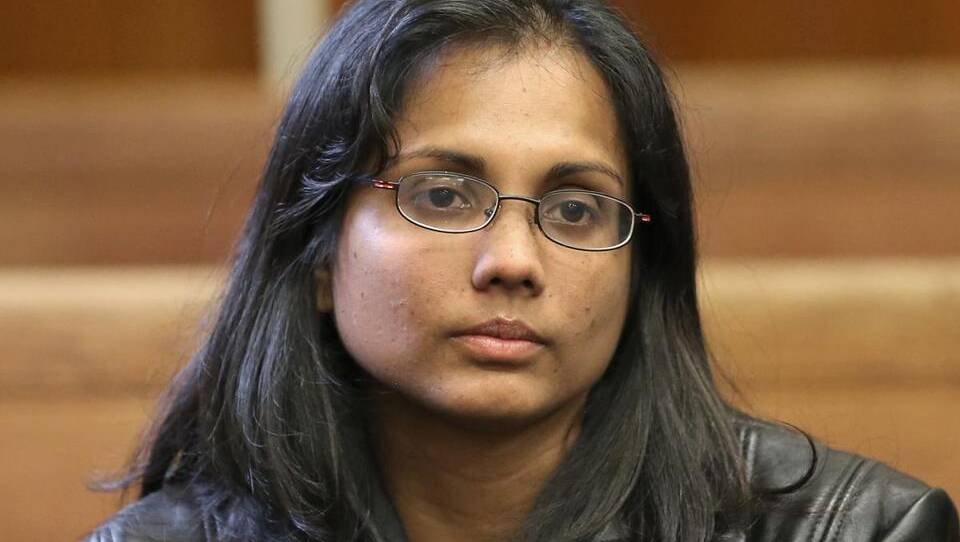

Today marks the end of the time period imposed by the Supreme Judicial Court in January requiring prosecutors to make final decisions about the estimated 24,000 Massachusetts criminal drug cases tainted by the misconduct of Annie Dookhan, a state chemist whose fraudulent activity at the Hinton Crime Lab in Jamaica Plain came to light more than four years ago. Prosecutors must decide which of the affected cases should be dropped and which ones might be retried. No matter what happens, today promises to represent one of the largest, if not the largest, mass dismissal of criminal cases in American history.

I anticipate prosecutors will dismiss almost all the cases. In the SJC opinion, Chief Justice Ralph Gants strongly hinted that prosecutors should drop the bulk of the cases or otherwise run the risk of overwhelming the system, especially our public defenders’ office. More notably, Dookhan’s track record of fabricated test results and failure to follow protocols undermines virtually all these cases. How could prosecutors prevail in, say, a cocaine possession case where there is an unanswerable question at this stage about whether the seized evidence was in fact cocaine? Absent other pieces of evidence (beyond the drugs themselves) that implicate the defendant, each case has what I like to call “built-in” reasonable doubt.

The notion that criminal defendants may only be convicted upon proof beyond a reasonable doubt is a bedrock principle of our criminal justice system. For one thing, the reasonable doubt concept protects all of us from the potentially awesome power of the state by forcing law enforcement to dot its I’s and cross its T’s before proceeding to trial. What’s more, the concept reflects the eighteenth century maxim advanced by British legal commentator William Blackstone that it’s better to let ten guilty go free than to convict a single innocent. It’s fair to say that some guilty Dookhan defendants will have their convictions erased. In my view, this is a desirable trade-off. We must safeguard the innocent from wrongful convictions and shield all of us from government overreaching even if the cost is that some factually guilty people evade punishment.

The reasonable doubt principle surfaced last week in the trial of former New England Patriot Aaron Hernandez for shooting two men to death in the South End. The jury acquitted Hernandez of homicide charges after lengthy deliberations. The prosecution’s murder case was riddled with reasonable doubt. The only person who could point definitively to Hernandez as the triggerman was Alexander Bradley, his former friend and companion on the night of the shooting who testified under an immunity agreement. The immunity deal rendered Bradley’s credibility inherently suspect given that he had an incentive to implicate Hernandez, namely, to avoid any criminal responsibility for his own role in the crimes. We may never know whether Hernandez or Bradley fired the fatal shots that night. What we do know is that the jury held the prosecution to its burden of proof. In that sense, justice was served. Maybe not justice in a moral sense — for there is a good chance that a murderer escaped punishment — but justice in the eyes of the law.