It Was Just Too Exciting

About The Episode

Edward Field grew up feeling out of place in Long Island, New York, a gay, Jewish “interloper.” When he joined the Army Air Corps in 1942, he felt he’d “escaped from a world I didn’t like to one I did.” Field became a navigator and flew twenty-seven missions over Germany. One mission ended in a crash landing in the North Sea and an astonishing act of altruism.

For more powerful memories from veterans, visit the PBS series, American Veteran, where you can also watch the television series and digital short films.

Learn more about American Experience

Follow the show on Instagram, X, Facebook, Threads

FIELD: The thing about combat is that the natural fear you would feel, turns to excitement, and you get hooked on that excitement. I volunteered for missions because I couldn't stop. It was just too exciting.

Producer: You never found anything to match that before?

FIELD: Uh, well, sex.

KLAY: From Insignia Films and PRX for GBH, this is American Veteran: Unforgettable Stories. I’m Phil Klay.

I’m a veteran myself, I served in Iraq with the Marines from 2007-2008 and now I write books about war.

In each episode of this podcast, we’ll hear one American vet tell us: Who they were before they joined, what they did in the service, and who they became afterwards. These are their stories.

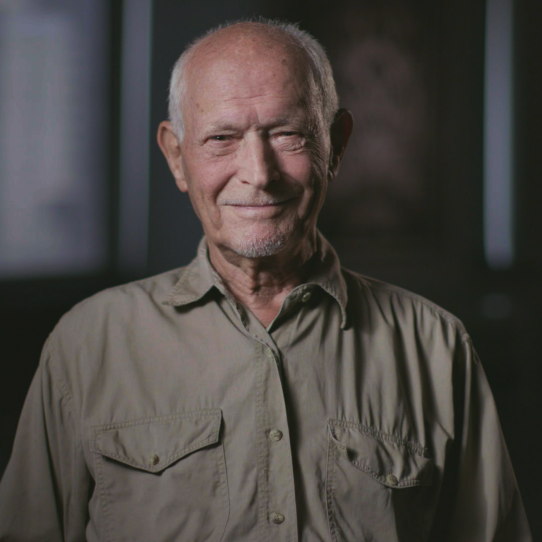

KLAY: Edward Field was interviewed in a TV studio in New York for the American Veteran documentary series.

FIELD: Well, I’m not so mobile as I look because I can’t really walk more than a few blocks without resting.

KLAY: Edward Field was born in 1924, which makes him 97 years old when this podcast was recorded. He may not be able to walk far, but his mind is sharp. This may have something to do with the central preoccupation of his life...

FIELD: Really, I think of myself as a poet, not as a veteran (laughs), though, of course I am a veteran, but the thing about poetry, everything you experience is material.

Poem:

It was over Target Berlin that flak shot up our plane

Just as we were dumping bombs on the already smoking city. [fade under]

FIELD: So everything I’ve been through has been material for my poetry career. I’m just- I’m very happy about everything that’s happened.

KLAY: How many of us are able to say that? That we’re very happy about everything that’s happened? But it’s especially extraordinary for Edward Field to say, because not everything in Field’s life was happy. We can start with when he grew up…

FIELD: America before the war, was very racist. And the world, it was very hostile to Jews. They just didn't want us.

KLAY: Then there’s where he grew up… a small town on Long Island

FIELD: We lived in a town that did not welcome immigrants. My parents were immigrants from Eastern Europe, and even though they lived here since childhood...they grew up on the Lower East Side, they wanted to live in the real America, and they wanted us to grow up in the real America, but the real America did not want us.

FIELD: I was a dark little kid with curly hair, and looking at pictures of myself now, I see I was very good looking, yet everybody made me feel like I was some dark Semitic interloper, and I got beaten up every day going to and from school. I really don’t understand how my parents accepted that, but it wasn’t a good place to grow up.

FIELD: It was a great relief to get out. Of course, New York City was not far off. Only 20 miles. So that was always a great escape.

KLAY: Edward was 17 when the U.S. entered the Second World War. He was taking classes at New York University…

FIELD: And I’d been enrolled in the School of Commerce, which I was very unhappy about, I never was academic, and I just had to get out of there, so I enlisted, and I escaped from a world I didn’t like to one I did…

FIELD: The military was cosmopolitan (laughs).

KLAY: The word “cosmopolitan” might not call to mind a bunch of sweaty recruits doing pushups while a drill instructor yells at them, but honestly, there’s nothing like common hardship to bind people together from radically different backgrounds.

Before the draft board called him up, Edward enlisted in the Army Air Corps, the predecessor of the United States Air Force.

When I was in the Marines, we used to complain that the Air Force got swanky facilities while we lived in dirt. And Edward’s training experience fit the stereotype.

FIELD: My basic training was kind of luxury. It was in Miami Beach. We lived in the hotels, the tourist hotels. My hotel was The Caribbean. It was very comfortable, though they moved out the beds and the carpeting, and put in bunk beds, but it was still fine, and we paraded on the golf course. Learned to shoot and all those things were really quite nice.

KLAY: After roughing it through boot camp, Edward was ordered to go to clerk typist school. The military was, among other things, a vast and growing bureaucracy. Everything was recorded on paper, from personnel files to budgets to battlefield orders, and it all had to be meticulously typed out and carefully filed. Clerk school was all the way out in Colorado…

FIELD: And we were getting on the train, and a Red Cross lady was handing out a little care package to everybody, and my care package had, of course, toothpaste, and toothbrush, and comb, a...stuff like that, and a paperback book, and my book turned out to be an anthology of poetry edited by Louis Untermeyer. And I read it the whole way across the country, all three days, and when I got off the train, I knew what I was going to be. I was going to be a poet.

FIELD: That actually was one of the key moments of my life that the Army gave me.

KLAY: Edward didn’t mean that he was going to be a war writer, like Wilfred Owen or, later, Tim O’Brian. It wasn’t exposure to death and violence that made him want to write poetry, but exposure to the broader world.

In the military, for the first time in his life, Edward found community with fellow Americans…

FIELD: The guys liked me. I was really amazed to be liked for the first time and accepted. So it was really wonderful.

KLAY: Being Jewish wasn’t a problem, and, believe it or not, neither was being gay....

FIELD: it was just not something you talked about. You didn't need to be identified. I had boyfriends in the Army. I can’t understand how, but it was perfectly open.

KLAY: This is a head scratcher. Openly gay in the Army Air Corps? In 1942? No way, right? Here’s how Edward explains it. After training in Colorado, he was stationed in Tinker Field, Oklahoma, now known as Tinker Air Force Base. In the barracks was a master sergeant with a big job flying around with generals in the Army’s legal department…

FIELD: Brilliant guy, and we got together, and he moved me into his room because he was allowed a private room in the barracks. It wasn’t considered odd. Now I would think how obvious it was, and yet nobody said anything, except in the office I worked in, there were civilian workers, women. Women noticed I was wearing his school ring.

FIELD: I did finally get fed up with him and I wanted to get away, but I couldn't just move back into the barracks from this room. So across my desk came a notice that the Air Corps needed aviation cadets desperately because of the planes being shot down over Europe. I immediately applied, and was accepted, which meant I was sent to San Antonio for testing to see where my talents were and to qualify, I had to be 128 pounds. I had never been over 122 pounds in my life. So I just ate bananas, and milkshakes, and malts, and I stuffed myself, and I still didn't make the weight, but the sergeant in charge was also very fatherly. I was a little kid, really. And he said, that’s okay. We’ll- we’ll pass you. And because I had high math scores, I was made a navigator.

KLAY: If you’re trying to get some distance between you and an ex-boyfriend, volunteering to go into aerial combat during World War II is a fairly unique solution.

Edward did a year of training. All in all, he liked being an airman. He says it felt glamorous. And it provided the stability he felt he needed.

FIELD: I liked the military life very much. It suited me. They took care of me. I’ve always found it a problem in life how to support myself, how to look after myself. I never even knew how to find an apartment. So, in the Army, I was really taken care of. They fed you. They gave you money for doing (laughs) ery little. I didn’t like a desk job, so I was very happy to go into something more active, but the regular military routine was very congenial to me.

KLAY: But of course, there was a war going on, and thousands of American airmen were getting killed. Replacements were desperately needed. In late 1944 Edward was sent to the European theater. The Normandy invasion had taken place earlier in the year, and the Allies were rapidly advancing in western Europe, on the ground and in the air.

Archival audio: “France is freed as the full fury of America’s mighty war effort is unleashed.”

KLAY: Edward was the navigator on a B-17, a heavy bomber with four engines known as the Flying Fortress.

Archival audio: “Eighth and ninth Air Force pilots hit where it hurts.”

KLAY: Hundreds of these planes would take off together on bombing runs from England to Germany, and not all would return. Over the course of the war, the United States lost over a fourth of the planes it put into the sky. That meant any bombing run could easily be a crew’s last.

FIELD: Flying over the target, you went through literally a field of bursting shells with flak flying all over the place. The plane bumped through the flak because the exploding shells under you, and coming through the thin walls of the plane, sharp shards of steel rattling around in the cabin, and on my first mission, the bombardier in the nose of the plane, he was a married man with children, and was trembling, and he asked me to come and hold his shoulder while we went into combat.

FIELD: He was terrified, and they grounded him.

Producer: But that’s not how you felt.

FIELD: No. (Laughs) It was the most exciting thing in the world to go over the target.

FIELD: And so when we were flying over the target, I was supposed to be writing in my log what I saw and what time, and of course, my hand was shaking (laughs), and so that was fear, but it was also excitement, and I always had to show my log to the intelligence officer when we came back and my handwriting was shaking, like my hand shakes now as an old man.

KLAY: Edward said his worst mission was his third.

FIELD: We had been on a flight to Berlin and got shot up very badly, and then we limped back with two engines, and then the gas was streaming out of the tanks and the wings. The tanks were in the wings, and the flak had just peppered the tanks with holes. So we were losing gas. The engines were damaged from the flak, and we got over the Dutch coast, and then gas really ran out, and we had to get low over the water, and we ditched the plane.

[MIDROLL]

FIELD: When you hit that water, even slow as we were going, it’s just like hitting a brick wall, and you pass out. You...you pass out and then come back again, and the water’s rushing in, so you’ve got to get busy and get out, but everybody climbed out of a hatch on the top of the plane. There was supposed to be two rubber rafts that popped out of the side of the plane but only one of them inflated, and though the other one was really only half inflated. And I got out last with the radio operator, and when we got out, the crew had all gotten into the good raft and floated off, and we were standing on the wing (laughs), and had to swim for the rafts.

FIELD: Of course, one raft was barely inflated, and the pilot was lying in it, with water washing over him. There were mountainous waves. It was February. The water was ice water. I swam for the crowded raft with the crew in it, and when I got there, I just had to hang on the side. There was no room for me. We had a ditching manual that said you could live 25 minutes in the water. I said to the guys, come on, move over. Make--squeeze together, but they were afraid that the raft would be overloaded, so they didn't, and I was hanging on. I was getting numb, I kept saying, come on, guys. Let me on, and a kid, a gunner, the ball turret gunner, a kid I hardly knew, he suddenly got up, and he took his clothes off and jumped in the water and gave me his seat. Of course I got in the raft.

FIELD: He did work to pull the two rafts together. Of course, we all had to help and paddle with our hands, and he got into the other raft which was full of water. It was hopeless.

FIELD: My life was saved, and he gave up his life.

Poem:

That boy who took my place in the water,

Who died instead of me,

I don’t remember his name even.

It was like those who survived the death camps

By letting others go into the ovens in their place.

It was him or me, and I made up my mind to live.

I’m a good swimmer,

But I didn’t swim off in that scary sea

Looking for the radio operator when he was washed away.

I suppose, then, once and for all,

I chose to live rather than be a hero, as I still do today,

Although at that time I believed in being heroic, in saving the world

Even if, when the opportunity came,

I instinctively chose survival.

FIELD: We were in the boat a couple of hours, and the planes were flying back overhead from the mission because a thousand planes went on that day, and they were all flying home, and we did send up rockets. We had flare rockets, and we were finally spotted by an English air-sea rescue boat. They picked us up, and of course, they took the two corpses up, too, the gunner and the pilot, and they took us to a rest home on the Irish Sea.

Tape: Mr. Speaker, I rise today to honor the life of Sergeant Jack Coleman Cook of Hot Springs, Arkansas, for his heroic actions in World War II. [fade under]

KLAY: As Edward said in his poem, he didn’t know the name of that ball turret gunner. But recently a researcher identified him. And in 2018, the congressman from his Arkansas district paid tribute to Sergeant Jack Cook on the floor of the House…

Tape: Sergeant Cook got into the water so the crew’s navigator could get out of the cold sea and take his spot in the raft. The sergeant then swam for forty-five minutes until they reached the second raft. Shortly afterward, Air-Sea rescue located the crew, but Sergeant Cook had little life left in him, and he passed away on the boat.

FIELD: We were the same age, really. I was an officer, but we were really no different, and he gave me my life, that boy.

KLAY: After a few weeks of R&R, Edward flew more missions. Twenty-four more, to be precise, for a total of twenty-seven. Now, a full tour of duty was considered twenty-five missions. After that, crews could return home. Provided they survived, of course. But Edward, despite all he’d been through, and despite the terrible dangers, kept volunteering.

KLAY: By 1945, that danger took on a new, and lightning fast form. The Germans didn’t have any more Messerschmidt fighter planes to send up against Allied Bombers. But alongside deadly anti-aircraft shells, there was a new weapon: The Germans had invented the jet engine…

FIELD: I think it was in March ’45, they sent up a squadron of jet fighters, and they tried to break up the formation by zooming between the planes ‘cause they were so fast, and that was my one chance of shooting my machine gun, which was in the side window of the nose of the plane, and so I left my desk, and I aimed it--I was a terrible shot, and I did shoot at the planes as they flew by. It’s hard to explain, but it was really all tremendously exciting. Of course, then I had to clean the goddamn guns when I got back.

KLAY: The excitement Edward felt in combat isn’t rare. As Churchill once said, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” If you talk about enjoying war, though, people tend to look at you strange, so a lot of vets stay stoically quiet. Edward is unusually candid about it.

He was also excited about another aspect of military life. The one hidden in plain sight….

FIELD: Gay life in the military was...was really quite extraordinary. I remember once I was on a courier run after the war, flying generals and high brass around, and we went to Paris. So I had a night in Paris, and I went to a nightclub on the Champs-Élysées called Le Boeuf sur le Toit and it was a totally gay club, filled with military from all over the world, every rank, and I had never dreamed there were places like this in the world. I also went to a gay club in London called The White Room where people said, oh, when you go back to New York, you must go to this bar or this restaurant, and then I discovered, coming home, that there’s a whole gay world that I didn't know about.

KLAY: Edward came back from the war understanding more about the world, and the possibilities for people like him, than he ever could have imagined and the war also changed American culture.

FIELD: After the war, one of the major differences was the abatement of anti-Semitism because of the camps, discovering the camps, and then the foundation of Israel. Jews became respectable. And so even though I had my personal psychological problems to get through, it was a much better world.

KLAY: Edward’s psychological problems weren’t simply about his war experience so much as about his identity… who he was going to be.

KLAY: He went back to college, dropped out again, then spent some time in Paris, to become a poet...

FIELD: As people did back then. But there was no way I could live as a poet. I had no academic credentials for teaching. I really couldn't do anything except type maybe, and I didn't want to be a typist. So I really was a wreck, and I even returned home to my family for a while, and I just didn't know how to live as an adult.

KLAY: This was especially difficult for him as a gay man. For psychiatrists at the time, homosexuality was seen as something to be cured.

FIELD: It was a period when you were supposed to go straight, and in fact, when I went to psychiatrists, they assumed my problem was that I was gay and that I should go- go straight. And in an era when homosexuals were being persecuted like communists, we were being fired right and left from jobs. It was a time when I fell for it, too, and so for a few years, I tried to go straight.

KLAY: At the time, even though he didn’t want to be a typist, that was how he earned money. And this turned out for the best...

FIELD: I was working at a typing pool on Madison Avenue, and the supervisor of the typing pool brought a young man over and sat him down at this typewriter next to me and said, oh, I think you’ll get along. And we talked the rest of the day. And that turned out to be my partner. We lived together 58 years (crying), and he just died (sighs), but it was something that was so marvelous…

KLAY: Edward has published many books of poetry over the years. He’s edited anthologies. He even won an Academy Award in 1965 for writing the narration to a documentary called To Be Alive.

He credits his military career, and his life-long relationship, for his good luck...

FIELD: It was after we got together that my first book was published, and then my poetry career was also launched. So I’ve really had an incredible life.

[CREDITS]

KLAY: American Veteran: Unforgettable Stories is a production of Insignia Films and PRX for GBH. The lead podcast producer is Curtis Fox, the composer and sound designer is Ian Coss, and the executive producers for Insignia Films are Amanda Pollak and Leah Williams. Stephen Ives did the interview with Edward Field. Thanks to Kathleen Horan and Matt Gotteseld for their research. For GBH, Devin Maverick Robins is managing producer, and Judith Vecchione and Elizabeth Deane are executive producers.

KLAY: Funding for American Veteran: Unforgettable Stories was provided by The Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Additional funding was provided by The Wexner Family Charitable Fund, Battelle Memorial Institute, JP Morgan Chase, and Analog Devices.

KLAY: For more powerful memories from veterans, visit PBS.org/American Veteran, where you can also watch the American Veteran television series and digital short films. You can also learn more by using #AmericanVeteranPBS.

I’m Phil Klay. Thanks for listening.

[GBH sting]

Note: Red text denotes Archival Transcription.