Majorities in many ethnic, identity and racial groups in America believe that discrimination exists against their own group, across many areas of people's daily lives, according to a poll from NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The poll asked a wide range of questions about where Americans experience discrimination — from the workplace to the doctor's office — and people's perception of it. The groups polled include whites, blacks, Latinos, Asian-Americans, Native Americans and LGBTQ adults.

White Americans are among those who feel their group is discriminated against, with 55 percent saying discrimination exists against whites in the U.S. today.

These results are part of a large national statistically representative survey of 3,453 adults from Jan. 26 to Apr. 9.

We will be releasing the full results of the poll over the next several weeks, starting Tuesday with results from the survey of African-Americans. We will highlight and analyze the particular acts of discrimination that each group experiences.

The African-American results, in 802 adults, provide insight into the historically high levels of discrimination blacks have faced since arriving in America. These experiences happen across a broad range of situations: interacting with police; applying for jobs or seeking promotions; trying to rent an apartment or buy a home; or going to a doctor or health clinic.

The findings on African-Americans have a margin of error of plus or minus 4.1 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level.

The perceptions of discrimination are not primarily based in actions by institutions, as some might expect. "Most African-Americans believe that discrimination is due to the attitudes of individuals that they interact with," says Robert Blendon, the poll's director and professor of policy and political analysis at the Harvard Chan School. "A smaller share believes it's actually government or institutional policies."

Fear of discrimination, possibly triggered by past encounters, plays out in different ways. We found that this fear significantly influences people's decisions whether to seek medical care, to call the police when in need, and even whether to drive or attend social events. Nearly one-third (32 percent) of African-Americans polled said they have personally experienced racial discrimination when going to the doctor or a health clinic, with 22 percent avoiding care out of fear of discrimination.

"If someone is avoiding seeking medical care out of fear of discrimination, they're at risk of going undiagnosed for serious conditions," says Dr. Richard Besser, president and CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. "We know that repeated stress from discrimination and racism can actually make some of those conditions more likely in the first place and shorten lives."

And repeated stress comes from many kinds of discrimination and the fear it engenders. Numerous studies have shown that African-Americans are more likely to be stopped by police compared with other racial groups. In the poll, 60 percent of people told us that they or a family member have been unfairly stopped or mistreated by police because they are black.

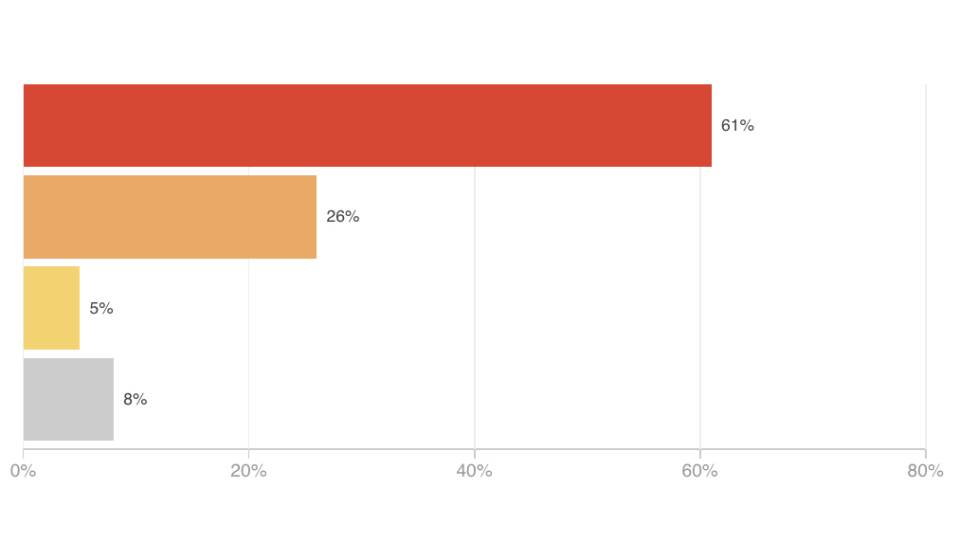

That has consequences for them personally and across society — 31 percent of poll respondents say fear of discrimination has led them to avoid calling the police when in need. And 61 percent say police are more likely to use force on a person who is African-American than on a white person in the same situation.

Where people live can make a big difference, too. Our survey found that 64 percent of blacks live in non-majority-black areas. For these people, perceptions of local discrimination, opportunity, police and government and community environment were generally better when compared with majority-black areas, sometimes by wide margins.

Our poll found substantial numbers of African-Americans who say they have been slurred or have been the target of insensitive or offensive comments or negative assumptions. A story later in our series will explore the split by income and gender in the chart below.

Persistently higher premature death rates in blacks compared with whites was one of the issues that inspired this poll and series. The most recent statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that gap at 16 percent, even though it has narrowed since 1999, when death rates for blacks from all causes were 33 percent higher than whites.

Many factors play into the gap, including a considerable drop in crime rates involving African-Americans over that period and improved access to medical care for many people. What we're trying to explore with our "You, Me and Them" series and poll is how the stress-inducing experiences of discrimination in everyday life affect health.

"Over 200 black people die prematurely every single day in America, in part because of racism in society," says David Williams, a professor of public health at the Harvard Chan School who has pioneered work in the field of racial disparities in health care. "This poll helps us see where we need to take action to address the problem."

Copyright 2017 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.