It’s not a position you’ll find at most organizations – Executive Director of Accessibility – but it’s one that GBH’s Donna Danielewski relishes. Over nearly two decades at GBH, she’s helped continue the Foundation’s long tradition of leading the way in media accessibility — from closed captions and audio descriptions to legislation, community events, and more.

On the heels of Disability ReFramed: A Growing Community, a GBH-hosted panel centering the challenges, joys, and support networks that accompany life with disability, we sat down with Donna to talk about Disability Pride, what brought her to GBH, her passion for accessibility, and public media’s place in the fight for disability rights.

This year marks the 35th anniversary of the ADA’s passage into law. Why do you think celebrating Disability Pride Month is so important at this moment?

Number one, people in the disability community are frightened of the changes that could potentially impact them through current legislation.

Two, centering joy and celebrating the community of people with disabilities, and how we can all support one another, is key right now because building community really matters and makes an impact.

For example, the way that [Disability ReFramed panelist] Keisha Greaves talked about her experience was particularly powerful. At first, she said she lied about [her disability diagnosis], saying it was an injury, not coming to her power as a disabled person, and claiming that identity until she was ready. It’s not dissimilar from Pride Month in June: this is when people get to really claim and embrace their identity.

Being able to host an event like [Disability ReFramed], calling on our wealth of experience and expertise with accessibility and disability, was a really proud moment for GBH. I’m so proud of the entire organizing team, and all the hands at GBH that made it possible. This is a place where these conversations belong.

Where did the title “Disability ReFramed” come from?

We wanted to look at disability through a different lens, exploring the angles and perspectives that don’t get told all the time. For us, it was important to do it from a place of joy — how can we create a place where everybody moving through this journey can learn from one another, without putting too much of a burden on people with disabilities to be the teachers.

We also created a living resource document to share with attendees and anyone else, directing folks to programs and organizations (including the nine groups that tabled in GBH’s Atrium during the event) that can help them navigate these difficult times.

What were some of your favorite moments from the event?

Tina [Zhu Xi Caruso] cracked up the whole audience when she closed out the evening by thanking “viewers like you.” She spun right into our own script!

The audience question, “What do you love about your disability?” was one I hadn’t heard before, and I’d like to include it in our events going forward. It opened a door to a different perspective for our guests and panelists.

And when Carl [Richardson] said “the younger generations,” give him hope, that choked me up a little.

In what ways has GBH been a pioneering force in accessibility and media?

It started in the ‘70s with some brilliant people working with the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services to think about how disabled folks could access newer technologies. GBH, of course, pioneered captioning for broadcast television and audio description for film and television.

There’s a long list of “firsts” in media accessibility that GBH led the way on. We produced the first children’s show with captions with GBH’s ZOOM; we wrote the guidelines used by universities and testing companies for how to create accessible educational and STEM content; we worked with Universal/Motown Records to create the first audio described music video, Stevie Wonder’s So What the Fuss, voiced by Busta Rhymes — it is so good!

GBH built a reputation as a leader in the accessibility space that we’ve maintained for this long, and we’ve partnered with different accessibility organizations and advocacy groups for years, helping advance important legislation such as the CVAA (The Twenty-First Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act) in 2010.

You started at GBH in 2008. What brought you here?

I was working at a research firm in Cambridge for 10 years. It was a very high-powered job that I enjoyed. But when my third child was diagnosed with hearing loss at birth, I suddenly had the experience that many have, which is being a full-time employee, and also having a second job learning how to be a mother of a disabled child.

I wanted to make a change that offered me a better quality of life and gave more space to my family. I remember telling a colleague at my former company that GBH was a dream place to work for me — as an English Ph.D. and a big MASTERPIECE fan. And she said, “you know that’s where captions started?” So I began dipping into the history of accessibility at GBH and knew it was where I belonged.

What has your work involved over the years at GBH?

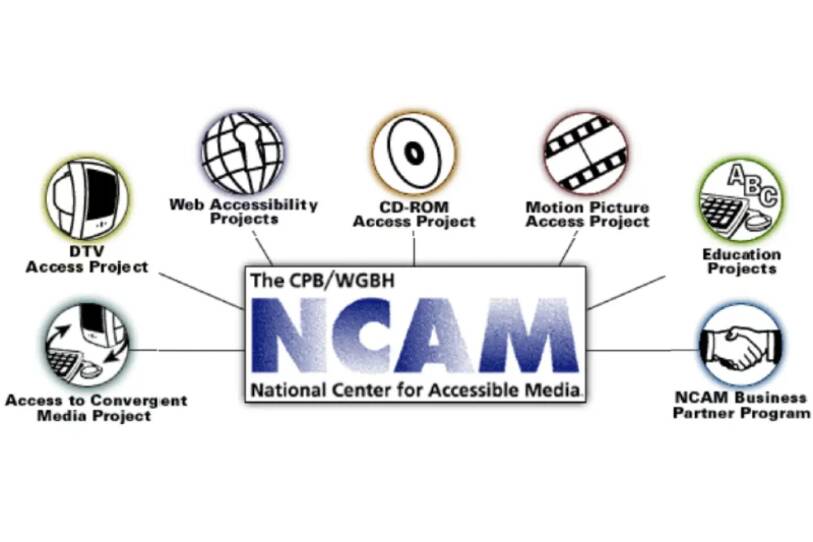

I started in GBH’s National Center for Accessible Media (NCAM) and worked there for 14 years, shifting from a fully grant-funded federal research model to a self-supporting consulting business.

But for as much as NCAM provided consulting to people inside GBH on specific projects, as well as so many external clients — from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, museums, educational publishers and test makers to Broadway shows and the NFL — we didn’t have an overarching person paying attention to accessibility and disability at GBH more broadly. So, GBH leadership created the Executive Director of Accessibility position.

I’ve been able to care for our employees, viewers, members, and visitors, while also paying attention to all of the content we’re putting out, ensuring it’s accessible. On any given day, I’m on the phone with a consumer from any part of the country who’s trying to access audio description on our shows – literally FaceTiming with them while they’re adjusting their TV settings – or working with PBS and other distributors to make sure that our material is disseminated with captions and audio description in all formats.

At the same time, I’m also helping plan and put on events like Disability ReFramed and overseeing our Disability and Accessibility Employee Council, GBH All Access. There’s never a dull moment; my job varies so much from day to day. I can’t complain, though. It’s been nothing short of a dream career path.

Why do you think public media, and GBH specifically, has taken up this mantle of media accessibility?

Because public media is for everybody, and everybody includes people with disabilities. Our mandate is to serve the nation, and more than a quarter of our nation identifies as having a disability. It’s imperative that our content is accessible to people with disabilities through captions, descriptions, or American Sign Language. GBH has always taken that mission very seriously.

But, as you can read on the side of our building, we’re also telling stories of diverse communities and telling them with accurate, authentic representation. That’s across the board, down to our kids’ shows.

Work It Out, Wombats! just introduced a character with a cochlear implant, voiced by a young woman actor who has a cochlear implant. And they consulted with NCAM to think about how an animated snake would communicate via sign language — these are the important questions we wrestle with every day!

But it really is so important in public media that we reflect the audience that we serve, and serve them faithfully by ensuring that everybody can access our programs and services.

On the GBH News side, the impact of reporter Meghan Smith’s work on the disability beat cannot be understated. That is a groundbreaking change at GBH over the past three years. She has built trust in her storytelling by being out in the disability community, at events and hosting listening sessions where she inquires about story topics, relevant issues, and coverage. Not just about how they want their stories to be told, but what other stories deserve attention — because ultimately, every story is a disability story.

How has public media touched your life as a parent?

When you’re raising a family with three kids, public media is indispensable. Through public media, my kids were able to see themselves in these characters, including my youngest, who has hearing loss and autism.

It absolutely made my life easier as a parent. I think that’s a big gift that public media gives the world — I don’t want to say helping to raise the children of America, but a little bit! And mine were among them.

Learn more about GBH’s commitment to accessibility in media, as well as the timeline of GBH’s leadership in media accessibility over the years, and watch AMERICAN EXPERIENCE’s Change not Charity: The Americans with Disabilities Act.