Fifty years ago, on Oct. 21, 1975, the Boston Red Sox played one of the greatest World Series games ever.

The Sox hadn’t won a championship in more than half a century. That night, they were down three games to two against the Cincinnati Reds, desperate to tie it up and force a Game 7.

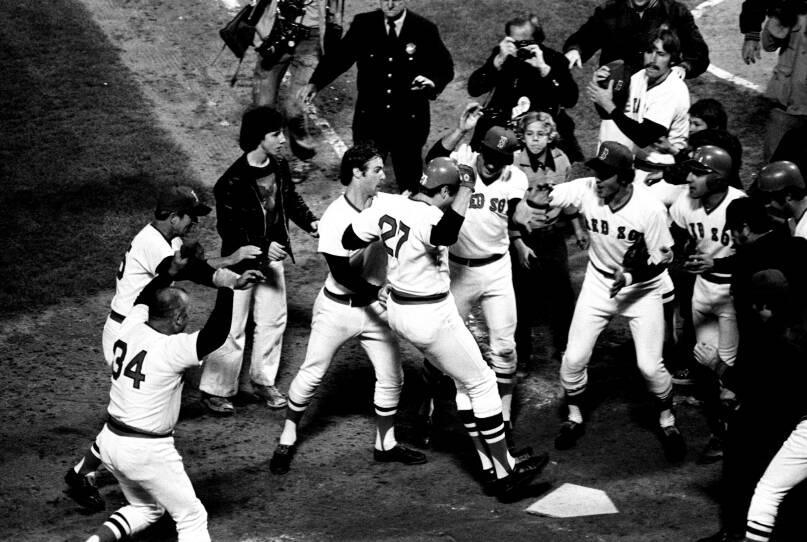

In the bottom of the 12th inning, Carlton Fisk stepped to the plate.

Carlton Fisk slams a 12th-inning home run. (AP Photo/Harry Cabluck, File)

Ned Martin on NBC’s radio called the play:

“The 1–0 delivery to Fisk. He swings. Long drive! Left field! If it stays fair, it's gone! Home run! The Red Sox win! And the series is tied, three games apiece!”

Americans in the autumn of 1975 found themselves deeply divided. The Vietnam War had just come to an end, and the country was reeling from the Watergate scandal, political violence and inflation. Wages lagged, families stretched their paychecks, and new college grads struggled to find good jobs, wondering if the old American playbook still worked.

Baseball, once the national pastime, had become an afterthought. Football — faster, flashier and more TV-friendly — was king.

But then came Game 6. Fenway lit up like the gem of a ballpark it is and baseball reclaimed center stage, at least for a fleeting moment.

In the crowd at Fenway that night was baseball writer Roger Angell, famous for capturing the game from a fan’s perspective. He immortalized the moment in The New Yorker with his essay “Agincourt and After: An epochal World Series, reviewed.”

Roger Angell at his office in April 2006. (Mary Altaffer/AP)

To mark the 50th anniversary of Fisk’s walk-off home run, GBH News asked The New Yorker’s current editor, David Remnick, to read part of Angell’s essay:

I was watching the ball, of course, so I missed what everyone on television saw—Fisk waving wildly, weaving and writhing and gyrating along the first-base line, as he wished the ball fair, forced it fair with his entire body. He circled the bases in triumph, in sudden company with several hundred fans, and jumped on home plate with both feet, and John Kiley, the Fenway Park organist, played Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus,” fortissimo, and then followed with other appropriately exuberant classical selections, and for the second time that evening I suddenly remembered all my old absent and distant Sox-afflicted friends (and all the other Red Sox fans, all over New England), and I thought of them—in Brookline, Mass., and Brooklin, Maine; in Beverly Farms and Mashpee and Presque Isle and North Conway and Damariscotta; in Pomfret, Connecticut, and Pomfret, Vermont; in Wayland and Providence and Revere and Nashua, and in both the Concords and all four Manchesters; and in Raymond, New Hampshire (where Carlton Fisk lives), and Bellows Falls, Vermont (where Carlton Fisk was born), and I saw all of them dancing and shouting and kissing and leaping about like the fans at Fenway—jumping up and down in their bedrooms and kitchens and living rooms, and in bars and trailers, and even in some boats here and there, I suppose, and on backcountry roads (a lone driver getting the news over the radio and blowing his horn over and over, and finally pulling up and getting out and leaping up and down on the cold macadam, yelling into the night), and all of them, for once at least, utterly joyful and believing in that joy—alight with it.

It should be added, of course, that very much the same sort of celebration probably took place the following night in the midlands towns and vicinities of the Reds’ supporters—in Otterbein and Scioto; in Frankfort, Sardinia, and Summer Shade; in Zanesville and Louisville and Akron and French Lick and Loveland. I am not enough of a social geographer to know if the faith of the Red Sox fan is deeper or hardier than that of a Reds rooter (although I secretly believe that it may be, because of his longer and more bitter disappointments down the years). What I do know is that this belonging and caring is what our games are all about; this is what we come for. It is foolish and childish, on the face of it, to affiliate ourselves with anything so insignificant and patently contrived and commercially exploitative as a professional sports team, and the amused superiority and icy scorn that the non-fan directs at the sports nut (I know this look—I know it by heart) is understandable and almost unanswerable. Almost. What is left out of this calculation, it seems to me, is the business of caring—caring deeply and passionately, really caring—which is a capacity or an emotion that has almost gone out of our lives. And so it seems possible that we have come to a time when it no longer matters so much what the caring is about, how frail or foolish is the object of that concern, as long as the feeling itself can be saved. Naïveté—the infantile and ignoble joy that sends a grown man or woman to dancing and shouting with joy in the middle of the night over the haphazardous flight of a distant ball—seems a small price to pay for such a gift.Roger Angell, "Agincourt and After: An epochal World Series, reviewed"

Game 6 rekindled passion for baseball in Boston and across the country.

The very next night, Oct. 22, 1975, more than 75 million people watched Game 7 — the largest TV audience for any U.S. sporting event at that time.

The Sox jumped out to an early lead, but the Reds clawed back and scored the go-ahead run in the ninth.

Boston fans had to wait nearly three more decades before the Sox finally won it all.

Special thanks to the Estate of Roger Angell and the author’s granddaughter Laura Engel for the permission to feature his essay. Thanks also to David Remnick and David Krasnow at The New Yorker for playing ball.