The Presidential pardon power is as old as the United States itself. But few Presidents — if any — have thrown this constitutionally enshrined power into the spotlight like Donald Trump. In recent weeks Trump and his lawyers have even suggested he has the power to pardon himself.

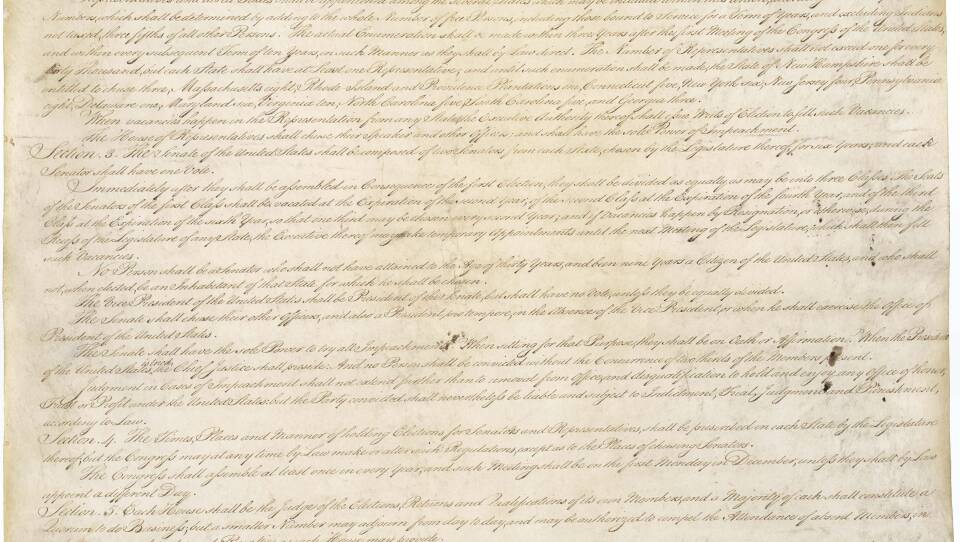

All this talk got me curious. Just why was the president given the power to pardon in the first place? As Harvard Law School’s Michael Klarman explained to me, it goes back to the 55 men who met in Philadelphia to create the U.S. Constitution.

"The main model they have is Great Britain," he explained. "There are lots of things in the Constitution that are directly derived from British practice."

Our two-house legislature is inspired by Parliament’s and many of the powers granted to the President were directly inspired by powers enjoyed by the crown in Great Britain.

"The King had the power to pardon, and that’s a power that most state governors would also have had," said Klarman. "I think it was pretty natural for [the framers] to assume that the President would have a pardon power."

And there is a reason why. The constitution was imbued with all sorts of checks on power. And in the pardon, the President was given one over the Judiciary.

"The criminal justice system might treat somebody too harshly [or] might make a mistake," said Klarman. "You want some institutional actor to have the authority to show mercy."

Despite the fact that many of the president’s powers were left vague in the Constitution, Klarman says that most of the framers agreed the president should indeed have the power to pardon. As for how broad that power should be? That was another story.

"A lot of opponents of the Constitution, the Anti-federalists, were very troubled by the idea that the president could pardon even in the cases of treason," said Klarman.

These Anti-federalists were no fringe group. They included men who were delegates at the Constitutional Convention, and prominent founding fathers like George Mason, Patrick Henry and Boston’s own Samuel Adams — all of whom had deep misgivings about the new Constitution.

"The Constitution was very narrowly ratified," said Klarman. "Two states — North Carolina and Rhode Island — originally rejected ratification. And in three of the five largest states the vote was so close it could have easily come out the other way."

Those states were Virginia, New York, and — yes — Massachusetts. To be clear, the Anti-federalists had gripes beyond the pardon power, but as the new constitution went to the states for ratification, it was among the issues that flared up.

"In New York, Anti-federalists actually wrote a constitutional amendment that would have limited the pardon power in cases of treason so that it could be essentially vetoed by Congress," explained Klarman.

In Virginia, George Mason railed against the notion that, under the Constitution as written, a treasonous-minded President could enter into a conspiracy, and simply pardon his co-conspirators. James Madison retorted that the Constitution also included a check on this broad presidential pardon power: Congress.

"The President does have the power to pardon, even traitors," said Klarman, explaining Madison's viewpoint. "But if he were to exercise that power in a way that he was basically trying to protect himself, you could impeach him."

The constitution would, of course, be ratified — at least in part because the framers left the powers of the presidency relatively vague, said Dr. Kathleen Bartoloni-Tuazon, historian and author of For Fear of an Elective King.

"Yes, they were kicking the can down the road a bit. And giving the responsibility for hashing out the Presidency to the first Congress and to subsequent Congresses," she said.

For more than 200 years, those powers have been defined and redefined numerous times. And Bartoloni-Tuazon says that each President is judged, partly, on how he chooses to interpret and employ their Constitutional powers.

"It’s up to the people in many ways to use the voice they have to determine how much change is permanent and how much is rejected or accepted, and then we move on to the next stage."

That voice takes can take many forms, but perhaps never more powerfully than when it's employed at a place that's also been with us since the very start of the American system of government: the ballot box.

We're always looking for story ideas here at the Curiosity Desk, and the best ones often come from you. What have you been curious about lately? Email me at curiositydesk@wgbh.org and let me know. I might just look into it for you.