Encore: Let's Get Naked

About The Episode

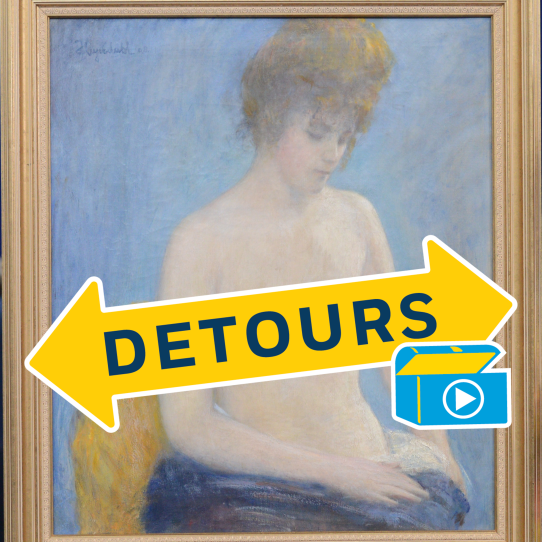

In 2014 a gorgeous painting was brought to GBH’s Antiques Roadshow in Bismarck, ND. The appraisal was selected by producers but ultimately cut from the episode before it aired. What made this piece of art so controversial? The late 1800s oil featured a nude woman. Join host Adam Monahan as he uncovers the tricky question of which parts of the body can be shown on broadcast TV and how issues of culture, politics, religion, viewer complaints and FCC regulations all play a role. But does this painting get a second chance on the airwaves?

Adam Monahan So the subject that I'm going to surprise you with... because I like doing these surprises.

Marsha Bemko Another surprise, Adam? I don't know if my heart could take all these surprises.

Adam I'm talking with my boss, Marsha Bemko. This one I was actually nervous about talking to about because at first I thought it was like, we've done a lot of our mistakes. This is not a mistake.

Marsha Okay.

Adam This is one that tells the inner workings of us as a show and us as a country. And what I want to talk to her about is an appraisal we filmed, but chose not to broadcast. As far as I know, Marsha made the call to cut it. I'm going to now share screen. There she is. Okay. This is the appraisal I am speaking to.

Marsha Oh, I know why I cut it. Well, what I'm looking at, everybody, is a gorgeous painting of a woman, but here's the thing I'm going to go ahead and say it, she's naked.

Adam Nudity. It's in every art museum. It's on social media, to a certain extent. It's even in PG 13 movies. But when you're making a primetime show for public television, which parts of the human body you do and do not show can be a tricky question. It's a question that involves culture, politics, religion, viewer complaints, FCC regulation, and in this episode we're getting into all of it.

Marsha I can't wait to hear what you find out.

Adam That makes two of us.

Marsha It's not a road. I thought I'd go down, Adam, but boy oh boy, I haven't seen that beautiful painting in a long time. So I got to thank you for that too.

Adam Plus we'll get the full story of that painting and how it finally got a second chance on the airwaves.

Adam I'm Adam Monahan, a producer of GBH's Antiques Roadshow, and this is Detours. Today let's get naked. I want to begin by covering some art history basics with the help of Allison Smith.

Allison I'm chief curator at the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Adam Well, thank you for joining us. To start, can you give us some big picture context? Why are European painters and sculptors so into naked bodies? Where does this artistic tradition come from? How did it start?

Allison Smith Well, the nude is a tradition which goes back to the ancient Greeks and to Greek sculpture. And the idea is that the nude body is something divine and beautiful and it can be used to personify abstract truth or allegorical virtues.

Adam So where does the shame and outrage over nudity start? Like at least in the Western world, was there always a sense that the body is something that should be covered in private or-

Allison This really relates to, I suppose, the establishment of Christianity, and the reaction against paganism and the idea of heathen idols and the idea that you should be still focusing on something beyond the body. So it's the idea that the body was to do with shame, Adam and Eve and the garden of Eden and the downfall of mankind, and to do with sex and sexuality. And I think it can slip from being the nude, the nude being something transcendent, into the naked. When you get into the idea of nakedness, that's when sexuality, immorality comes into play.

Adam So in European art, going back hundreds of years, you basically have this tension between two opposing traditions. The nude body as this classical ideal versus the naked body as something sinful and immoral. And as we get into the 1800s and 1900s, the issue only gets more heated, partly because more and more people are actually able to see fine art thanks to public art museums, affordable prints and later photographs.

Allison And so the question was who was going to pick them up, who was going to receive them and how they would engage with those images. So then you get the question about how art can potentially border on indecency or pornography. So context is key when we're talking about the nude.

Adam That will be true of our own nude painting as well. But before we get to that, I wanted a more visual sense of this distinction between nude and naked. So I visited one of these so-called art museums I've heard about where the common folk like me can come have our minds corrupted.

Claire Whitner [inaudible] [crosstalk] place to start would be.

Adam Oh, here's a good place to start.

Claire Yeah. Yeah, the old masters are a good place to start thinking about the nude and its place in the Western... [Inaudible].

Adam Claire Whitner is a curator of European art at the Worcester Art Museum, and she gave me a tour of some of their nude highlights, which includes a five foot tall painting of the Roman goddess Venus.

Claire And Venus is this goddess of love and she's associated with fertility.

Adam In the painting, Venus sits on a pile of silk cloth, gazing playfully down at her plump toddler son Cupid, also naked, who has colorful little wings sprouting out of his back.

Claire And she embodies a lot of the ideals of what beauty is at this moment, and we see sort of the light hair, the high forehead, the light skin. I mean, we can see her exposed breast, but you cannot really see her genitalia. There's just a suggestion of that with her crossed legs.

Adam The whole painting has kind of a soft glow to it as if it's not of this world at all.

Claire And her body is sort of hairless. This does not look like a naked body, that this is an idealized form.

Adam This Venus painting is from the mid 1500s, so right in the middle of the Renaissance, and it's very typical for this period. Most of the Renaissance nudes, we looked at show scenes from mythology, history or the Bible, not portraits of actual living people.

Claire We're not just looking at pictures of people without clothing on.

Adam But Claire had another painting in mind that offers a very different vision of the naked body, so we continued our tour.

Claire [crosstalk] ... keep moving through the Dutch generally and we ... [inaudible] everybody's got their clothes on.

Adam This painting she wants to show me is from 1901 by a German artist named Paula Modersohn Becker.

Claire What I think in is so shocking about it is first of all, it's a nude painted by a woman, and everything we've seen thus far are works by men. And it depicts three naked boys.

Adam But these boys are not idealized like the little Cupid in the Venus portrait.

Claire What we see here are the young boys that are playing in the canals in Worpswede, and you can see how disfigured their bodies are, that this is not a wealthy part of Germany at the time. You see distended stomachs, which potentially indicates starvation among that population. In fact, their disfigurement is almost emphasized in her work.

Adam This painting of the three boys is an extreme example of just how unidealized the naked body can be, but it's certainly not unique. In the mid to late 1800s you had French artists like Edward Manet, painting nude portraits of regular people, not mythical heroes and goddesses. Manet's subjects did conform with the ideals of beauty and specifically female beauty, but their bodies were painted with sharp lines, clear light, and in natural poses. This was a real departure from Renaissance paintings like the Venus I saw where the nude bodies seemed to almost float on the canvas. In the work of Manet or Modersohn Becker, the nude bodies feel present and real.

Claire The 19th century really starts playing with that sort of thin line between nude and naked, and naked seems to be signaled by very specific people so that this is a specific person, and this is not the apotheosis of sort of the human form.

Adam The painting that came on our show dates from this same time period, the turn of the 20th century. It is also by a European artist who also chose to paint a very natural, realistic image of a human body and it sparked a debate within our team about what kind of nude, or perhaps naked images, are appropriate for our show. So let's turn to the appraisal itself. This was in 2014 at our event in Bismark, North Dakota.

Deborah Spanierman So ... [00:09:15], what can you tell me about the painting that you brought here today?

Guest: Well, it belonged to my mother who got it from her sister and we don't know where her sister got it.

Adam The painting is by a Norwegian artist from the late 1800s named Hans Heyerdahl.

Deborah He was born in 1857 and he died in 1913.

Adam According to our appraiser, Deborah Spanierman, Heyerdahl spent time studying in Paris and was greatly inspired by what the impressionists were doing in France at the time, the way they used small brush strokes and depicted everyday scenes. He even won an award for his work at the Paris World's Fair.

Deborah So he had a pretty good reputation when he was painting during his lifetime.

Adam When I showed an image of the Heyerdahl painting to Allison Smith from the National Portrait Gallery in London, she told me it's relatively unprovocative for its time, partly because of the woman's downward gaze.

Allison She's modest. More controversial artists at time would be like Corbe or Manet who painted nudes which engaged directly with the spectator.

Adam Meaning that the subject in the painting looks straight out, seeming to make eye contact with the viewer.

Allison And when a woman looked directly at the viewer, that was controversial, it's like an invitation to sex or some sexual encounter, whereas this, the Heyerdahl nude, is looking demurely away.

Adam That said, the woman in the painting is very clearly a regular person. Her hair is worn up in a contemporary fashion for her time, and there is nothing else in the image to provide any kind of narrative or setting. She's painted against a pale blue background, sitting on a chair with a yellow cloth draped over the back. There's no baby Cupid, nothing to indicate it's a Bible scene or a mythical interpretation. It is what Claire Whitner at the Worcester Art Museum called a decontextualized nude. It's just a painting of a person with no clothes on.

Deborah [crosstalk] ... modern expressionist style. And I really loved this painting when I first saw it because of the palette and the beautiful way that he treated the figure of this beautiful girl.

Adam Our senior producer, Sam Farrell liked the painting too. He made the call to tape the appraisal and the whole thing went off without a hitch.

Deborah So I can tell you that in the auction market, another painting very similar to this sold in Sweden in 2010 for almost $62,000.

Adam Oh, and it's worth real money too.

Deborah Oh. So based on that, I would suggest an insurance figure of about $75,000.

Guest Oh my goodness.

Deborah Are you surprised?

Guest Yes. It's hanging in my dining room.

Deborah It might be time to have it insured.

Guest Yes.

Deborah Should we get you a chair?

Adam Gets me every time.

Marsha And when I got home and I was watching that footage, I said, "Who picked this?"

Adam Again, my boss Marsha.

Marsha And I knew without asking that it was Sam Farrell, so I'm going to throw him right under the bus and I'm like, "Sam, what are you thinking?" Because just for everyone to know, Sam is our senior producer. One of his responsibilities is to make sure we follow the rules. So the irony of it, because he loved the painting and he couldn't resist picking it, but I did give him a little spanking for it. I did say no more of that.

Sam Farrell Yeah. I do remember Marsha came to me and said, "Who picked the painting with the boobies?"

Adam Here's Sam to defend himself.

Sam I agree that if one is exhibiting nudity for the sake of titillation, that would be without taste, but this was a carefully considered painting by a very accomplished artist and is a beautiful work of art.

Adam Do you think, looking at this painting that the people who are making the Roadshow for the BBC or in Sweden would have any problems with this painting?

Sam No. I think the European or the larger European sensibilities are much more free and they are quite happy to include images of nude female and male forms in the art that they consider mainstream.

Adam I decided to do a very limited test of that hypothesis using my in-laws. My wife is from Sweden. We go there every year or so, and it's been real cultural learning experience for me to figure out things like when you do and don't wear a towel in the sauna. In any case, I showed my in-laws a picture of the painting and just asked if they saw any potential issues with putting it on TV.

Adam's in-law I don't know. No. I don't see what-

Adam Okay. So hand it off.

Adam We pass it around in the whole room, but they were stumped.

Adam's in-law No. There's nothing that sticks out here. I don't know what this yellow thing in the background is though, but no, it's not controversial to me at all. No.

Adam And eventually I just had to give some help. So the answer is you can see that woman's boobs.

Adam's in-law In a painting.

Adam They found the answer extremely amusing.

Adam's in-law Oh, is that controversial in the US?

Adam Yes. I'm afraid it is.

Adam's in-law No.

Adam After the break, I talk with a communication scholar about nudity and American television. Plus, my colleague Sam gets to have the last laugh.

Adam I studied TV production in college, which means I learned the very basics about the big scary FCC or Federal Communications Commission. I know roughly what you can and can't do on TV, but I don't know why and since when and exactly how those lines are drawn. For that, I'm going back to school with Dr. Kyla Garrett Wagner, who also just happens to teach at my Alma mater. Now, Dr. Wagner, can we just briefly discuss how brilliant people come out of Syracuse University every year and are you one of them?

Kyla Garrett Wagner Well, I had the great privilege of getting to teach at Syracuse University, which really, I mean, that's just the highest honor is not only did we get to produce them, but I get to be part of producing those outstanding people. But I do have to toss in a quick hurrah to my undergrad, the Boilermakers of Purdue University, and my master's in PhD at UNC Chapel Hill. So go Tar Heels.

Adam Okay, wonderful. Let's not talk about them. They're not as great.

Kyla Oh no.

Adam But the reason I'm contacting you is I'm a TV producer and I'm trying to understand why we can and can't show certain parts of the human body on TV, and I'm hoping you can help me make sense of it.

Kyla So my background actually is in sexual and reproductive health. My research as a master's student and a bit into my doctorate work was all about actually the access to emergency contraception, also known as the morning after pill. And so what brought me to understanding the legal side, the free speech and free expression side, is because the work I was trying to do as a sexual health educator and researcher was being hindered by regulations that say, well, we don't protect this type of expression. And so that is what led me to this rabbit hole of research and a true passion for understanding the chaos that is sexual expression law.

Adam Wow. You are the perfect person for me to talk to then. For this conversation, I'm specifically interested in nudity. Like, can you give a basic history of nudity on television? When does it first become an issue even, and how have the rules changed over time?

Kyla Well, this will be a short conversation because there's no history of nudity on television.

Adam Should be clear here that for this conversation, when we talk about television, we're specifically referring to broadcast television. What you can pick up with a simple antenna. We're not talking about Netflix, HBO, or other special order channels, which obviously play by their own rules.

Kyla And it's interesting because nudity, whether it's been in a sexual context or the sake of art, expression or dance, it's been around for millennia. We can date way back to the Greeks and the Romans and their very explicit, very expressive sexual art.

Adam But this kind of expression has a very different history in the US.

Kyla We have a historic practice dating all the way to the country's founding that says, well, sexual content just doesn't get the same level of protection as other types of speech, say political expression or even commercial speech.

Adam The control of sexual expression in American media goes way back before television and even radio. In the 1870s, Congress passed what was known as the Comstock Act, which made it illegal to distribute printed material that was "obscene, lewd or lascivious." The law was named for Anthony Comstock, who has been called America's first professional sensor. Comstock himself was eventually appointed a special agent of the US Postal Service, and he used this job to confiscate packages containing nude photographs, and even arrest doctors who mailed their patients information about how to prevent pregnancy. But even that didn't go far enough for some states. By the end of the 1800s and into the 1900s, many states adopted their own Comstock laws as they were called to further limit various forms of sexual expression.

Kyla And so as more media came onto our history, for example, the development of television and then people being able to gather around to watch the evening news or wonderful mainstream television like I Love Lucy, there was a real push to keep that content clean. The irony though, is as time has gone on and more types of media have developed, the rules around indecency seem to be thrown out except for in broadcast media still today. Broadcast media is still really the only form of media held to this high standard of prohibiting nudity because it is indecent.

Adam It's strange that broadcast television is what is singled out here. It's like, no, it's indecent for that, but at your museums, it's seemingly not a problem.

Kyla I'm really glad you bring the example of attending a museum and why it seems to be okay that we can come in contact with not just nude artwork, but even explicit artwork. The trick is you chose to go to the museum.

Adam That idea of choice was at the center of a famous case from the 1970s, FCC versus Pacifica.

Kyla Which if you're unfamiliar with it, it's the case in which the FCC fined a local news station in New York because they aired George Carlin's seven dirty words and they aired it in the middle of the day.

Adam This bit by George Carlin is specifically about the arbitrary nature of obscenity in, this case for language.

George Carlin What are these words that I'm talking about? They're just words that we've decided, sort of decided not to use all the time. That's about the only thing you can really say about them for sure.

Adam So he comes up with a list of all these words you can't say, which for this PG-13 podcast and any cautious broadcaster sounds, something like this.

George And all I could think of was ... [inaudible].

Kyla And the FCC received a complaint, actually only one complaint, but is from a father driving his son around and that broadcast was aired and the little boy heard it. And the father was very upset that his child, his innocent child, had been exposed to such indecent content. And so the ruling from that is what set this idea that we will treat broadcast differently than pretty much all our types of media and other types of spaces. Broadcast, even still today, is media that the audience cannot control.

Adam So just like Allison Smith said about nude art in the 1800s, context is key. It's not so much about what is being shown. It's about where and how an image is shown and who it is shown to.

Kyla And we have asked the Supreme Court multiple times since that major decision in the 1970s to address this issue and time and time again, the Supreme Court don't really want to answer that question.

Adam So the Pacifica ruling, which limits free speech just for broadcast media, still stands today.

Kyla But I can point to, in addition to an opinion from Ruth Bader Ginsburg in the case FCC versus Fox Television in 2012, where she said herself, the rules and regulations as set forth by the FCC versus Pacifica in the 1970s, don't really apply in 2021 because there's now so much more content. People are so much more engaged and I get to pick what I get to watch. If I don't like it, I'll change the channel. And so your question brings up this point that I would argue in my professional opinion is the laws are out of date and they don't reflect not only what public opinion and public acceptance of sexual expression and sexual content and nude content would say today, but it seems inconsistent that we're pretty much singling out broadcast media and inherently treating it differently just because it's, I guess, an old school media.

Adam How does the FCC draw the line today? Like what counts as indecent material?

Kyla I'm glad you asked because that also speaks to some of the chaos. I actually have pulled up for today's conversation, the policy, or at least the definitions from the FCC and its definition of indecency and profanity and obscenity. And what I'll focus on is indecent content, because to be clear, at least with the information that's published today, the FCC doesn't say it will punish you for nude content, but the definition for indecent content does say, "Portrays sexual or excretory organs or activities in a way that is patently offensive, but does not meet the three prong test for obscenity." So to be clear, obscene content is always illegal, but the definition put forth by the FCC in terms of indecent content is it has to be sexual or anatomically involving the human body, but in a patently offensive way, and that's a pretty broad term when we definitely debated. And I'm not really sure, nudity alone really stands for being indecent, yet that is what the practice is today.

Adam And it is definitely the practice on GBH's Antiques Roadshow. No one at the FCC told us we couldn't air the Heyerdahl painting. We made that choice ourselves because anytime we do feature something even remotely potentially indecent, we flag the episode so that stations can choose whether or not to broadcast it. Many of them simply won't air any of our flagged episodes, probably because they are worried about complaints from viewers, like that guy who wrote in about the George Carlin skit. So in our case, however inoffensive the painting may be, it's easier to just play it safe.

Kyla The truth is the FCC has really waned in its enforcements of indecent content. The last real major case was in 2015, and that's because a local news station accidentally showed an image of a female adult entertainer, and in the screenshot there was a very obvious depiction of the male genitalia and actions being taken upon the male genitalia in that image. So that actually got the news station a total of $325,000 in FCC fines, but that's really the only case I can point to.

Adam That makes perfect sense. People might lodge complaints, but the FCC would never go after PBS for showing an image like our painting.

Kyla My professional argument would be exactly that. We've seen some racier things come up in public broadcast in the last handful of years. PBS has aired a series of informational sessions and broadcasts about sexual health, reproduction. So just the mere discussion of sex or nudity is not grounds enough. And another good example of the FCC getting complaints, but doing nothing with it would be the Super Bowl halftime show.

Adam This was the 2020 halftime show featuring Jennifer Lopez and Shakira.

Kyla And the FCC got something close to 1500 complaints from family members upset about the pole dancing and gyrating that was taking place during the show, which was publicly broadcast during the hours in which children would be in the audience. But the FCC didn't file any complaints because there was no violation of at least the FCC's policies. But this still doesn't mean people don't have the ability to air or their grievances, and that's something that broadcasters like PBS are paying attention to because they don't want to turn away their fan base.

Adam Yeah. So can you just weigh in? You've seen the painting. Can I get your opinion on whether it's broadcast worthy?

Kyla My first impressions of the art is that not only is it protection worthy, but it actually speaks to a growing issue that's getting attention in first amendment law, which is essentially what looks like sexual discrimination in which the reason this painting is problematic is because it shows the female breasts. But if it was a gentleman shirtless, we wouldn't have any issues with it. And it actually makes me think of a campaign going on that's probably been in existence for about 10 years now is the Free the Nipple campaign because that's really what's most problematic here is just that you have a bare woman's chest and in a very body positive light, by the way, that seems very realistic of what women can look like. So what's the harm of having an honest depiction of the female body? In fact, that speaks to the great social movements going on in the United States right now and all over the world.

Adam Eventually the Heyerdahl painting did get a second look, but only because we were desperate. After that show from North Dakota aired, we learned that one of the other objects we appraised, a George Washington letter was a forgery. We did get a couple of viewer emails about that one. So when it came time to rebroadcast the episode, we yanked the letter and replaced it with the painting. In a pinch, with a gap to fill, Marsha gave the okay.

Adam So it eventually did make it to TV. Do you have any satisfaction in that?

Sam You know, I pick a lot of things and a lot of things make it and a lot of things don't.

Adam Again, my colleague Sam here to gloat.

Sam I felt I was right at the time, so maybe I'm still right.

Adam Oh, and that is what I want to tell you. I asked Joe who takes the viewer email. We have received zero emails about this since it did air.

Sam That could be because the people who don't like this sort of thing prevented it from being broadcast in the sort of places where people would object. But it also could be, as I suspect, that it's a beautiful piece of art and nobody was offended.

Adam That gives me some hope that maybe American television viewers are a little more open to nudity than we give them credit for. Perhaps it's time to go back through our archives, dig out all the old appraisals of nude artworks and let them finally see the light of day.

Marsha I think all of your listeners need to tell us whether or not they want a special everything's naked. So, I mean, it would just be a whole show of stuff that you've never seen before and everything's naked. We're here to make that special for you.

Adam And if you'd like to see that special, please let us know. Personally, I think it's about time.

Adam This is the last episode of the season, but if you scroll back in the feed, we've got two years worth of stories in there about everything from stolen lamps and looted artwork to Mayan artifacts and Rolex watches. Check it out. Detours is a production of GBH in Boston and PRX. This episode was written and produced by Ian Coss. Our assistant producer is Isabel Hibbard and our editor is Galen Bebe. Jocelyn Gonzalez is the director of PRX productions. Devon Maverick Robbins is the managing producer of podcasts for GBH, and Marsha Bemko is the executive producer of Detours. I'm your host and co-executive producer, Adam Monahan. Our theme music is Once in a Century Storm by Will Dailey from the album National Throat. Thank you all for listening. Have a good one.