At the end of the album version of Wu-Tang Clan’s “Can It Be All So Simple,” RZA’s grimy, chest-rattling beat fades into an early-90s radio review featuring Clan members Raekwon and Method Man. They’re explaining the “why” behind the Shaolin crew’s colorful monikers, and as he explains GZA’s genius, Method Man likens the complete Wu-Tang to Voltron. You know, this thing:

It’s that veritable 1980s cartoon super-bot made of smaller bots; a mech-amalgam with its individual members coming together to form a powerful whole greater than the sum of its parts.

While they’re already powerful and well-respected enough individually, their cohesion into one being seems an inevitability. Their connection saves the day.

This brief moment local radio captured on a 1993 LP was at the front of mind as I listened to an entirely different album released some 18 years later: Uneasy, the pandemic drop from pianist Vijay Iyer. Or rather, it’s Vijay Iyer plus bassist Linda May Han Oh plus percussionist Tyshawn Sorey — each of these musicians shares in the labor equally and is credited as such. Individually, the members of this trio harness the vibrations of their sound machines with the deftest of touches and command a great deal of respect from the artistic community; as leaders they seem more then well-equipped to take on even the most grueling musical challenges. But here they combine their forces and form their own Voltron.

They operate in similar orbits — for starters, Iyer and Sorey are both Genius Grant recipients. Oh, with her two bandmates,numbers among faculty for Banff International Workshop in Jazz & Creative Music. For me, their presence seems personal: Oh was the first bassist I saw perform live in New York; Iyer’s music was present on the monitor speakers where I worked as a student programmer/DJ at WKCR in New York, and on at least one Das Racist mixtape that I kept in heavy rotation. Sorey and I never crossed paths as closely, but I was confused for him twice in three days by the same woman at two different venues (she wasn’t too keen on my observation that all Black people, in fact, do not look alike). Given this level of orbit, the fact that it’s taken them this long to record together, officially at least, feels like a mere delay of the inevitable.

Uneasy opens with “Children of Flint,” a title referencing the half-decade long public water crisis that consumed the Michigan city. Oh gets a solo from the jump — those low-wave vibrations rebound off your frame; some make their way into you. Depending on the speakers you use, it may even take on a quality reminiscent of the music Redman says goes “ba-BUMP” and “make[s] ya speakers pop.”

From the start, you can describe this as a tactile album — you feel Oh’s bass just as you feel the grounding lurch of Iyer’s left hand and crisp thwacks calculated in Sorey’s mind and executed by a self-assured wrist. Sometimes you feel familiarity -- as with the looping figure in “Drummer’s Song” (or an attachment to the Geri Allen original), or the subtle but no-less steady drone of “Touba”. But sometimes, you also feel the urgency. This is an album of then and an album of now; some things, after all — never for better and always for worse — do not change. You could say that this life is uneasy.

Case in point: “Combat Breathing.” Here we find our interlocutors engaged in a driving, throbbing musical dialogue. Iyer’s persistent chordal figures loom large over the affair like a set of thrice-tolling bells occasionally suspending us in time. Iyer initially wrote this in 2014 with the action of Black Lives Matter in mind, but it is contextually too at home in 2021 as a meditation on the murderous manifestation of police violence: a short while ago Derek Chauvin was just convicted on three counts for the murder of George Floyd a year earlier. If you didn’t know the when of “Combat Breathing,” no one would blame you for thinking it was a recent creation.

As the Modern Plague (and the preservation of ego and willful ignorance that follows) has demonstrated, these crises abound. Life doesn’t come at you fast as much as it just shows up when it pleases. Take the circumstances of this particular group, fated (maybe) to join forces and record an album that I’ll (definitely) be listening to. Iyer and Sorey and Oh are no strangers to one another in a collaborative context; the former duo linked up as early as 2003’s Blood Sutra and as recently as 2017’s Far From Over.

As told to Nate Chinen, in an interview aired on NPR, Iyer identifies the group’s birth at The Jazz Standard in June 2019. Like many of us, Iyer was caught up in the rapturous thrum of possibilities that defined that Summer: the Last Summer full of the thrills and promises and potentialities that could only come before the dawning of a new, fresh baked decade. By the end of the summer they were discussing the possibility of a record. In late 2019 they did it. And then 2020.

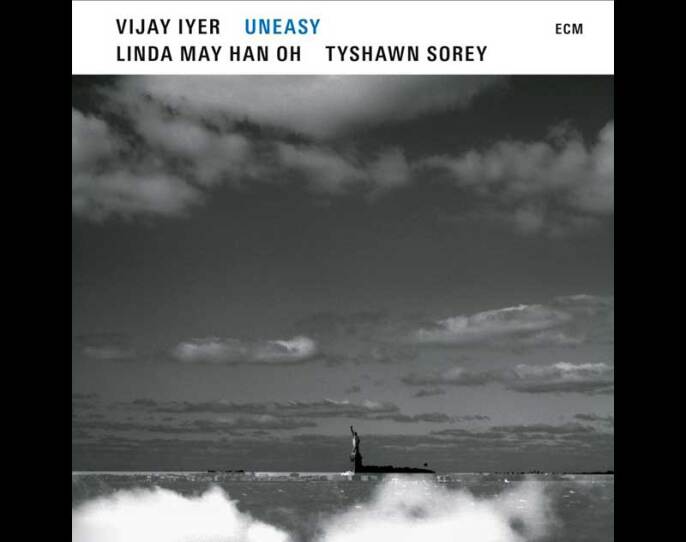

It’s hard to look at the album art for Uneasy — the Statue of Liberty, standing in the nocturnal solitude of Upper New York Bay — and not place it among the all too familiar images of deserted streets and dead parks and people-gutted buildings. Think for a beat, and you may find yourself longing for “normal” of bustling boulevards and fully occupied green space.

But think for two beats, especially after listening to this set, and you’ll realize just how precarious those before times were. It’s always been uneasy. And it’ll probably stay that way, until we can form a voltron that can administer justice to those forces that make this life so damn hard in the first place.

Check back later this week for a talk with Iyer on his thoughts about this review and whatever else may be percolating in his mind.