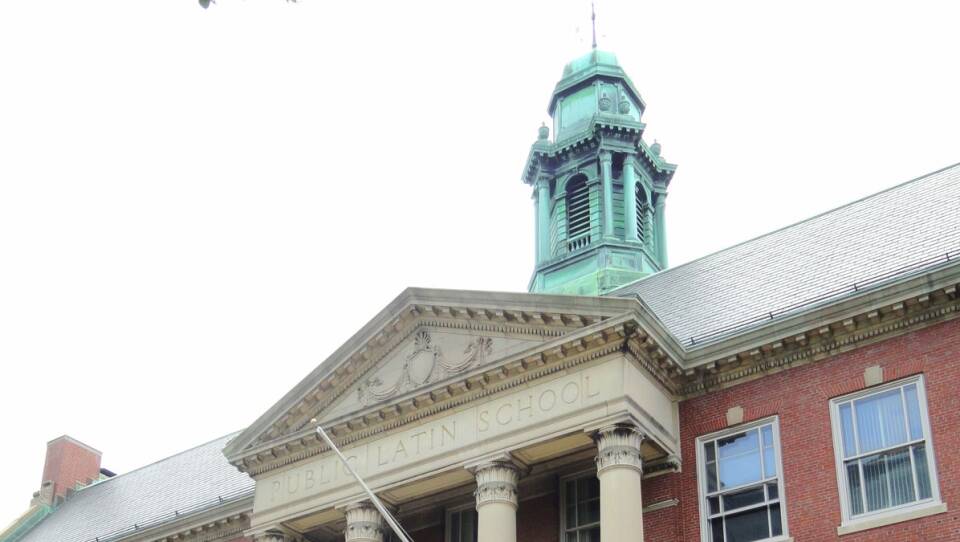

In Boston, voters can decide who is in charge of the nation’s nuclear arsenal, who the county’s chief prosecutor is, and who should be in charge of the state budget. What they can’t decide, however, is who sits on the seven-member committee that oversees the city’s massive public school system.

After Mayor Marty Walsh controversially put pressure on former Boston Public Schools Superintendent Tommy Chang to step down after three years, some are wondering if it’s time for the city to put the composition of the school committee back in the hands of voters.

“It is important for us as a city to have a conversation about whether an appointed school committee still makes sense,” Tanisha Sullivan, president of the Boston branch of the NAACP told The Boston Globe earlier this week. “Often people will say we need an appointed board to keep politics out of education. Anyone who thinks politics is out of education is out of touch. Having an appointed board is not going to change that. Further, I don’t think that is a reason for us to effectively strip residents and families of Boston of their right to determine who they want to represent them.”

Under the current system, the Boston School Committee is made up of seven people appointed by the mayor and led by a superintendent who is nominated by the committee. This effectively makes the superintendent also a mayoral appointee. Though Boston is the only city in Massachusetts that has an appointed school committee, according to former Massachusetts Secretary of Education Paul Reville, it was borne out of frustration with the dysfunction of having a committee made up of members elected by the public.

“When we had an elected committee, we had racial bias, we had huge deficits, we had tons of cronyism, we had poor performance in the school district, and we had pretty much constant turnover in the superintendency,” Reville said in an interview with Boston Public Radio. “How somebody can harken back to that as the good old days is beyond me.”

Joining Reville in his fear of returning to an elected school board are Walsh and former interim superintendent John McDonough, who said leaving the school committee in the hands of voters would be “one of the worst mistakes in the history of Boston.”

Noting this growing divide between groups like the NAACP and the Collaborative Parent Leadership Action Network and current and former government officials like Reville and Walsh, last Tuesday Boston City Councilor Annissa Essaibi-George, who chairs the Council Committee on Education, conducted a hearing where members of the public could provide city officials with their opinions of how the school committee should be chosen.

“There has been a lot of turmoil about how decisions about BPS are made,” Essaibi-George said. "I wanted to give people a chance to get their voices heard and on the record, so that any changes are responsive to the families and professionals who understand the system from the inside and are most affected by School Committee decisions."

At the hearing, some contended that while in the past the School Committee may not have operated perfectly, those risks don’t merit the choice of who sits on the committee being taken out of the hands of voters.

Reville disagrees. According to him, the mayor-appointed school committees have not only been more representative of the 56,000 students in the district, but that by giving the mayor more control over the school committee, the public still remains a check on them.

“An appointed committee puts the mayor in the driver’s seat, and that was the purpose.” Reville said. “[Now] the voters [can] hold the mayor accountable for something that consumes the lion’s share of the city’s budget, and [for] the performance of the education system.”

Members of the public, however, don’t see it the same way. At a hearing led by Essaibi-George on Tuesday, members of the public resoundingly told the City Council Education Committee that they want the school committee to be accountable to more than just the mayor.

“Why are Bostonians not worthy of naming their own school committee?” John Drew, president of the nonprofit Action for Boston Community Development said at Tuesday’s session. “It baffles me because we would be stronger with a public school system with all hands on deck.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated Boston City Councilor Annissa Essaibi-George's stance on whether the city's school committee should be elected. The post has been updated.