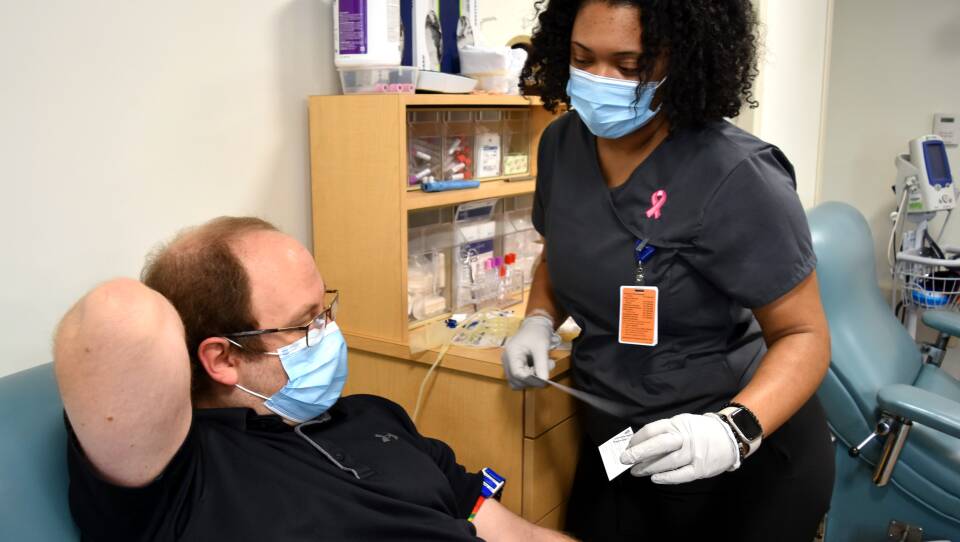

As infectious disease doctor Seth Bloom settled into a chair at the blood donor center at Massachusetts General Hospital recently, phlebotomist Jinneka Jackson asked him why he decided to make a donation.

"Well, I know there's been a blood shortage," Bloom replied. "And I'm pretty sure that I'm type O-positive, so I know that's really in demand."

More Local News

In January, that demand became so severe that the American Red Cross declared its first-ever blood crisis. Since then, hospitals have been scrambling to make sure they have enough blood for accident victims, surgeries, cancer patients and a range of other urgent needs. And some Massachusetts hospitals are starting to make plans for how they would respond if they were to find themselves without enough for all their patients who need it, a threat that is all the more real for hospitals who don’t have their own donor centers and rely entirely on outside organizations for their blood supply.

"The blood shortage is real, it's regional and national, and it is compromising patient care," said Dr. Robert Makar, director of the Blood Transfusion Service at Massachusetts General Hospital.

The problem is the pandemic. Donor events at places like schools and community centers have been canceled at a time when many don't feel safe gathering. The supply shortage wasn't as much of a problem in the initial pandemic surge, Makar said, because the hospitals were full of COVID patients who didn't require blood transfusions.

"In this most recent wave, the hospital is very busy," Makar said. "It's providing care to lots of non-COVID patients, many of them needing lifesaving surgery. And so the pace of blood use has been consistently high."

When the shortage first started getting bad in late December and early January, the Red Cross supplied MGH with about half the usual amount of O-positive red blood cells, Makar said.

"We were diverting all of our O cells to the operating rooms and to desperately sick bleeding patients," he said. "And so I know a lot of outpatients in the cancer center didn't get their blood, even though they were anemic, even though they would have otherwise gotten red cells."

MGH has enough blood to meet the current demand. But even so, the Mass General Brigham system is getting ready in case they get to the point where they just don't have enough. If levels ever get dangerously low, it will activate a new protocol announced earlier this month. The hospital will call upon a newly created Blood Allocation Team — made up of physicians with expertise in both critical care and ethics — who will determine how the limited supply should be used.

"The responsible thing to do is to make sure that we have plans in place so that if the blood collection services were to be unable to meet our demands for the care that we deliver, that we have an equitable, fair, evidence-based, rational way to look at how we use our blood products across our whole system," said Dr. Paul Biddinger, Mass General Brigham’s chief preparedness and continuity officer.

"For an emergency condition when you couldn’t anticipate what’s happening, our answer is not going to be ‘no, we're not going to offer blood,’" he continued. "But there's a point in the resuscitation where we might say, ‘This is threatening the care of other individuals who also need blood and we have to use less than we otherwise would have.’"

Biddinger stressed they're not at that point now, and they're trying hard to make sure they never get there. But they want to be ready, just in case.

"The blood shortage is real, it's regional and national, and it is compromising patient care."

Dr. Robert Makar, director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Blood Transfusion Service

To create a unified strategy in dealing with blood shortages and share best practices, the Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association says it plans to pull together a working group of member hospitals.

MGH made a push to increase the amount of blood donated at its own collection site in the hospital to try to fill the gap. The donor center is now supplying roughly half of the O cells the hospital uses, up from about 20 percent before.

Many of the donors they see are MGH employees like Bloom and Jamie Corbett, who works in the hospital's carpentry shop.

"Today, I'm donating platelets," Corbett said. "I try to do it, like, once a month. I started maybe like 20 years ago or so. This is like my 100th time, I guess, today. So it's a milestone, you know?"

There have been times in recent months when the American Red Cross has only been able to meet about 25 percent of hospital demand, according to Dr. Baia Lasky, the Red Cross's medical director.

"Really, hospitals to be in a comfortable place with their blood supply would like to be at a five-day supply," Lasky told GBH News. "And right now, the Red Cross — much of the time, for certain blood types — we're at less than a half a day's blood supply."

At Tufts Medical Center, they're doing everything they can to make sure every drop of available blood is used, said Dr. Jensyn Cone Sullivan, the hospital's associate medical director of transfusion medicine and cell therapy.

"We've worked very hard to carefully allocate that supply, so that included always being on the lookout and in communication with other area hospitals. ‘You have that unit, it's expiring today. Are you going to use it? If not, we'll take it. We can definitely use it,'" Cone Sullivan said. "So there's a partnership among hospitals to make sure nothing is wasted."

Tufts is one of many hospitals that are entirely reliant on outside blood suppliers like the Red Cross.

"This shortage, particularly, I would say, affects hospitals that don't have a donor center, like ours does not," she said.

Every time there’s a request for blood at Tufts, Cone Sullivan said her team now evaluates the patient to make sure they need a transfusion.

When to use blood, and how much to transfuse, is not always a given, said Dr. Vishesh Chhibber, the medical director for the transfusion service at UMass Memorial Health in Worcester.

"There's cases where it's unequivocal the patient absolutely needs the blood," Chhibber said. "[Then], there are times where within a certain zone, depending on the patient's symptoms and the patient's blood count, that there may be some discretion where some people say, 'OK, I think this patient would benefit from a unit of blood currently,' whereas someone else may say, 'Hey, you know, I think you can wait. Let's see how he does.'"

Like Tufts, UMass Memorial Hospital used to collect blood, but closed down its program before the pandemic. But Chhibber said the FDA's regulatory requirements — including expensive tests to check the blood for a range of diseases — became too much to keep up with.

"The bar continues to be raised and it just is more and more difficult to collect blood at hospitals and have it be basically something that's financially feasible," Chhibber said. "So I've seen many hospitals that had small blood collection programs basically do the same thing, where they're no longer collecting blood."

Hospitals and the Red Cross say the blood crisis could continue for months. And supply could get strained further in Massachusetts now that elective surgeries have started up again.

But as COVID-19 numbers continue to decline and life returns to something closer to normal, they're desperately hoping to see regular donors come back — and new donors show up. According to the Red Cross, 40 percent of the U.S. population is eligible to give blood, but only about 3 percent do.