More than 7,000 people have died in Massachusetts from COVID-19. These lives lost are much more than a number — they're individuals with fascinating lives and people who loved them. We're remembering and sharing the stories of some of the people we have lost in a series titled "Lives Remembered."

When the coronavirus pandemic arrived in Massachusetts, Ari Seckler, 23, remembers talking to his siblings. They were worried the virus could take their grandparents, ages 94 and 95. They were right.

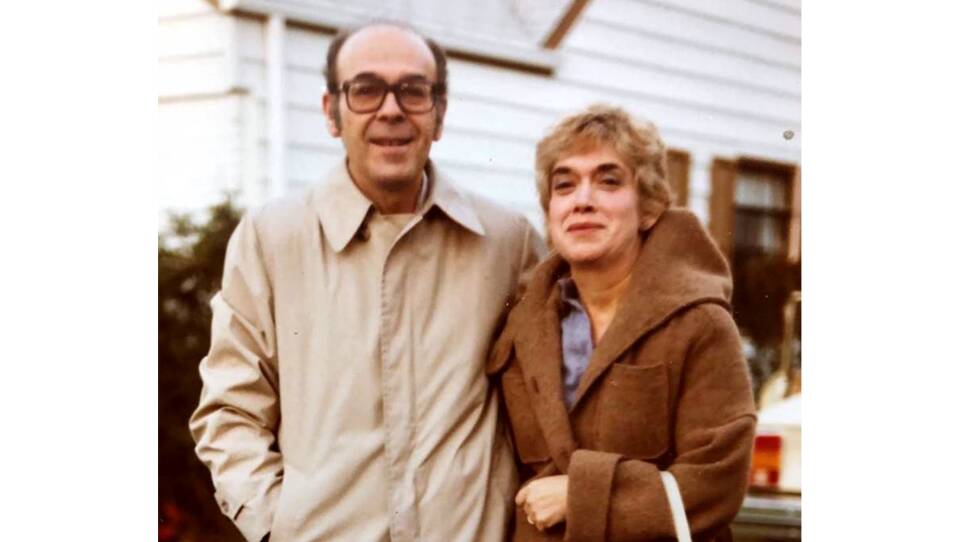

Married for 67 years, Evelyn and Bernie Seckler both died in April — within three days of each other — in an assisted living facility in Newton. They were among a population particularly hard hit by the virus; deaths in nursing homes and long-term care facilities account for about 60 percent of all COVID-19 deaths in Massachusetts.

Just as Evelyn and Bernie’s lives ended in parallel, they also began that way. Both were born in 1920s New York, in Eastern European immigrant communities — Evelyn on Manhattan's Lower East Side, Bernie in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Evelyn’s family owned a dry goods store; Bernie grew up making milkshakes behind the counter at his family’s candy shop.

“The candy store was really the center of socializing for a lot of people,” said Evelyn and Bernie’s son, Stephen Seckler. “His parents kept that store open like 20 hours a day.”

The couple married in 1953 and had two children, Judy and Stephen. For nearly 40 years, they lived in Great Neck, New York.

The Great Depression had hit when Evelyn and Bernie were still children. Despite the hard times, Evelyn became the first in her family to go to college. She eventually got a master’s degree and worked as a school psychologist. But still, the Depression shaped her worldview.

“She had strong opinions about not wasting money and then strong opinions about politics,” Stephen said. “She really believed in the role of government to help bring up people who were less advantaged.”

Thanks to this Depression-era mindset, Evelyn was also protective of her friends and family. Ari remembered that when he was leaving the house she would often say, “'Is that all you're gonna wear? You're not going to put on a thicker coat? You're gonna be freezing.’”

“She really was always thinking about the people around her, the people that she loved,” Ari said, “just making sure that the scary and not so good things about the world are kept away.”

In a memorial service on Zoom, Judy remembered her father as always striving. He was a math professor who was so committed to mastering the field that he learned Russian just to translate Russian math textbooks.

Bernie was similarly passionate about his hobbies outside of work, ranging from music and food to tennis and museums. And he had one passion that became almost legendary.

“Anybody who knew my father knows how fanatical he was about his stamp collection,” said Judy.

He had binders of stamps and particularly liked to collect stamps with art reproductions on them. He would spend hours researching art at the New York Public Library and he was actively involved in a group called Fine Arts Philatelists.

“If you were a family member or a friend and you were traveling overseas, you got a little assignment,” Judy recalled. The assignment was to bring back a stamp or, like when Judy went to the Palace of Versailles, a whole stamp catalogue.

“Every letter I got addressed to me from my grandparents — every birthday card, every letter at summer camp — there was sure to be a little note that said, ‘Make sure to keep the stamp,’” remembered Ari. It was to be returned to Bernie, for storage in one of his thick binders.

In 2009, Bernie and Evelyn moved to Massachusetts to be near their son and his family. And here, Stephen said, the couple grew closer.

“They had kind of a stormy relationship throughout a lot of their marriage,” he said. But in Massachusetts, “they were inseparable. They were just always with each other.”

Eventually, they moved to an assisted living facility, the Falls at Cordingly Dam in Newton, where they were in a unit for those with memory loss. Evelyn had begun suffering from vascular dementia and Bernie had recently had a fall. The couple needed more assistance and care.

That’s where they were when the coronavirus pandemic arrived.

For Ari and the couple's other grandchildren, this was their first experience with the death of a close relative. He said even though they knew their grandparents were vulnerable to the virus, it was especially hard to lose both at the same time.

“Despite the fact that we saw it coming, it was still obviously a very jarring, strange experience,” Ari said. “We didn't get to go through the normal goodbye process of sitting bedside.”

But the family also emphasized what they see as silver linings. Bernie and Evelyn both lived long, full lives. Because of the pandemic, the couple's older grandchildren were staying with their parents, so the family was together to mourn their loss. And memorial services via Zoom, though difficult in their own way, meant that more friends and family members could join to honor the couple's lives.

The most challenging time for Stephen was after his father died — he was worried about what it would be like for his mother. The family wasn’t able to visit because of worries about contagion, but a nurse helped arrange a call.

“We did get on the phone with my mother, who was not conscious, and we sang 'You Are My Sunshine,'” he said. “That was very hard.”

In recent years, Ari said, the family sang this song after meals together to bring life and liveliness to the gatherings. This time it marked the end of two lives.

Evelyn never regained consciousness and died three days after Bernie. Neither knew of the other’s death.