Millions of people walk Boston’s Freedom Trail every year, the red brick path that connects 16 historic sites central to early colonial history and the American Revolution.

But there has been no monument to recognize Boston’s connection to slavery — until now. On Sunday, King’s Chapel on Tremont Street, one of the Freedom Trail’s sites, will unveil a memorial statue to honor 219 people who were enslaved by members and ministers of the church.

Installing such a prominent 14-foot-tall statue of a Black woman releasing six birds out of a cage to freedom is historic and “revolutionary,” local historians say.

“One of the things that really excites me about this memorial is the fact that it is on the Freedom Trail and that there will be this humongous, large Black woman at one of the busiest corners in Boston that people will have to walk by and see,” said Roeshana Moore-Evans, the strategic advisor for the church’s committee that has overseen the memorial project. “They’ll want to know more.”

Artist Harmonia Rosales designed the memorial in partnership with MASS Design Group. The group also worked on the Embrace Statue on Boston Common.

“King’s Chapel broadly reflects the foundation and contradictions of America as a whole,” Rosales said.

“I wanted people to stop in awe, not just stop in curiosity, but see her beauty in complete natural form,” Rosales said. “I want people to have a sense of just being seen.”

Staff at the church hope the new memorial will invite anyone who visits or walks the Freedom Trail to think more about institutions that wouldn’t have been possible without the slave trade. Slavery was deeply embedded in the economy of Boston and early New England, and Moore-Evans says this memorial is a step toward education and healing.

“When people think about slavery here in Boston, they think that ‘up here’ wasn’t as rough. But they don’t realize that there were actually slave owners who had plantations in the Caribbean,” she said.

The unveiling in Boston comes at a moment when cultural institutions, like the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and Boston’s Museum of African American History, are facing pressure from the Trump administration to roll back programs focused on Black history.

“Faith institutions and hopefully other institutions will start to be bold and courageous about telling the truth about who we are as a country,” Moore-Evans said.

“Boston’s history was replete with complicity … with slavery."Rev. Joy Fallon, the church’s senior minister

A deeply complex history

The memorial is part of a larger project, which began in 2017, to reckon with the church’s ties to slavery. The church hired its own historian, who discovered the identities of the 219 enslaved people by combing through wills as well baptism, marriage and burial records.

King’s Chapel’s ties to slavery may surprise people. “Slavery was legal in all 13 colonies,” said Dean Denniston, the chair of the memorial committee. “But it was never talked about, especially here.”

King’s Chapel was the first Anglican church in New England when it was founded in 1686 and later became the first Unitarian church in the United States.

“Regularly, members of this congregation during the colonial period, when they passed on things to their family, they would pass on a bureau and a cow and a human being,” said the Rev. Joy Fallon, the church’s senior minister. “So that helped us begin to identify the number of enslaved people.”

Many of the early worshippers were business leaders, like Charles Apthorp, a wealthy merchant and slave trader. He used his wealth to help the church grow. A memorial to him still hangs inside the church, while the Apthorp family is buried in the crypt below.

Even after slavery was abolished in the state in the late 1700s, Massachusetts continued to profit from the slave trade. Cities like Lowell benefited from the cotton and new technology produced by slave states.

“Boston’s history was replete with complicity ... with slavery,” Fallon said. “Our whole port had grown up and been successful because of this whole trade.”

The Georgian-style church has one of the best-preserved colonial interiors in Boston, with a “floating” pulpit and upholstered pews, which wealthy families used to buy. In the once-segregated space, Black people worshiped in the upper galleries.

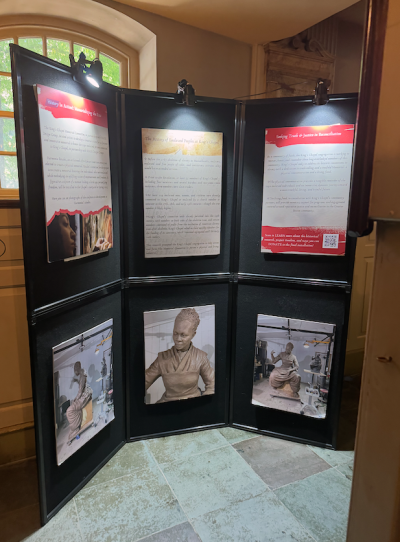

Today, poster boards throughout the space acknowledge that history.

Fallon cast her church’s changes in contrast with the federal government’s effort to avoid discussion of slavery at America’s government-run historic sites. The congregation itself voted to approve the $2 million memorial project.

“The congregation votes on everything,” Fallon said. “There also is the fact that as a church, what do we have to fear? We, if we’re trusting in God, then what do have to fear?”

“I felt, because we’re on the Freedom Trail, we had a special moral obligation ... a moral obligation to tell the truth,” she said.

A new opportunity for tour companies

Many of the companies who offer tours on the Freedom Trail are already thinking about how to present Boston’s diverse history.

Leah Sause, a historian and outreach director at Hub Town Tours, says the new statue will encourage all tour guides to address the “complex” history that touches on race and gender.

“You can’t ignore this statue. And I think that is super important,” she said. “This woman being on a pedestal, I really appreciate. She is given the same treatment as the Samuel Adams statue in front of Faneuil Hall.”

Downtown Boston offers plenty of opportunities to educate about slavery, but a physical representation will put it in front of people’s faces in a new way, she says.

“You can talk about slavery when you’re at John Hancock’s headstone, because there is a headstone next to him: Frank. He has no last name and he’s listed as a ‘servant.’ We’ve always believed he was enslaved,” Sause said.

“So that is a gateway into talking about complex histories and kind of layers to the revolutionary story,” she continued. “But something so striking like this [statue] — it’s the first of its kind.”

Sause estimates that only about 3% to 7% of statues in Boston are women, and less than a handful are of Black women. She hopes the new memorial inspires more to shed light on less-told parts of history.

“Ten percent of Boston was enslaved during the American Revolution,” she said. “So that is not a part of the story you should ignore.”

Why now?

The statue is part of a longer project at King’s Chapel about slavery that will include public lectures and events.

A special service on Sunday to unveil the memorial will include musical performances and a reading of all 219 names.

“We can’t change the past, but we can tell the truth about it,” Fallon said.