railroad tracks, dumping grounds for fuel and batteries, and places where there are a lot of dogs.

Kristan especially enjoys when local linden trees come into flower. “In June,” she explains, “there’s a day when you wake up and smell them, their wonderful perfume.” The flowers can be harvested to make tea, be added to vodka to make a tincture, or get boiled with water and sugar to make a syrup. Kristan suggests adding linden flower tincture and syrup to fizzy water with a squeeze of lime for a delightful summer cocktail. “Linden is medicinal,” she adds. “It lifts your spirits.”

Living off the land

According to Netta Davis, who teaches a class on wild and foraged foods for Boston University, humans have been foraging throughout their entire existence. But it’s a common misconception that local Native Americans survived solely by hunting and gathering. “Early indigenous people in New England were terrific gardeners,” explains Davis. “I don’t know whether they would have referred to it as farming, but they certainly cultivated their crops.”

By contrast, the Puritans and Pilgrims who settled in New England in the 1600s had to learn how to farm from scratch. They supplemented their diet by fishing, hunting and trapping. In addition, they learned from the native population which berries, nuts and plants were safe to eat. Local favorites include the American cranberry, wild blueberries, beach plums, ground nuts and shellfish.

Yet, in an age when so many people have access to such a wide variety of foods throughout the year, why do we still forage? “I think to some extent it feeds a deep-seated instinct we have as humans,” says Russ Cohen. “You might call it atavistic… Remember, [for] the vast majority of our existence on earth, we were hunters and gatherers, and it’s only been relatively recently that we’ve left that behind.” Cohen is quite possibly the best known forager in New England; he's been teaching people about wild edibles for over forty years and is the author of Wild Plants I Have Known…and Eaten.

Over the past decade, Cohen has noticed an uptick in the number of people interested in both learning and teaching about foraging. In addition to the outdoorsy type, he says, “There are the do-it-yourself people who want to connect to food directly by growing it in their backyard, keeping beehives, brewing their own beer...” And then there are the people Cohen sees as a potential threat to local plant life — those who go into the woods and see dollar signs. “I’m seeing these wild plants becoming articles of commerce because restaurants look at this as cashing in on the wild food craze,” says Cohen. He warns against irresponsible foraging, which threatens the existence of local delicacies like wild ramps.

When it comes to foraging etiquette, the experts agree it pays to be ethical. It’s good form to ask permission before you forage on someone’s private land. If you come across a rare plant, either don’t touch it or take only 10 percent and leave the rest. When it comes to wild ramps, Cohen urges people to cut off one leaf per plant and leave the bulb in the earth so it will grow back the following year.

If you’re looking to jump on the foraging bandwagon, it’s best to learn by example. That’s why Cohen, Craft and Kristan all lead local foraging tours. It’s one thing to study photos and read up on plants, but once you’re out in the field, it’s another story. It helps to have someone there to confirm that what you’ve gathered is safe to eat. Start small and be patient as you nurture your burgeoning foraging knowledge. Pretty soon, you won’t be able to walk anywhere without seeing a potential meal beneath your feet.

For more information and to learn about foraging tours in your area, visit users.rcn.com/eatwild/sched.htm, foragelive.tumblr.com and franklinparkcoalition.org.

Follow Amanda on Twitter @amandabalagur.