It’s been a year since a financial crisis brought the nation’s largest private for-profit hospital system, Steward Healthcare, to an abrupt end.

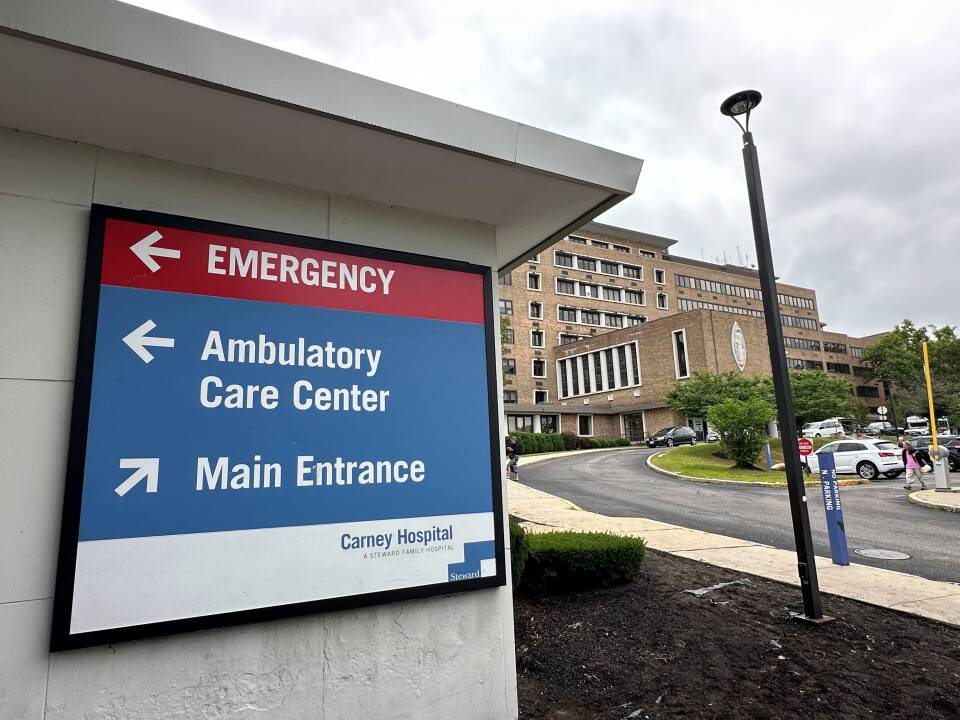

While the bankruptcy led to the sale of five Massachusetts hospitals, its lasting impact is most keenly felt in the communities around the two other Steward hospitals that closed at the end of last August: Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer and Carney Hospital in Dorchester.

Losing those hospitals and their more than 200 combined inpatient beds has increased demand on neighboring hospitals and community health centers — which were already dealing with capacity issues — and ambulances have been tied up driving patients long distances to receive emergency care, adding to longer response times. Meanwhile, efforts to restore medical services in those two communities remain ongoing.

“These hospitals are missed in the communities,” said Dr. Robbie Goldstein, the commissioner of the state’s Department of Public Health. “We knew that the emergency medical services system was under stress before the closure of the Steward hospitals. We certainly see it every single day post closure.”

Some other health care leaders argue the state should have been more actively involved in planning before the hospitals’ closures. Now, they say, the state could step in to limit the realized impacts and aid providers that are trying to fill the gaps in Ayer and Dorchester.

Here’s the impact on the ground, a year later.

Demand shifts to other hospitals and health centers

The loss of Nashoba Valley Medical Center left a health care vacuum in that part of the state.

A working group report showed the median EMS transport times in the region increased from 12 minutes prior to the hospital’s closure to 17 minutes afterward. The impact was particularly acute for patients who needed EMS transport from Ayer and Groton, where travel times spiked up to nearly a half hour — and those ambulances are unavailable to take subsequent calls until they complete the longer journeys.

After the closure, the majority of emergency patients in Ayer are being sent to UMass Memorial HealthAlliance-Clinton Hospital in Leominster, about 10 miles away. Most ambulances originating in Groton are sent to Emerson Hospital, about 18 miles away.

Justin Precourt, president of UMass Memorial Medical Center, said they saw the impact right away.

“It really created a void between Emerson Hospital to the east and HealthAlliance Leominster to the west. ... We saw really long trip times,” he said. “The impact on the EMS services in the cities and towns was really profound.”

Precourt said emergency room visits at HealthAlliance Leominster increased about 8.5% from prior years, and that boarding hours — the time patients spent in the ER waiting for beds — doubled in those first few months.

Demand is also shifting to other hospitals in Boston after the closure of Carney Hospital.

Bill Walczak, a former president of Carney Hospital who has also run a number of health care organizations, said Dorchester residents have few good options. Many don’t own cars, so getting to hospitals in other areas of the city is difficult. That has meant more patients going to busy hospitals or having to travel farther for care.

“Sometimes they get taken to Milton Hospital where they wait in long lines for being able to get care,” he said. “I suppose you could go to the Faulkner Hospital [in Jamaica Plain]. A lot of people go to downtown hospitals.”

Goldstein, who leads the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, said one of the “opportunities” that came from Carney’s closure was educating community members about other places they can receive care. Although he noted nearby community health centers have grown particularly busy.

“They have longer wait lists to get people in,” he said. “And we, the state, along with our partners across the region need to work together to address that capacity crunch that exists in the community health centers.”

The challenge of restoring health care services

A couple health care providers are stepping in to replace some of the services lost in Ayer, but there’s been little progress in Dorchester.

Following Carney’s closure, Dr. Bisola Ojikutu, Boston’s Commissioner of Public Health, co-chaired a “working group” to study the impact the loss of the hospital would have on the community and to make recommendations for addressing concerns. In April, the working group issued its report, including a recommendation that “local authority” should be used to ensure that health care services are included on the property.

Mayor Michelle Wu has said the property is zoned exclusively for a health care facility and that the city will block any attempt to develop it for other purposes. Yet, a year later, no plan appears to be in place to do that.

“The challenge is that we don’t own the land,” Ojikutu said. In the Steward bankruptcy proceedings, the property was transferred to a real estate company called Apollo.

“We are still discussing with the current owner of the site how things will move forward,” Ojikutu said. “I don’t think that there is an immediate plan for the city or the state to step in.”

A spokesperson for Apollo declined to comment for this story.

“We need the state to come in and come up with a plan ... We are allowing the marketplace to dictate how this stuff happens.”Bill Walczak, former president of Carney Hospital

The state helped coordinate the transfer of other Steward Hospitals to new ownership, including briefly taking ownership of St. Elizabeth’s Medical Center in Brighton during a transition period while Boston Medical Center bought the property. The difference with Carney, Goldstein said, is that there were no qualified bidders for the hospital. And no one has stepped up since.

“As of right now, the Department of Public Health has not heard from any hospital operator who is interested in operating the facility at Carney,” Goldstein said. “If that were to change, of course, we would have a conversation with that hospital operator and talk about what might be necessary to get a hospital up and running.”

Walczak, the former president of Carney Hospital, said state and city leaders failed to adequately plan for Carney’s closure. He said residents currently have unequal access to quality healthcare, and he’s urging the state “to take control of the property.”

“This is a failure of planning from the commonwealth of Massachusetts and the city of Boston,” he said. “We need the state to come in and come up with a plan that’s going to preserve services and make sense out of the system. And we don’t have that. We are allowing the marketplace to dictate how this stuff happens.”

Goldstein said the state isn’t in the business of running hospitals or emergency rooms.

“And so it is not appropriate for the state to step in and operate a facility on the Carney campus,” Goldstein said.

There’s been more movement toward replacing what was lost when Nashoba Valley Medical Center closed in Ayer.

UMass Memorial Medical Center announced a new “satellite” emergency facility in nearby Groton. Precourt said they plan to break ground in the fall, and expect to open the facility roughly a year later. The emergency center will include CT scanning machines and a helipad for emergency patients that need to be treated elsewhere.

“We anticipate that we’ll see anywhere between 15,000 and 20,000 visits annually,” Precourt said. “The community will now have access to a full service 24 hour a day, seven day a week emergency department.”

UMass Memorial has also added beds at its Leominster and Worcester facilities to help manage patient load.

Goldstein specifically highlighted services that were lost when Nashoba closed, including specialty doctors like pulmonologists and cardiologists. He said he’s hopeful they will be able to bring some of those services “back into the community.”

Precourt said UMass is not considering specialized services in the region at this time.

The Health Foundation of Central Massachusetts is also interested in offering more health care in the area, but it hasn’t decided yet what kinds of services it might provide. President and CEO Amie Shei said they’ve been working with local organizations and hope to sit down with state leaders to take the next steps.

Shei said the healthcare in the region has long been overlooked and underinvested in.

“We hope that the state will come to the table as an important partner and funder and support some much needed investments in this region,” Shei said.