Michael Smith, 35, thought things were bad in March when the pandemic hit. He lost his job as a bartender, and his dream of buying a house for his young family disappeared. Smith, who lives in Revere, started collecting unemployment and spending down the money he and his wife had put away for the house.

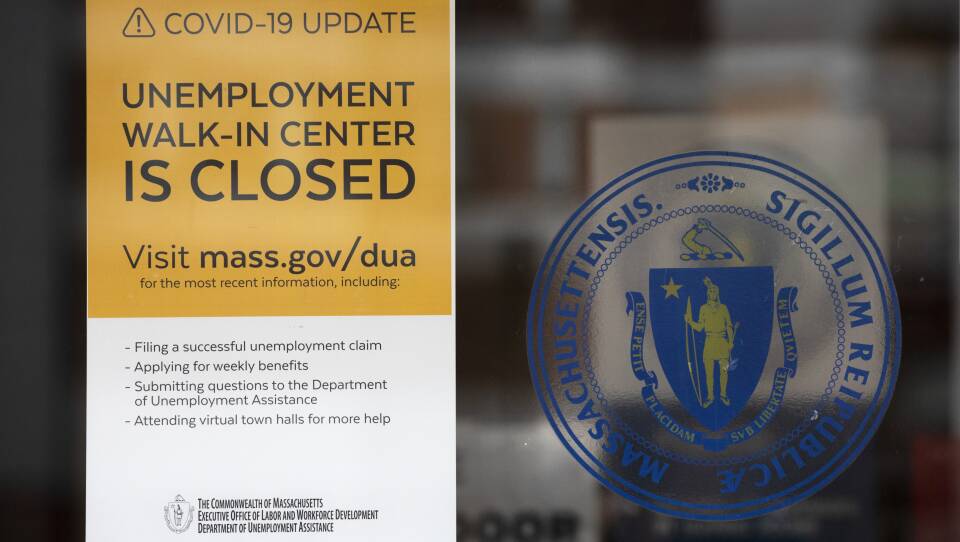

But when December arrived, Smith said, he realized things could get a lot worse. After finding a few months of short-term work, Smith’s hours were slashed, and he needed to file unemployment claims again. Yet, this time, he was not hearing anything back from Massachusetts’ Department of Unemployment Assistance (DUA).

For nearly six weeks he checked their online system daily. Until one day he went online.

“I saw that it said I was declared indefinitely ineligible,” he recalled. Soon, Smith learned he was supposed to pay back the $22,000 he had previously collected from DUA.

Smith's experience is not unique.

During the pandemic, Massachusetts has had among the highest unemployment rates in the country. But, experts say, that doesn’t include a whole slew of people trying to get unemployment assistance who are inexplicably unable to access the system. Legal aid groups say this group is surprisingly large and increasingly desperate.

Smith spent many hours on the phone with DUA before, he said, they determined his issue was simply a clerical error. Now, he’s waiting for a hearing — at some unknown future date — to resolve the situation. All this time, he’s had little to no income.

“It's been really tough. It’s been hard to balance what bills are getting paid this month or how much more can I put on this credit card this month,” he said, adding that he's grateful his kids get meals through their school even on the days when their education is virtual.

Legal aid offices say they have also been busy fielding calls from people seeking help navigating the DUA’s system.

“Our phones have been ringing off the hook,” said Samir Hanna, a clinical instructor at the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau.

“The problems appear to be quite widespread,” said Iván Espinoza-Madrigal, the executive director of the legal aid group Lawyers for Civil Rights. He doesn’t know the exact number of people affected, but Lawyers for Civil Rights has been getting a constant stream of calls from people who can’t figure out why they’re not getting any helpful information from the state.

Often, when they do figure out the source of the problem for a client, Espinoza-Madrigal said, it has to do with the state’s effort to verify a claimant’s identity. He said that in an effort to prevent fraud, the state has created an onerous identity verification process that has ensnarled many innocent people who are on the brink of running out of food or losing their housing.

The DUA declined an interview, but acknowledged in a statement that “address[ing] an unprecedented nationwide fraud scheme … may unfortunately slow the process of claimants receiving benefits.” The DUA’s staff has increased from 50 employees to 600 employees to help deal with the situation.

Still, Espinoza-Madrigal noted, the issues he’s seeing suggests the most basic functions at DUA aren’t happening smoothly.

“The state is not reviewing the documentation in a timely basis. They are often requesting supplementation without identifying what is missing or what is expected, leaving people in the lurch.” Espinoza-Madrigal said. “They are the ones creating the red tape.”

Smith spends a lot of his time either trying to contact someone at the DUA to see what he can do to start receiving unemployment assistance or trying to help others in the same predicament with whom he’s connected online.

“Yesterday alone, I answered 125 Facebook messages, just directing people for help and offering advice on how to navigate through the DUA system,” Smith said.

He said the stories are heart wrenching: a husband who is panhandling to help pay for his wife’s medical care or a mother who can’t afford fuel to heat her house.

“It is shockingly dysfunctional,” said Margaret Weir, a professor of political science at Brown University. She identified a few fundamental things going wrong. For starters, the state’s system is inundated. And, although the DUA in Massachusetts has modernized its IT system to deal with fraud, that hasn’t helped the unemployed.

“What studies of these modernized systems show is that they have been set up to be more suspicious of fraud and therefore to slow down the process and to deny more claims,” said Weir.

Over the years the unemployment system has become less and less helpful for the unemployed, Weir said. That’s partly because it is run state by state — and not nationally — and funded by a tax on businesses.

“Many states simply want to keep those taxes as low as possible in order to seem business friendly,” she said. So, the system is chronically underfunded.

In every recession since the system was developed after the Great Depression, Weir said, there’s been talk of reforming or federalizing the unemployment system. So far, nothing has happened. But, she said, things have been so bad during the pandemic that there’s a real chance things will change this time.

However, she acknowledged, future change is unlikely to help all of those people stuck trying to navigate the current system.