Boston Mayor Michelle Wu has declared a heat emergency lasting until Friday. So, it might be a little cruel to bring you a story from the North Pole, but we hope contemplating a cooler place might bring you some comfort. While we’re melting away in this heat wave, there are some people in that region conducting important research and expanding our scientific knowledge.

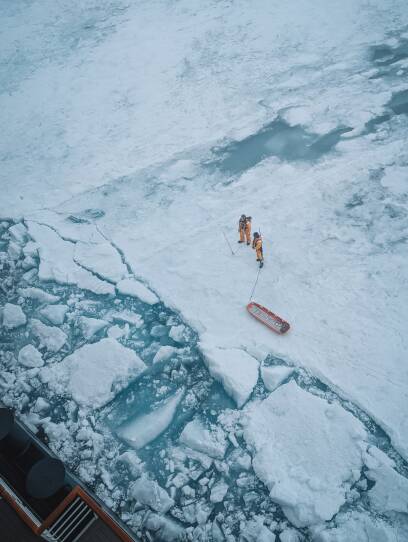

That includes Dr. Luke Apisa. He’s a clinical instructor of emergency medicine at Harvard and a faculty member of Mass General Brigham’s Division of Space, Ecological, Arctic and Resource-Limited Medicine — or SPEAR MED, for short. He and his team are currently in the Arctic aboard an icebreaker ship.

Apisa joined GBH’s All Things Considered host Arun Rath to share more about what the SPEAR MED team is doing at the North Pole. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of their conversation.

Arun Rath: Could you tell us what exactly you are doing out in the North Pole? What specific research projects are you working on?

Dr. Luke Apisa: I appreciate the question. This is actually not a research trip, but a medical support trip. I work in the division of SPEAR MED, and we’re here supporting a team of runners who were looking to run a marathon at the North Pole.

We have a forum on the way up called the North Pole Forum, which is a team of experts — some from the Harvard Kennedy School’s Arctic Initiative, others from Norway, Denmark and around the world — talking to the runners on the way up about issues of the climate.

So, less research focus on this trip, and more outreach to the public and keeping people safe while doing things in extreme places.

Rath: Let’s talk about that in more detail, because that is fascinating. For health in extreme environments — I mean, you’re talking about space, and then the Arctic. Tell us what that involves.

Apisa: We like to say that the work we do is medicine anywhere outside the four walls of the hospital. You know, medicine looks a whole lot different when we’re suddenly taken away from all of our fancy toys and technology, when we’re out in the field on the side of a mountain in the Himalayas, or certainly when we are caring for astronauts in space.

And it’s no different here in the Arctic. You have to work much differently than you do back in the hospital, and do a whole lot more with a whole lot less. We’ve got a backpack and a duffel bag, and that’s our entire medical kit for the three weeks we’re out here. Anything we need to do to help someone if something goes awry has to be within that small kit we carry.

Rath: What are the kinds of situations that you would face in the Arctic?

Apisa: It was a whole range of things you might imagine to happen in a marathon in Boston, let’s say, right? We have these people out there exerting themselves on the ice to very extreme degrees. We can see heart attacks and cardiac issues that might come up in the Boston Marathon that we work every year. We have these runners running in extreme cold, so frostbite and hypothermia are certainly other factors that we worry about.

And lastly, orthopedic injuries. The last year that this race was done, we unfortunately had a patient break their wrist from falling on the ice. And the runners, when they ran with us just a few days ago, were in quite slushy conditions. That’s a whole separate story. Certainly, we should not be expecting to see slushy ice at the North Pole, and that was a huge risk for the runners in terms of slip-and-fall risk.

Thankfully, everyone did well this go-around, and we had no major issues from the orthopedic side.

Rath: Is that slushy ice one of the indicators of the warming that we’ve been talking about?

Apisa: Yeah, undeniably. If you look at the Arctic ice over the last 50 years that it’s been monitored, we’ve seen a shrinkage of almost 40% since the late 1970s. There have been some phenomenal Arctic researchers who talked about that in a lot of depth on the trip up.

The Arctic ice is sea ice, so you can imagine these multi-thousand-ton sheets of ice smashing into each other and forming these huge ridges. We don’t see that anymore. I’m looking outside my window now, actually, at the polar ice cap, and it’s almost perfectly flat. In large part, that’s due to the thinning we’ve been seeing as that ice has been melting.

When we ran the race, we were right around freezing, and as the sun came out midway through the race, just a couple of hours in, it started to bake the top of the ice. By the end, the runners were running in slush with pools of water around them. The North Pole just shouldn’t look that way.

Rath: You said, “We.” Did you run the marathon yourself?

Apisa: I wish! No, those of us working medical aren’t able to, so I was sadly standing on the sidelines, watching them have all the fun.

Rath: Tell us more about this team and what the marathon was like.

Apisa: I’ll say the North Pole Marathon Group is phenomenal. It’s a company called Runbuk. They also do another marathon [that] we supported them medically for earlier in the year, called the World Marathon Challenge, in which a team of runners run seven marathons on seven continents in seven days.

These are people dedicated to doing pretty extraordinary things in pretty extreme places. One of the runners I should shout out, particularly, is Becca Pizzi. She’s a Boston local, and she set the world record this year for the fastest woman to run a marathon on the North Pole.

Rath: And what was that time?

Apisa: That time was four hours and, I believe, 46 minutes to set the world record this year, beating the record that was previously set in 2014 of four hours and 52 minutes.

Rath: Wow. Is that as wild and extreme as it sounds to pull that off? That sounds wild.

Apisa: It is every bit as wild and every bit as extreme as it sounds. Becca is an extraordinary runner, and she had a lot of grit to make that time.

Rath: Do you learn things from this kind of event that will then be applicable to running in other situations? What are the kinds of things you learn in a situation like this?

Apisa: We like to say in our fellowship, “The human physiology is a bespoke solution to a bespoke set of conditions.” What we mean by that is the human organism has evolved to live here terrestrially, roughly at sea level and in a pretty tight band of temperature and pressure. When we start to push the human body to the edges of the environment that we’re used to living in, we really start to see how the underlying machinery works.

The research we do in the Himalayas, here in the Arctic, or on astronauts in space is really the key to helping us unlock some of those core aspects of the human organism to help us treat people better when we come back to the hospital in Boston.

Rath: That’s fascinating, because I’ve heard so much about how humans have evolved to basically be these fantastic endurance athletes, right? To take us out of the environment in which we evolved must be fascinating.

Apisa: It certainly is.

Rath: Now, we’re talking with you on … it’s a great internet connection. You sound fantastic. Has communication improved at the North Pole, or is it usually like this?

Apisa: Communication has certainly improved. We’re calling over a satellite internet connection through Starlink. This was just put on this icebreaker, which is an extraordinary vehicle — an icebreaker newly built just three years ago, quite modern technology. Starlink was just added to it around two years ago, so this kind of real-time connection here in these remote places is a profoundly new thing to be able to do.

It makes medical issues here at the poles easier to coordinate when it comes to rescue. You’re going out to this environment — it took us nearly five and a half days to reach the North Pole. Imagine if our communication back [to home base], we’re sending 160-character text messages. It would make coordinating a rescue, if needed, a whole lot more difficult.

Now, we can have video chats live, if need be, which makes things extraordinarily more safe for the runners here.

Rath: And we’re not even going to be your most long-distance call today, right?

Apisa: That’s right. Jonny Kim is an extraordinary human being. He was a Navy SEAL first. He ended up, then, going to Harvard Medical School, training for one year in the emergency medicine residency in Boston at the HAEMR [Harvard-Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency] program at Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham before he left because he had been accepted into the [NASA] Astronaut Corps.

Jonny’s on the International Space Station right now, and he’s actually going to be calling in about an hour here to talk to the residents about his experience as a doctor and an astronaut. We’ll be tuning in here from our icebreaker, heading its way back from the North Pole.