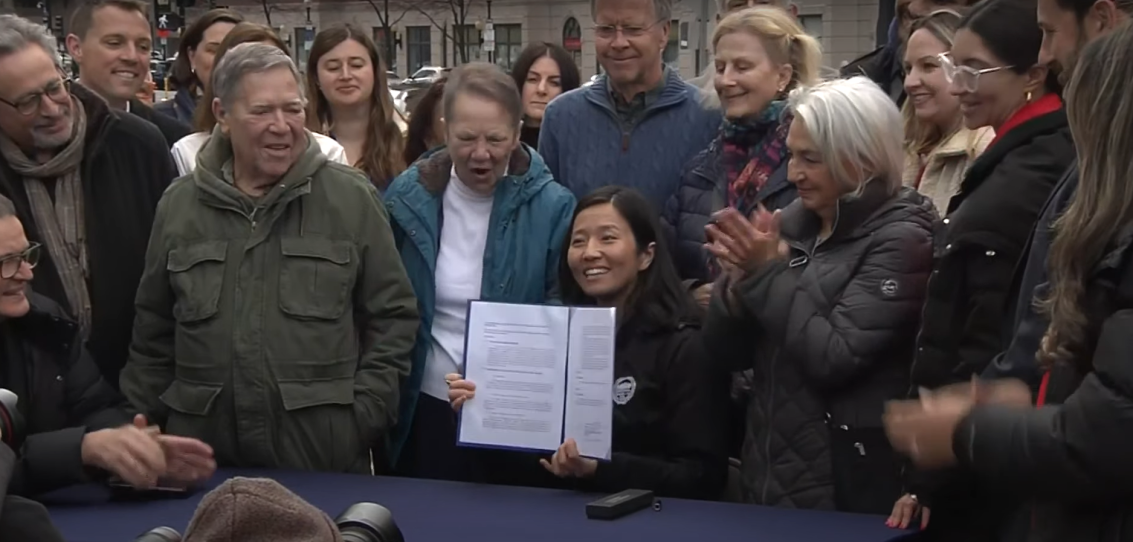

On the afternoon of Tuesday, April 2, 2024, Boston Mayor Michelle Wu signed an ordinance creating a new planning department in the city of Boston, a move she said will make planning and development in the city “more predictable, more transparent and more trustworthy.”

Here are five notable aspects of the change.

The mayor is delivering on a longtime policy goal.

In October 2019, a year before she announced her mayoral bid, then-City Councilor Wu released a hefty, detailed report arguing that the Boston Planning and Development Agency should be abolished. Wu said the BPDA — which controlled its own finances and operated with minimum oversight — was privileging development over the concrete needs of Boston residents, and in the process exacerbating problems like economic inequality rather than ameliorating them. Because of that, Wu said, the BPDA should be replaced with a new planning agency that reversed that causal relationship and was fully integrated into city government.

As mayor, Wu shifted her pitch to radically reforming the BPDA, in part because outright abolition proved technically challenging. (Among other things, it required sign-off from the state Legislature in certain key areas.) The new ordinance, which moves about 200 BPDA staff into a new city planning agency, doesn’t eliminate the BPDA outright, but it comes pretty close.

While a weakened BPDA abides, more change may be coming soon

In the wake of today’s move, the BPDA will effectively consist of two boards that represent its two constituent entities, the Boston Redevelopment Authority and the Economic Development and Industrial Corporation of Boston. Those boards are officially distinct, but they share members and effectively operate as one body.

Even without the 200-some staffers that used to support them, those same boards have certain legal functions they’ll continue to discharge, including approving or rejecting certain real-estate transactions. However, the Wu administration has filed a home-rule petition at the State House that would merge the two boards and also rescind the BPDA’s urban-renewal powers, which enabled the taking of so-called blighted land for controversial projects like the razing and redevelopment of the old West End. (Not coincidentally, that’s the neighborhood where Wu signed the ordinance Tuesday, after decrying the damage wrought by the old status quo.) That home-rule legislation is still pending.

The Boston City Council was split on the move

When the Boston City Council approved the new ordinance in a meeting last week, five of the 13 councilors didn’t offer their support. The council’s (relatively) conservative bloc — Ed Flynn, John FitzGerald and Erin Murphy — voted no, while progressives Tania Fernandes Anderson and Julia Mejia voted present. As Adam Gaffin of Universal Hub reported at the time, Flynn and Mejia argued that the proposed changes still needed more discussion, while FitzGerald, who used to work at the BPDA, contended that the agency had actually done its job pretty well.

Moving forward, it’s reasonable to think that the five councilors who didn’t back the change will be the five councilors most inclined to subject the brand-new planning department to critical scrutiny. That’s especially likely because many councilors who voted for the change were backed by Wu in the most recent city election cycle.

The new planning department could bring political challenges for the mayor

Wu is engaged in an ongoing effort to reform Boston’s notoriously byzantine zoning code — in part, by offering a standardized array of options that would-be developers can pursue in certain settings as a matter of course, without needing to get buy-in from neighbors who might not be inclined to give it. (Development in Boston is often contingent on a developer’s ability to get zoning variances, which seem to be required as a matter of course and give neighbors who raise objections extra power.)

The new, mayorally controlled planning department should give Wu’s push extra momentum. But that same momentum could end up eliciting pushback from residents who aren’t thrilled at ceding the de facto veto power they’ve enjoyed for decades. Keep an eye on that dynamic as the 2025 mayoral election looms.

The Wu administration is working to get buy-in from BPDA staffers

Given Wu’s longtime characterization of the BPDA as an entity whose priorities are fundamentally flawed, it wouldn’t be surprising if some BPDA staffers who’ll be transferred to the new planning department are taking a bit of umbrage at the shift. But Wu lavished praise on them Tuesday, touting “the great work happening by all our city teams up at the BPDA” and “the hard work and talent of so many staff members.”

James Arthur Jemison, who’ll lead the new department and has also been leading the BPDA itself, struck a similar note, vowing to “ensure a smooth transition for our staff, who…are the reason we’re able to take any of the steps we take, and able to continue the growth the city’s been experiencing.” If there’s ill will among some of the BPDA staffers who’ll be shifting their jobs to the new entity, tributes like these could help ease it.