Ten minutes before the patients arrive, walkie-talkies start buzzing. Clusters of technicians and interns, dressed in scrubs, snap to attention. Carts loaded with medical equipment are wheeled into place.

Suddenly, the patients are here — and they’re in rough shape. Some, when prodded with thermometers, twitch an arm listlessly. Others are so comatose they look completely dead.

But these patients aren’t being unloaded from ambulances and wheeled in on gurneys. They’re packed in cardboard banana boxes lined with towels. And they’re not even human, though you’d be forgiven for thinking so, given the careful medical attention they’re receiving.

They’re sea turtles.

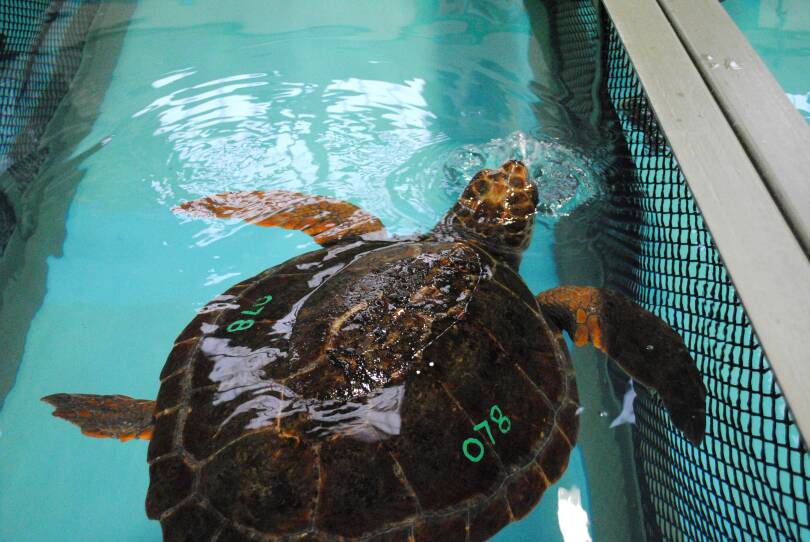

Biologist Adam Kennedy is working the floor today at the New England Aquarium’s Animal Care Center, a state-of-the-art marine animal rehab facility nestled in Quincy’s old shipyard. Two turtles have just come in, rescued off the beaches of Cape Cod by volunteers, and he’s giving them a preliminary check-up. One turtle is completely motionless, and Kennedy directs it to an ultrasound machine to check for a heartbeat. The other flaps its fins sluggishly when poked — a promising sign. He writes an identification number carefully on its shell.

Kennedy wasn’t always in this line of work. Originally a programmer in the pharmacy business, he started volunteering with the aquarium back in 2002, hoping to work with seals and whales. But it was the turtles and their unusual plight that won him over.

“Like a lot of folks, I didn’t really know there were sea turtles in Cape Cod Bay,” he said. “Who would think a reptile would be in Cape Cod Bay?”

Turtles come to Cape Cod for the same reason we do, explains Tony LaCasse, the New England Aquarium's media relations director: “The restaurants are good, the seafood is good.” They travel up north from the Gulf of Mexico in the summer to feast on the crab off the Cape Cod coast, when the water is in the balmy 60s or 70s. But when the temperature starts to drop, the trouble starts.

Come September, as the water begins to cool, the turtles feel the urge to migrate back down south. But blocking the way to the south and east is the arm of Cape Cod’s peninsula. Many of these turtles are babies and inexperienced, unable to intuit that they must swim north, past Provincetown, before they can get back out into the Atlantic. Many become trapped in the bay.

Turtles are reptiles and cold-blooded, which means that their inner temperature fluctuates with the temperature of their surroundings. As the water chills to a frigid 50 degrees or less, these turtles, over time, become seriously hypothermic, or "cold stunned." Their metabolisms slow, and so do their heartbeats (some even as slow as one or two beats per minute.) They become so sluggish that they’re no longer able to catch food and feed themselves. Then they wash up on the north Cape’s beaches — in recent years, hundreds and hundreds of them — some covered in algae and even barnacles like you’d see on rocks and shipwrecks.

“The average sea turtle somebody would find on the Cape, particularly by Thanksgiving on, if you discovered it, you’d probably think it was dead,” La Casse says.

The New England Aquarium believes Cape Cod is the only place where these annual mass turtle strandings occur in the entire country, maybe even the world. And a unique problem requires a unique solution, which is where the turtle hospital comes in.

The Care Center is filled with tanks, some outfitted with glass along the sides so you can see turtles zipping through the water. In one is a handful of three-or-four-pound Kemp’s ridley sea turtles, the rarest and most endangered sea turtle species. Most turtles that wash up on the Cape are Kemp’s ridleys.

In another tank is a hulking loggerhead turtle — named so for its large, thick head and neck — lumbering solo. These can grow to be hundreds of pounds, which can make for a challenge when they need medical attention or there are more than one of them. (Loggerheads get aggressive with other loggerheads, so staffers sometimes have to separate the snippy ones with a few strategic swipes of a netting pole.)

Today, interns Kathy McCarthy and Sarah DiCarlo had to hoist an 80-pound loggerhead over to the X-ray labs. “How do you lift something like this?” they’re asked. “With your legs, not your back,” DiCarlo quips.

Since the turtles become hypothermic over the course of weeks, the Care Center takes a similar approach to warming them back up again: they do it over time. A series of tanks are heated to different, gradually warming temperatures (for example, 55 degrees, then 60 degrees, then 65 degrees, and so on) and turtles move from one to the next when they’re ready. Warming them too quickly creates a fertile atmosphere for the pathogens that have loaded on board while they’re stranded, and these turtles — whose immune systems have been compromised by their hypothermia — wouldn’t be able to fight them off.

In the meantime, they’re monitored closely. They get X-rays to check their lungs for pneumonia, are administered antibiotics and antifungals, get regular exercise, and are encouraged to build an appetite back up. The goal is not only to rewarm them, but to nurse them back to full health.

“It’s both rehab and convalescence,” La Casse says.

This hospital was built to comfortably house around 100 patients, which in the past, when their average intake was around 70-90, was more than enough. But that’s changed.

In the last five years, their average has ballooned to over 300. One year, they had 700. When the numbers get that high, the Care Center must find other places for the turtles to complete their rehab, sending them to aquariums all over the east coast.

The influx points to both the Care Center’s successes and signs of a changing climate around Cape Cod. More turtles means their populations are growing and stabilizing. On the other hand, it points to the fact that the seas around the Cape are warming up — according to some estimates, the Gulf of Maine is one of the fastest-warming bodies of water in the world — which means that turtles will venture further and further north to feed on crab.

“In 30 or 50 years, our ecosystem could look much more like what you’d find off the Maryland-Virginia coast,” La Casse says. “That also means that the cold temperate species are not going to be able to survive here as well, or maybe not at all.”

New England staples, like lobster, could become rare or even disappear from the region.

When animals move into areas that don’t have rules in place to protect them, tragedy can strike. That’s what happened when North Atlantic right whales began moving outside of protected areas to search for food: many were entangled in fishing traps and killed, which decimated their already-fragile population.

For Kennedy, protecting these vulnerable species from human damage is one of the concerns that drives his work.

“A lot of what has been done to the sea turtles has been done by humans,” Kennedy says. He hopes that there will still be Kemp’s ridleys and loggerheads when his three young sons are his age.

“We’ve done so much to this planet,” he continues. “Every little thing we can do to help, I think we should. “