Omar Mateen cemented his deranged message of revenge in blood, randomly selecting a popular Orlando nightclub that catered to young gay men. Mateen’s motive was later ascertained to be anger about the U.S. bombings of Middle East ISIS targets. In something of a blind rage, the 29-year-old shooter killed 49 people and wounded 53 at the Pulse nightclub. It was June 2016, Latin night at the club — mostly Latinos were killed in what is the deadliest attack in the history of violence against LGBTQ Americans.

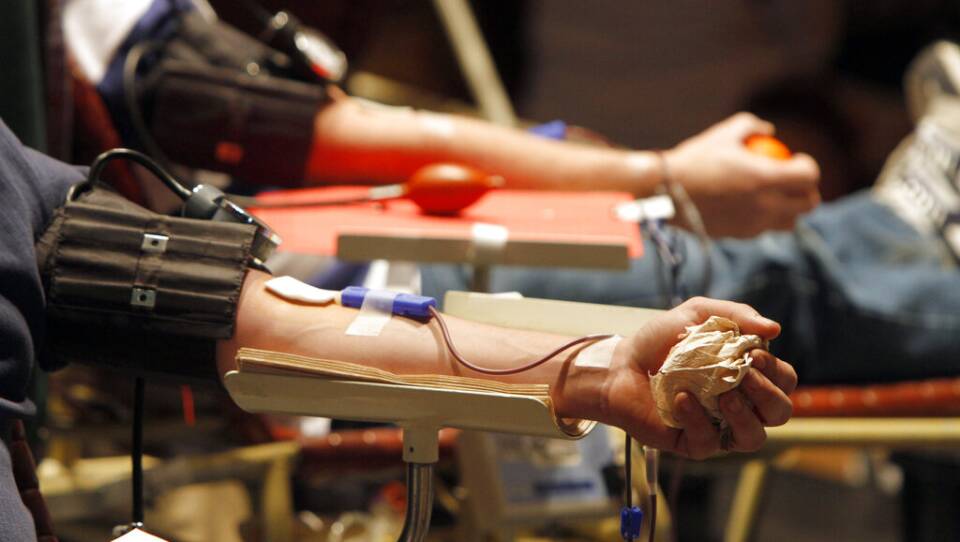

Orlando’s gay community, shocked by the murderous scene and grieving, turned out in huge numbers to donate blood. Lines of eager blood donors flocked to the OneBlood donation center, which had put out an immediate call for donors. Blood was urgently needed because of the huge numbers of people injured at the scene. But potential donors who were gay or bisexual were turned away. The Food and Drug Administration in 1983 instituted a lifetime ban against blood donations from gay men to protect recipients of blood transfusions from the chance of contracting HIV, the virus which causes AIDS.

The year before the Pulse tragedy, the FDA revoked that ban, but replaced it with another restriction. Gay men had to abstain from sex with another man for 12 months prior. LGBTQ advocate Jay Franzone was abstinent for a year in 2017 so he could donate blood. He told NBC News, “This is a crisis of the FDA’s own making.” Franzone and other advocates have long pressured the FDA to drop the 12-month restriction but have only been successful in forcing the agency to reduce it to 3 months.

Like a lot of others, I thought when the FDA lifted the ban, it cleared the way for gay and bisexual men to donate. Three months may be considered a more reasonable restriction, but as advocates point out, gay and bisexual men are the only group stigmatized as potentially having “bad blood.” That’s even though every unit of donated blood undergoes 13 tests, including for HIV.

It’s especially bad timing right now because the need for blood worldwide has soared as blood donations have plummeted. With blood supplies at their lowest levels in more than 10 years, the Red Cross declared recently — for the first time ever — a national blood crisis. Donations typically dip during the holidays, but the ongoing pandemic has kept potential donors away, despite the increasingly urgent calls from the agency. That means less blood for hospitals that need it for blood transfusions, and less for the Red Cross to use in emergencies.

UCLA’s Williams Institute estimates that by eliminating the restriction on gay men donating blood, overall donations could increase by as much as 600,000 more pints of blood a year. That would significantly ease the crisis that has left blood supplies are severely depleted.

In the wake of the national blood shortage, the White House is urging the FDA to remove the 90-day restriction, as are 22 U.S. Senators including openly gay Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin joined by openly gay U.S. House representatives Ritchie Torres of New York and Mark Takano of California. Other countries have already lifted the blood donation ban against gay and bisexual people; the United States feels out of step.

In June 2016, after the Pulse shooting, many of the Floridians who were prevented from donating pointed out a cruel reality: it was easier for a man like the Pulse nightclub shooter to purchase a gun than for a gay man to donate blood. This simply doesn’t make any sense.