In 1903, a 10,000-year-old skeleton was discovered in a cave in Cheddar Gorge in Somerset, England. He was immediately baptized "Cheddar Man," and curiosity began to swirl about what one of the earliest known Britons might have looked like. Early interpretations pictured him with pale skin, a mustache and rosy cheeks.

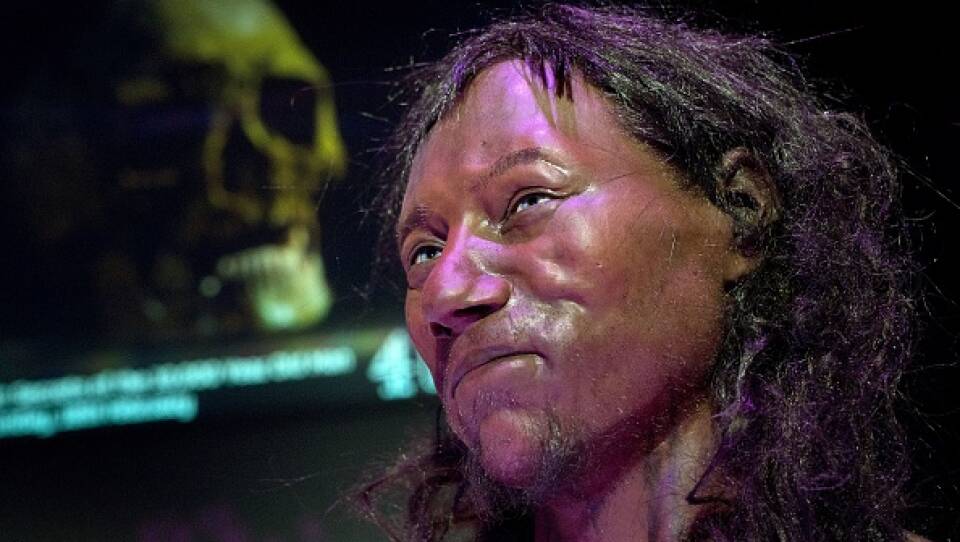

But last year, through the revolutionary technology of genome sequencing, scientists revealed what they believed to be a more accurate reconstruction of Cheddar Man. Yes, he had blue eyes, and sure, he may have sported a mustache, but it was also very likely he was dark-skinned with curly black hair.

While scientists were not surprised by this discovery — several other skeletons of early hunter-gatherers found across Europe also appear to have had dark skin and light eyes — it astonished much of the British public. But Angela Saini, a science journalist and author of “Superior: The Return of Race Science,” was not surprised by the revelation.

“In the past, we didn’t look the way we do now. There was always migration and churn, with people coming in and moving,” said Saini. “This idea that there were some pure groups of people that looked the same, and that somehow over time it got muddied ... It was being muddied from the beginning. We were always muddy as a species."

In her book, Saini details the history of how science has been used to justify racial policies and prejudices as being rational and objective. “Race is really just a pawn in this game," she said. "It’s a tool. It feels scientific. It’s a way to make what are essentially political arguments sound like intellectual arguments."

Many notions about race took off during the Enlightenment, when scientific classification schemes — just about everything from mushrooms to bears — took off. Simultaneously, growing European empires seemed to legitimate a push towards codifying racial hierarchies. Even Charles Darwin, who with his pioneering work on evolution stressed that we had one common ancestor, fell prey to the idea that there was a natural racial hierarchy within the human species. Though Darwin was a strong abolitionist himself, he could not divorce himself from the political discourse of his time.

While racial bias in mainstream science is strongly frowned upon now, Saini does not believe we should do away with racial categories completely. “I think it’s right we shouldn’t think [about race] biologically, but race was made real through overuse, politics, slavery, genocide, colonialism and other horrible, horrific things done in the name of these superior and inferior categories. And we live with the consequences of that now,” Saini argues. Until society is able to reconcile with the damaging legacy of these ideas, Saini believes we cannot get rid of these categories, socially and politically, to address the rights of minorities and right historical wrongs.

But she also worries that with a new wave of global, nationalist rhetoric, race science, which now exists on the fringes of academia, might make a comeback in public discourse. “I really hope we come out of this better, that society somehow forges a more enlightened path, and educates itself about the history and doesn’t repeat the same mistakes,” Saini said.