STATE HOUSE, BOSTON, NOV. 4, 2019....Beacon Hill leaders reiterated a single statistic several times over the course of debate on a bill requiring greater financial transparency from the higher education world: over the past five years, 18 private colleges and universities in Massachusetts have closed or merged.

But those schools were not alone in facing challenges. Many of the key pressures that pushed them under — fewer available students and more competition to enroll them — present similar challenges to the University of Massachusetts, state university and community college systems.

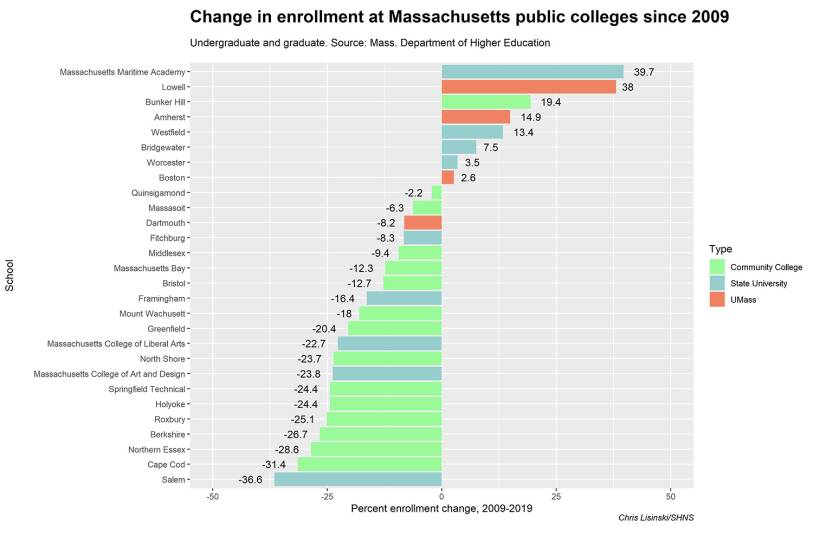

Over the past decade, 18 of the state's 28 public colleges and universities have experienced a decline in undergraduate student enrollment, half of which have seen drops of at least 20 percent. The change is more pronounced when combining undergraduate and graduate students, where 20 campuses now have smaller student bodies.

Schools have responded by tightening belts and cutting costs by combining back-end work such as IT and human resources. Many have shifted to greater use of adjuncts instead of full-time faculty. Northern Essex Community College closed 11 different academic programs over a single year.

But shutting down campuses, the most dramatic option that has prompted legislative action and pushed families to ask questions about stability they had never before raised, remains an unlikely outcome in the public sector, higher education officials say.

"I never say never because you don't know what the circumstances might be," Higher Education Commissioner Carlos Santiago said in an interview. "But I say, 'look, quite honestly, we think we can get the institutions to work together to keep costs down so students can keep attending.'"

Small-scale consolidation on a voluntary basis, he said, has "worked so far."

Across the country, college enrollment has been in a steady decline for about eight years at both private and public institutions, according to annual Census estimates.

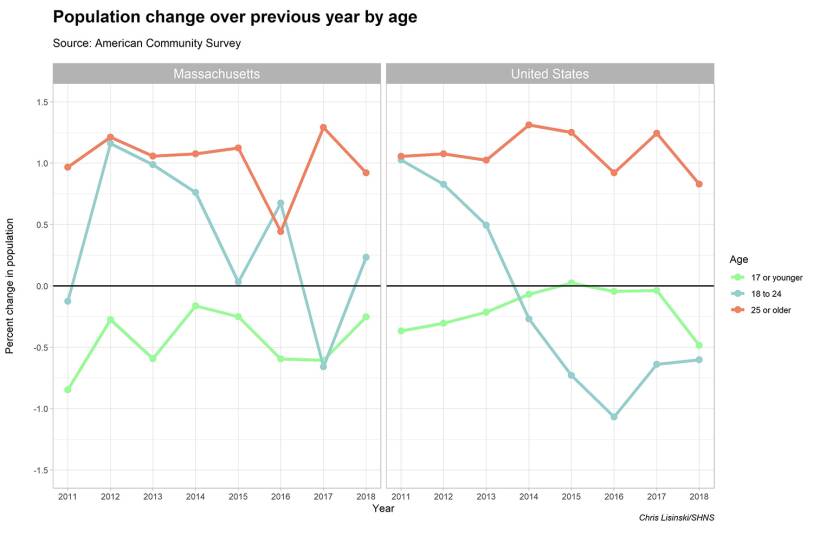

Experts say the trend largely mirrors macro-level demographic changes: fewer students are enrolling because there are simply fewer young people to enroll.

The U.S. population is aging, with older adults forming a larger and larger portion. On the other end of the scale, thanks to a combination of factors including parents more frequently delaying the age at which they have their first child and economic stressors during the Great Recession, the birth rate continues to drop, hitting a 32-year low in 2018.

As a result, the number of current and future traditionally college-aged youth is shrinking.

The trends vary by region and by ethnicity, but they have been sharpest in the Northeast. Since 2011, the population 25 and older in Massachusetts has growth at similar annual rates to the rest of the country, but the youngest age cohort has seen more pronounced declines.

In fact, the 17-and-under population in Massachusetts declined every single year for at least eight years, dropping by half a percentage point or more four times in that span — a sign that the strain will not let up for at least another decade. And because fewer students means fewer tuition checks to go around, declining enrollment creates budget headaches.

"This is going to continue until 2030 or 2032, so this is a long-term decline, which is putting institutions, nonprofits, public institutions in greater financial jeopardy," Santiago said.

Community colleges in Massachusetts have been most affected by declining enrollment. Every community college except Bunker Hill has fewer students today than it did in 2009, according to annual figures provided by the state Department of Higher Education.

Combined undergraduate and graduate student populations also shrunk at five out of nine state universities and one out of four UMass campuses over the same span.

That trend reflects a second large-scale factor: more than any other segment of higher education, officials say, community colleges typically grow and contract in the opposite direction of the economy. When unemployment is high, more people enroll to develop new skills or wait for an upturn, and when job openings are common, fewer are interested in pursuing school.

Both the country and Massachusetts have been in a strong economic stretch for years, with unemployment falling fairly steadily since the post-Great Recession peak in 2009. Although experts forecast little growth in the state economy because of labor capacity limits, the state's unemployment rate has stayed below 4 percent for three-and-a-half years.

"We're kind of used to this roller coaster effect of the economy on the enrollment," said William Heineman, vice president of academic and student affairs at Northern Essex Community College. "Even though we don't like it that our enrollment is down, it's not any cause for panic here because, basically, it was completely predictable based on what happened in the past. We expect when the economy does go sour again, we'll get that surge of enrollment again."

To cope with the changes, Northern Essex started closing 11 different academic programs in 2017, though officials waited until already-enrolled students finished to shutter any section, Heneman said.

No public school in Massachusetts has been hit as hard as Salem State University, which enrolled a third fewer students this fall than it did 10 years ago. The bulk of that decline has been from graduate programs, though the undergraduate side — which depends in part on transfers from community colleges — has dropped about 1,400 students over the past five years.

"There have been some ebbs and flows in terms of the number of high school graduates over time, but we have not seen a decrease of this magnitude in decades," said Scott James, the school's executive vice president in charge of enrollment management.

Salem State officials rolled out a voluntary separation program over the summer to blunt the impact and scale back operations to mirror a shrinking student body. James said 82 workers, representing every department, agreed to cuts that will save about $6.7 million per year. About 30 percent of that salary funding could be re-invested in new hiring under a provision in the agreement, he said.

Public institutions can find themselves alternating between two unenviable situations, too. If the economy does falter, more people may turn toward higher education and boost revenue from tuition, but the state could also scale back annual appropriations that are a significant factor in campus budgets.

Students and parents have taken notice of the trend lines, spooked by the sometimes sudden announcements, like that by Mount Ida College in April 2018, of private college shutdowns.

Bonnie Galinski, Salem State's associate vice president for enrollment management, said families visiting the school have begun asking about the institution's financial health in recent years.

"It is brand new," she said. "I've been in the industry a long time, and it is a brand new question that has just surfaced."

School officials stressed that, although a bill making its way through the House and Senate pitched as a response to school closures requires additional training and transparency, similar effects on public campuses are less likely than at private schools.

The state Legislature would most likely need to vote to close or combine schools because each one is named by statute and funded by government appropriations. Because of that, financial information is typically transparent, so warning signs could be clearer.

All factors considered, Santiago said, the trend in smaller liberal arts schools does not predict similar effects on public campuses.

"Our public institutions are different because they're not owners of land or building or resources. They belong to the state," Santiago said. "While a private institution can sell land or buildings, a public institution can't do that because they don't belong to those institutions."

But as demographic changes continue to unfold, other states have taken that step.

In Wisconsin, 13 two-year colleges will merge with seven four-year colleges, according to the Wisconsin State Journal. Similar, smaller-scale changes are underway in Georgia and Alabama and being weighed in Connecticut.

"It's more likely that further private closures are likely before the Commonwealth would be pressed into a position of having to consolidate or close the public campuses," Scott said. "But anything is possible in politics."