From youth sports to pro football, concussions are a big concern. Get one, you need rest. Avoid them and — the thinking is — you’re good to go.

But researchers have long suspected that you don’t need a concussion to develop the degenerative brain disease Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy or CTE. Now they have proof.

It comes from a hidden-away lab deep within the campus of the Boston University School of Medicine where Dr. Lee Goldstein has developed a way to recreate in lab mice the kind of force faced in two of the most common situations linked to CTE: battlefield blasts and football tackles.

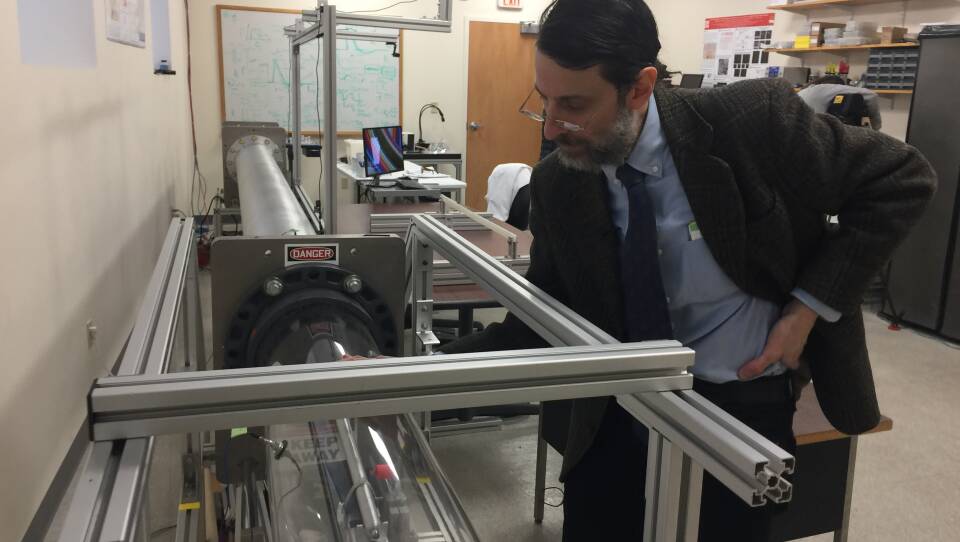

First, the tackle. A table-top machine delivers the mouse-equivalent of a flying football tackle. It features helmet-like padding to protect the mouse’s head.

The mice tested in this machine all got concussions. Some were mild; some were complete knock-outs. After the hit, their brains showed the kind of damage that causes CTE.

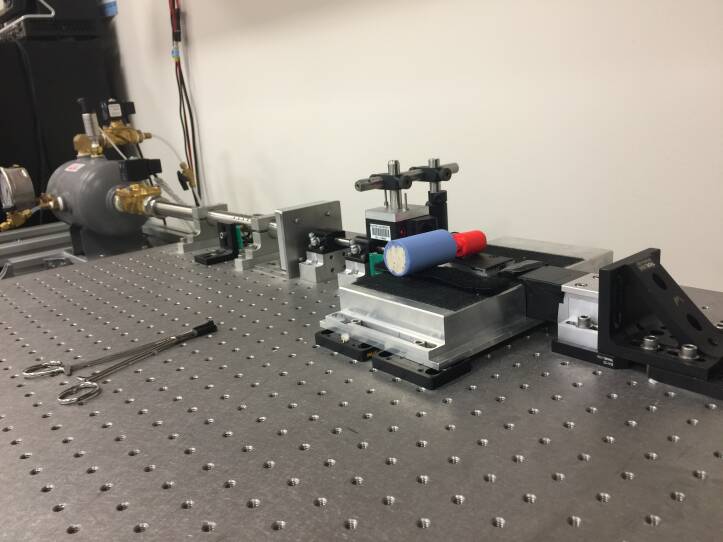

Goldstein used a second machine, a 30-foot stainless steel tube called a blast tube shock, to recreate the mouse-equivalent of an improvised explosive device. Mice tested in the tube also developed the beginnings of CTE, but never got concussions. Goldstein’s conclusion: “It’s the hits that cause CTE, not the concussion.”

He says his experiments prove concussions are a symptom of CTE, the same way a hacking cough is a symptom, not the cause, of lung cancer. He says just as someone could have lung cancer without a hacking cough, it’s possible to develop CTE without ever getting a concussion.

“One of the most important findings about this work is not about concussions. It’s about the hits that are not concussive, the sub-concussive hits,” he said. “Those are the ones we’re most worried about because those are the ones that happen most often.”

Goldstein’s study, published in the journal Brain, also includes research done on four teen-age athletes — all of whom shortly before they died suffered a hit to the head, but not a concussion. In all four cases, the brains off the teen-age boys showed evidence of the early signs of CTE.

“Right at that moment, right when they’ve had that injury,” he said, “we’re already starting to see, it’s kicking off that process that will lead to CTE years to decades later.”

This latest research helps explain earlier findings that among former football players diagnosed after death with CTE, about 20 percent had no known history of a concussion. It also calls into question protocols that mandate coaches, especially in football, pull players for concussions, but not necessarily for repeated hits to the head.

Goldstein says his research proves those smaller hits — especially when they come close together and especially in kids — damage the brain. But even as his work sheds light on the risks of sports like football, there’s a question he and other researchers have yet to answer: why some athletes who play contact sports never develop CTE.