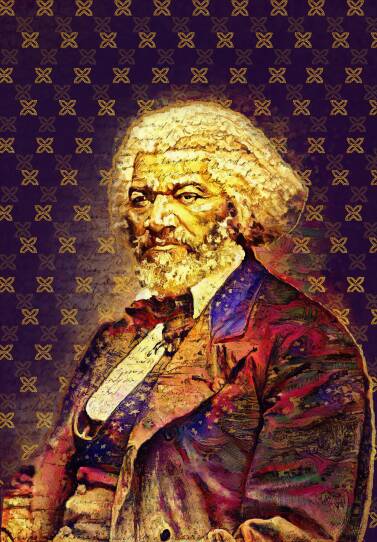

In 2021, the Boston Modern Orchestra Project (BMOP) launched a five-year initiative, “As Told By: History, Race, and Justice on the Opera Stage”, spotlighting Black composers and featuring five operas that showcase key Black figures in history. The second opera in the series, “Frederick Douglass”, by the late and prolific composer Ulysses Kay, centers on the abolitionist leader’s image, reputation, and life after the Civil War. This week marks the first time Frederick Douglass has been performed on stage since 1991.

Grammy Award-winning conductor and the founder and artistic director of both the Odyssey Opera and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Gil Rose, joined GBH’s All Things Considered host Arun Rath to discuss the project and the initiative. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of their conversation.

Arun Rath: So to start, tell us a bit more about the mission behind “As Told By”, this series, and how “Frederick Douglass” fits into it.

Gil Rose: We wanted to explore. In general, our mission is to explore pieces and operas that have somehow or for some reason disappeared from public view, maybe not because they deserve to disappear from public view, but for some other reasons it came and went and we try to bring them back and we tried to present them in performance, resurrect them, revive them as it were, and then we seek to make commercial recordings because that’s a great way for the world to know about it. And we released them on our record label BMOP/sound. And this is just part of that larger mission. However, it was a specific mission to also address some important operas by Black American composers that feature Black historical subjects. And, this was how we started. And this was the premise, and we built up this program, and this is now our second with “Frederick Douglass” by Ulysses Kay and Donald Dorr.

Rath: And this particular work was last performed in 1991, and it seems like, I don’t know if this is a pattern with Black composers, that the work gets performed in their lifetime and then falls out of the repertoire.

Rose: Well, I think this isn’t so much a race issue as sometimes operas suffer from, you know, putting on a premiere — world premiere of an opera is a complicated affair — and lots of them don’t go well. They don’t get a tryout, you know, like a Broadway tryout in Boston or New Haven. They have to go on the opera stage and they’ve fully realized and I think that premier of “Frederick Douglass” in 1991 at the New Jersey State Opera, which is no longer. It suffered from a couple, let’s say, tepid reviews, maybe even a little bit stronger adjectives could be used, but the opera just subsequently never garnered any other interest. When The New York Times doesn’t give you a very positive review, sometimes people aren’t willing to take a chance, and they aren’t going to do the work to look at the piece, and how can this be realized, or should it be realized? And that’s what we did with “Frederick Douglass”. We went back and found the materials which weren’t easily available. We had to research them at the New York Public Library and we decided it was an important opera and maybe had not had a good first outing and never got a chance at a second.

Rath: One would naturally think that the life of Frederick Douglass, that seems, wow, that certainly seems like operatic material. But this particular opera, though, it doesn’t cover, you know, the escape, the war. It’s later in Douglass’ life. Tell us about the trauma and the dramatic action that this takes us through.

Rose: Yeah, this is not, you know, you might see the title “Frederick Douglass” and think it’s sort of a biopic opera, you know, from cradle to grave, but it’s not. The opera focuses on the period after the Civil War and it’s a very human story. It’s not a story about political events, really. I mean, there is intrigue in the politics, but it’s really the story about the man. And its also the story of his wife, his second wife, who was white. So they had an interracial marriage at a time, which was a very rare thing, and he was a public figure, and the exploration is about how they interact in this world where there are plots against him and the relationship with his son by his first marriage is explored. So it’s a very personal and psychological opera, not so much dramatic events, but dramatic people.

Rath: Tell us a bit about Ulysses Kay, the composer.

Rose: Now, Ulysses Kay was one of those composers who, you know, nowadays people recognize the name because it’s a very specific name, too. It’s a great name, but you know he’s fallen off the screen in a way. His pieces were performed nationally and internationally, even leading to the culmination of his career in many ways with “Frederick Douglass”. But he’s fallen out of sight in a way. So one of the things we seek to do is to redress that wrong and bring composers who are important American composers into the light. So they’re part of the discussion. I always say: it’s hard to know where you’re going unless you know where you’ve recently been. And I think in the opera world, we often don’t look at our recent past and the contributions of composers like Ulysses Kay.

Rath: On a technical level, how difficult is it to, in a way, revive an opera? Pulling the materials together, making sure that you’re getting things right? How old was that?

Rose: Well, it depends on the opera. Some of them are easier than others. Some of them have been quite detective work, and I sometimes feel like the Indiana Jones of opera conductors. But in this case, the materials to do it were available. But for example, the players and the singers, and I are not used to working from manuscript scores. So I’m working from Kay’s manuscript in his hand, and the parts and the performing materials are all in a time just before, really, music was regularly typeset for dissemination. So that’s a challenge, and there’s no reference point for us. We can’t go to a recording or go to another performance on video. This is really kind of almost like doing a premiere, but at least some of the kinks have been worked out for us. So, I love second performances because somebody else has to always work out the problems. What we’ll hope to do is present this concert on [July] 20th and make the recording, and bring Ulysses Kay’s opera back to life.