Si desea leer este artículo en español visite El Planeta.

It was a gray April morning when 28-year-old Ely Rojas and his younger brothers were woken up by knocking on their front door. They didn’t know who was outside their Boston apartment, so they stayed quiet.

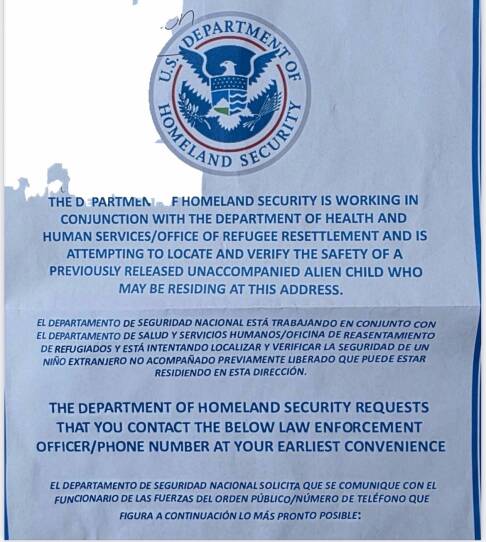

It turned out to be officials with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security conducting a “welfare check” on Ely’s teenage brothers, Juan and Jaime.

The boys, aged 13 and 15, came to the United States from El Salvador over a year ago, after their father abandoned them and their mother died of cancer. They entered the United States at the Mexican border with a group of fellow migrants. Initially held in federal custody, they were released to Ely, who’s now their legal guardian. GBH News is using pseudonyms for the three brothers, who say they fear deportation.

This type of unplanned visit from Homeland Security agents is a new development that’s left lawyers, advocates and guardians concerned.

Oversight of immigrant minors who were unaccompanied when they first entered the country has typically been handled by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, an agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, as outlined by the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000. Before that, custodianship had been under the now defunct U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, which had deportation power.

Legal advocates say they’re worried the Homeland Security visits signal a return to law enforcement agencies with deportation authority managing immigrant child welfare.

“It just inherently creates conflicts, and the tragic result can be the safety of the child,” said Wendy Young, president of the legal advocacy group Kids in Need of Defense. “Much of the activity that this administration is engaging in will drive children further underground and make them more vulnerable to child trafficking.”

The Department of Homeland Security argues the visits are meant to identify and stop trafficking, with a senior official claiming the Biden administration allowed unaccompanied children to be placed with sponsors who were “smugglers and sex traffickers.”

“DHS is leading efforts to conduct welfare checks on these children to ensure that they are safe and not being exploited,” the official said in a statement that claims the department has reunited 6,000 unaccompanied immigrant children with a “relative or safe guardian.”

Homeland Security officials didn’t respond to questions about whether those children were deported, and whether social workers from the Office of Refugee Resettlement were involved with the welfare checks. And the Office of Refugee Resettlement didn’t respond to requests for comment on whether the visits are part of a joint effort with Homeland Security.

For Ely Rojas and his brothers, the visit sparked anxiety and confusion.

An attorney for the family showed GBH News proof that prior to the check-in, they’d taken part in more than a dozen required calls with the Office of Refugee Resettlement. The calls help establish that immigrant children are enrolled in school, aware of upcoming court dates, and are generally safe. Despite that, Homeland Security agents showed up anyway.

“I was worried,” said Rojas, who went to the Boston Police Department with his concerns. “I asked if there was a problem I needed to address, and they said that they don’t collaborate with ICE, and to talk to my attorney.”

In the check-in’s aftermath, Juan and Jaime didn’t want to go to school.

“They’re worried because they’re aware of what has been happening lately — that people who are immigrants are being grabbed without reason, investigated, and taken,” said Rojas, “They’ve seen the videos where [ICE] knocks on doors, breaks them down, breaks into cars, are aggressive. So they’re scared.”

Local service organizations that work with immigrants say there are more than 1,000 unaccompanied immigrant minors living in Massachusetts. And they confirm that the Homeland Security welfare checks are becoming increasingly common. Some like Stephanie McCarthy, vice president of Children and Families Services at Ascentria Care Alliance, say the department recently called her to ask for assistance.

“It was a question from Homeland Security of, we’d like to do these 'well visits.’ Can you gather people up? Those kinds of questions. Can we inspect them?” said McCarthy, who said her organization declined to share information, including addresses, about the minors they work with.

“Our kids are not animals and cattle that we’re going to gather to be inspected,” she said.

The state’s Department of Children and Families declined to answer whether unaccompanied minors in their custody have been visited by Homeland Security agents. But other organizations that work with immigrant children, including PAIR Project, say they’ve gotten words of similar visits in Massachusetts and other nearby states.

Local immigration attorneys say they too have heard from clients who’ve been visited by Homeland Security.

“They don’t have an order, they don’t have a search warrant or a judicial warrant or police order, and they are not [state] Department of Children and Families workers, so it’s kind of confusing on what kind of capacity they’re doing this,” said Karen Bobadilla, an attorney for De Novo, a legal services group that works with unaccompanied minors.

“My understanding is that the officers doing this are willing to talk to the attorneys, which is already great and is a win in my opinion,” said Bodabilla, “because they could easily just go in and if they have the enforcement authority, take everybody”

Other advocates note that while tracking unaccompanied immigrant children’s welfare is vital, the changes have them worried.

“We do believe it’s important that the federal government, through the Office of Refugee Resettlement, ensure that those children that have been released are safe, that their well-being is protected,” said Young of KIND.

But she says it’s not a job for Homeland Security.

“That’s a law enforcement check. That’s not a wellness check.”