The Black population of Greater Boston has grown, it’s more diverse than it’s ever been and the city of Boston is no longer its demographic epicenter. Those are three key findings in a new report out Thursday from Boston Indicators, the research arm of The Boston Foundation.

Researchers like Luc Schuster, who co-authored the report, say it’s important to understand how different groups within the ever-growing Black population have vastly different experiences.

The report says, in recent years, Greater Boston’s Black population has become one of the most diverse in the entire country, with “a wide range of ancestries from the West Indies region, Caribbean, and Africa.” And the report finds that only about a quarter of Black people in the region use descriptors that indicate they come from families of multigenerational, non-immigrant backgrounds, whereas nationally that figure is at nearly two-thirds.

“Afro-Latino population growth is a really key part of what’s been happening,” said Schuster, the executive director of Boston Indicators, pointing to an influx of Afro-Latino people from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. “We’ve seen, [in] both the city of Boston and the region of Greater Boston overall, the Afro-Latino population double in the last 20 years, just from 2000 to 2020.”

At-Large Councilor Julia Mejia — the first Afro-Latina to sit on the Boston City Council — was part of an earlier wave of immigrants from the Dominican Republic.

“When I came here in the ‘70s ... I came here at the height of the busing era. And what was really interesting to me was that that issue was Black versus whites,” Mejia said. “But Latinos in particular, we were not uplifted in that fight. And what I received was, ‘Go back to where you came from,’ from a lot of my neighbors that were white who did not want me to be here.”

She said racist attitudes still exist in Greater Boston, and that “we have a lot of work to do to heal from that.”

The report says that the Boston metro area’s overall Black population growth has been substantial — climbing to the 17th-largest metropolitan Black population in the country in 2020 with just over 480,000 people, after an addition of more than 100,000 Black residents since 2010.

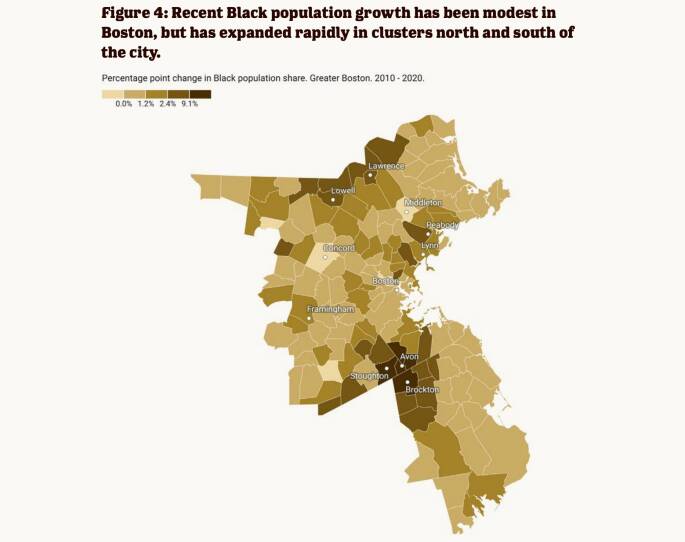

"From Hyde Park in the southern tip of the city of Boston ... connecting to Milton, then Randolph, Stoughton, and Brockton. There's a real kind of distinguished Black population corridor. Now that's a really new story for the region."Luc Schuster, The Boston Foundation

But the report says the usual move toward homeownership over the course of generations has been difficult for many Black households.

Schuster said that, since higher-income suburbs have been less welcoming to Black residents through both informal practices and formal efforts like exclusionary housing policies, a distinct Black community has formed in Massachusetts.

“You can almost identify a pretty clear connection of communities from Hyde Park in the southern tip of the city of Boston ... connecting to Milton, then Randolph, Stoughton and Brockton. There’s a real kind of distinguished Black population corridor,” he said. “Now that’s a really new story for the region.”

With the 2020 United States census, Brockton became the first municipality in Greater Boston to become majority Black, and the only such city in New England. To the north of the city, the region including Lawrence and Lowell has also had high growth from 2010 to 2020, the report found.

Schuster said that one of the most compelling statistics from the report demonstrating the growing internal diversity of the region’s Black population, was that nationwide, 11% of Black Americans are foreign born, while, in Greater Boston, that figure is practically four times as high, with 40% of Black residents being foreign born.

Mejia added that, as an Afro-Latina and a political leader, she wants to prioritize bridge building and coalition building within the increasingly diverse Black community of her city — particularly one where different populations are speaking different languages.

“I think that there’s an opportunity for us to build power along our shared experiences. And I think that that is where the opportunity really lies when we're looking at reports like this ... that we are seizing this moment to really look at what are the uniting factors here and how are we going to tackle those issues as a collective,” she said. “That’s real power building.”

Another major finding in the report was that, beyond Black residents facing structural racism in the state, there are nuances in how it plays out within the region’s increasingly diverse Black population.

“There are some Black subpopulations, especially Nigerian Americans, who have significantly higher levels of college attainment and tend to have meaningfully higher levels of income compared to multigenerational Black families,” Schuster said. “And [those families] unfortunately tend to have somewhat lower levels of college education and lower levels of median household income. So this just speaks to not treating all Black residents of the region as a monolith, and making sure we’re targeting interventions appropriately.”

The report concludes with a series of open-ended questions directed at advocates, political leaders and other decision-makers, including a question on reparations.

Proposals around the idea are advancing in several municipalities in Massachusetts, hoping to address the long-term effects of slavery and systemic racism in Black communities. In Boston, Mejia was one of the councilors who pushed for the city to create a reparations task force — which Mayor Michelle Wu appointed members to in early February. The group is tasked with studying how the city can right the wrongs that still hurt Black Bostonians, with a focus on descendents of people enslaved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Mejia said it was important to her that the process proceeds from the ground up.

“White dominant culture behavior is saying that since I'm the legislator, I’m the one that approved it. I’m the one who’s going to decide what reparations looks like. No, this has to be centered in community, and by the people who are living the realities,” she explained. “And that is what real leadership is about. It’s stepping to the side and creating space for other people to decide for themselves and define for themselves what reparations needs to look like in Boston.”