Boston’s City Council Wednesday unanimously approved a symbolic order to “acknowledge, condemn and apologize” for the city’s role in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. The resolution marks a new recognition of slavery’s impact within the community known as the nation’s “cradle of democracy.”

“Apologizing for a fundamental crime of enslavement of African people puts us in a position to begin to create a more fair and equitable city,” said the measure’s sponsor, Roxbury Councilor Tania Fernandes Anderson, to reporters before the council meeting.

More Politics

In addition to a “deep and sincere” apology, Wednesday’s resolution contains a four-pronged commitment: to remove anti-Black symbols and erect those that reflect repair and reconciliation, to educate Bostonians about the impact of slavery in the city, to create a “truth and reconciliation” registry for those looking for opportunities to express regret and to make policies that reverse harms done to Black Americans via systemic racism “in various realms of city life including housing, healthcare, education, and the workplace.”

The resolution does not carry the weight of law and does not provide funding, but Fernandes Anderson argued the formal apology sets the stage for a potential commission to study how Boston can implement reparations for slavery. The council, which has a majority of people of color, will soon deliberate creating that commission.

Fernandes Anderson indicated she is uncertain if there are enough votes to create the commission.

“We all campaigned,” she said, pointing to the election themes of equity and social justice on the campaign trail. “Some of us mean it, some of us want to do it but don’t have the courage, and some of us have the courage but can’t or are blocked. ... I’m not going to judge anyone,” she continued, referring to those who might ultimately oppose the commission for fear of retribution from constituents.

“Maybe today, they’re not ready. Maybe tomorrow, they will be ready. I’m not going to judge you for that, but I will speak truth, God willing,” Fernandes Anderson told reporters.

As the resolution came to the council floor, long-time Dorchester Councilor Frank Baker, who is white, said he would support the measure despite a personal struggle with the apology.

“Acknowledge and condemn, I’m all in. Apologize, I’m a little uneasy about, if we can be honest,” he said, pointing to his own experience growing up poor. “I feel so far removed from John Winthrop and Peter Faneuil and Harvard University ... so the apologize part is difficult for me, but I think if my words can help your community heal and our community in Boston heal, then I’m absolutely ready to do this.”

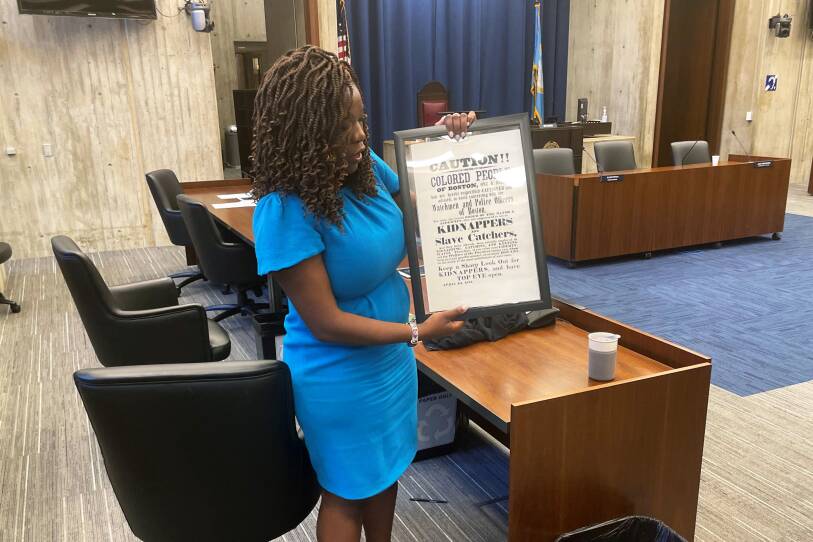

In her remarks, co-sponsor Councilor Ruthzee Louijeune held up a framed copy of a now-famous poster created by abolitionist Theodore Parker. It warned free Blacks of a “recent order of the mayor and aldermen” that empowered “watchmen” and Boston Police officers to act as slave catchers to enforce the federal Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.