Massachusetts was once crisscrossed with railroad tracks that served as routes for freight and passengers. But many of those tracks have been dormant for generations, and more than 60 of them have been converted to bike paths. And while creating a bike trail might seem like one of the least controversial moves a town could make, a bike path is dividing one North Shore community.

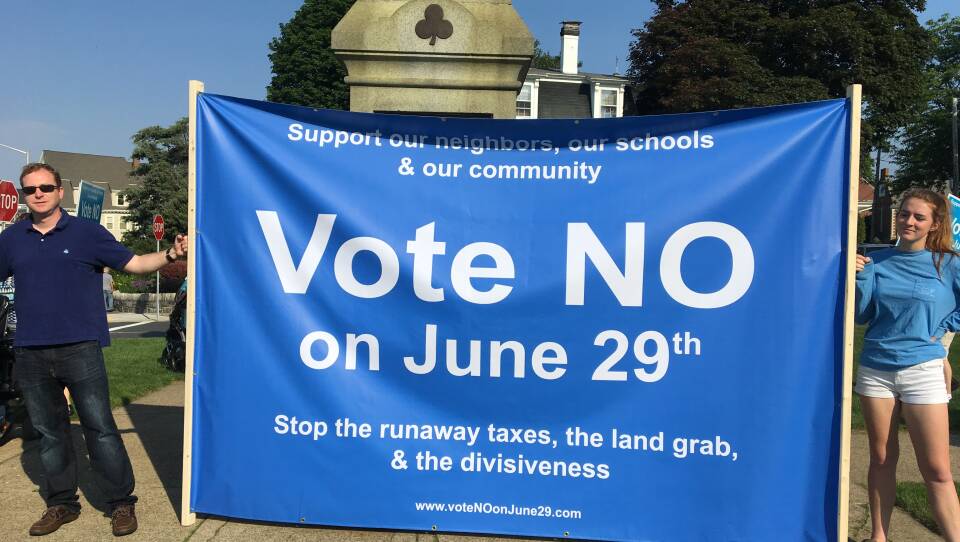

Standing on a traffic circle, with Swampscott Town Hall on one side and the rolling waves off Kings Beach on the other, about 15 people waved signs at passing traffic on a recent morning before work. The signs read:

“Vote ‘no’ on June 29. Stop the runaway taxes, the land grab, and the divisiveness.”

That divisiveness, Swampscott resident Paul Dwyer said, comes from a town plan to create a bike path.

“Their proposal, the yes people, is a definite violation of human rights,” Dwyer said.

That’s because Swampscott plans to seize land for the path using eminent domain. Swampscott resident Nancy Maloney says this has become a huge deal in town. “I’m like really frustrated that this is essentially pitting neighbor against neighbor,” she said.

That’s clear driving around Swampscott, where lawn after lawn is decorated with signs urging neighbors to vote YES or NO in a town referendum on the bike path next Thursday. Opponents also object to the expense of a rail trail. And they got enough signatures to force the town-wide vote — the first of its kind in town in about 40 years.

Maura Carroll is one of the Swampscott residents urging voters to reject the bike path. She walked across the lawn behind her house and points to where decades ago, there were railroad tracks. Now, it’s all grass, up to a line of trees where the mid-point of the new path would be. “The back of my yard, from my patio to the ten-foot wide path, which is what they first discussed taking, was 10-foot wide, would be about 47 feet,” she said.

Back when trains were going by, the railroad had an easement to use the land. The utility National Grid later took over the easement to run the power lines that are now overhead here. Carroll doesn’t pay taxes on that property. National Grid does.

“But paying taxes does not equate to land ownership,” Carroll said.

Carroll’s not alone. About 90 abutting landowners also could make a claim of ownership. The Swampscott Town Meeting had voted to study the ownership question moving forward, but Thursday’s referendum could put a stop to that.

Alexis Runstadler is leading the group that’s in favor of the path. “This process will identify whether or not those people own those properties," she said. "As of now they don’t, as far as the town knows and as far as anybody else knows.”

Runstadler's property also abuts the old railway, but the scene is totally different from Carroll’s yard. The bike trail would be hidden away, down a steep slope in the woods behind her house. "You can see it’s a utility corridor and it’s basically a pathway already,” she said as she looked down at it.

Runstadler used to live near a bike path in Fairbanks, Alaska, and said she loved it. “It will give us new open space," she added. "It will give us a two-mile linear park through the entire town, linking the train station. It links three of our schools. It’s something that everyone can enjoy.”

The roughly two-mile trail would connect to an existing one in neighboring Marblehead.

“Lynnfield has a trail, Topsfield has a trail, other communities are working on trail," Runstadler said. "This is a thing that people really want in their community.”

The town’s government wants it, too. Although Swampscott town administrator Sean Fitzgerald said using eminent domain to get it isn’t their first choice. The town, he added, would rather just work with the abutting landowners to take over the easement that National Grid has.

“If someone did not want to negotiate with the town, it would really create a very difficult process," Fitzgerald said. "I think with the authority to utilize eminent domain the town is able to move forward and accomplish what we’re setting out to do.”

And even if they do wind up taking the land, he says the town plans to work with the abutting landowners.

“We want the abutters to know that they’re going to be the town’s neighbors," Fitzgerald said. "And we want to make sure that along the rail trail, if we can design the trail in a way that makes sense for those neighborhoods, we will do that.”