When it comes to breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier, most people know the name Jackie Robinson.

Robinson became the first Black player in the majors when Brooklyn Dodgers manager Branch Rickey signed him in 1947. The racism and hostility that he encountered is well known.

“But there are men, both Black and Latin, who suffered the same plight as Jackie,” Frank Jordan said recently as he walked through an exhibit on the pioneers of baseball integration. It was Jordan’s effort that brought the traveling exhibit to Boston.

”They had their struggles, but also they had their rewards,” Jordan said. “They had an opportunity to show the world how good they were.”

“Breaking Barriers: From Jackie to Pumpsie 1947-1959” opened at Emerson College on Juneteenth and runs through August 4. Created by the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, the traveling exhibit tells the stories of the Negro Leagues and the athletes, many of whom are less known, who integrated baseball over the course of 12 years. A virtual version of the exhibit is available online.

Jordan pointed to a black-and-white photo of a baseball player in a New York Giants uniform.

“This gentleman here, Monte Irvin, they said he was the guy that Branch Rickey wanted before Jackie Robinson,” Jordan said. “But he went into the military, served in the Army, and fought in the Battle of the Bulge [in World War II].”

When Irvin came back from the war, Jordan explained, he had “shell shock” — as PTSD was known at the time — and wasn’t ready for the attention of the major leagues.

“Two years later, he signed with the New York Giants in 1949 and went on to play,” Jordan said. “And he also went into the Hall of Fame. These are names you never heard of, but they were pioneers, too.”

More Local News

Those groundbreaking players include Larry Doby, who became the first Black player to integrate the American League in 1947 when he joined the Cleveland Indians, and San Diego native John Ritchey, who integrated the Pacific Coast League when he joined his hometown team San Diego Padres in 1948.

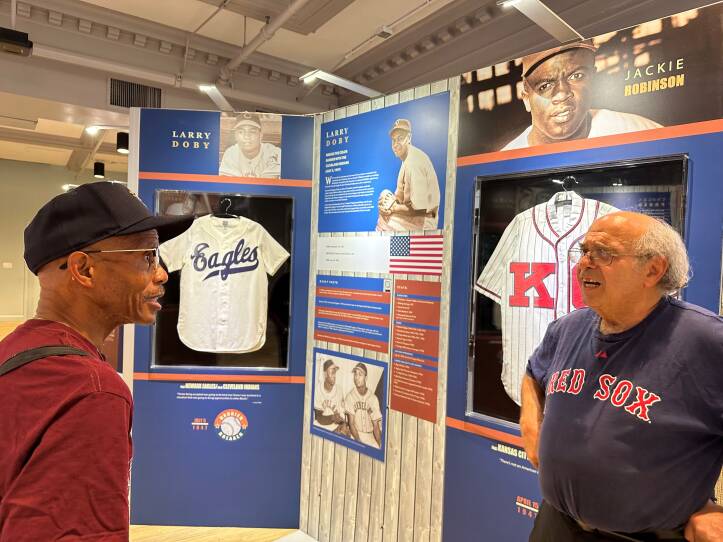

It’s the kind of exhibit that creates conversations, especially between baseball history enthusiasts like Curt Spiller of Encinitas, California and Norm Ginsberg of Newton, who met each other at the exhibit last week.

Ginsberg knew some of the history here, he said, but there’s still a lot to learn.

“More than baseball fans, I think it’s important for the population in general to see this. I mean, how far the country has gone,” Ginsberg said.

For Spiller, who is Black, that progress feels more vulnerable.

“The society we have right now could very easily slip back to the days before this,” he said.

An exhibit like this feels especially important now, Spiller said, with African American history curriculums being targeted around the country. Politicians like Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis have taken aim at the College Board’s AP African American Studies curriculum, claiming that the teachings were not “historically accurate.”

“We have people who don’t want us to know this history,” Spiller said.

For Jordan, the racially fraught history of baseball is something he’s lived with his entire life. The 76-year-old grew up in Georgia and his father, Luther, played for the Augusta Bears — a team in the Negro Leagues.

“It was sort of like the second level of the B team, like a regional group,” he said.

Jordan said he’d sometimes travel with the team to games.

“Friday evening, they got together, packed the bus, and that Saturday played a doubleheader. And that Sunday they would play a game,” he remembered. “And the local churches would let their members out early so all of them could go to the ballpark.”

For three games, the 20 teammates would split a paycheck of $80.

“And they took spare parts in case the bus broke down,” Jordan said. “Spare radiator, spare water hose and extra fuel. That was the life of many of the Negro League teams because they could not get any help on the road.”

As a special advisor to the Boston Red Sox, Jordan worked to bring the exhibit to Boston.

“Of course, you got Pumpsie Green here,” Jordan said, pointing to the exhibit on Green. He was the first Black player to join the Red Sox roster. Green played in minor league affiliates in the Red Sox farm system beginning in 1955, but didn't make his historic major-league debut until 1959, making the Sox the last major league team to integrate. It had been 12 years since Robinson joined the Dodgers, and in that time, nearly 120 Black and Latino players were brought up to the major leagues.

It’s a difficult legacy the team continues to grapple with. Over the years since then, Black athletes have said Boston is the hardest place to play, with players like CC Sabathia, Torii Hunter and Adam Jones facing taunts on the field.

“Yes, Boston has a history,” Jordan acknowledged. “Everywhere has a history. [Boston] should not be singled out as the worst city. It's a city that’s in progress to change the dynamics.”

As part of that change, Jordan’s been working to broaden access to baseball in Boston. In 2002, he co-founded the Boston Area Church League in Dorchester, teaching baseball to kids, with local police officers serving as coaches and mentors. Jordan says they hope to have 400 kids play this summer.

“We teach these kids the fundamentals,” Jordan said. “How to pitch, how to catch, how to throw, how to hit. More than that they learn how to respect each other, how to become a team and how to create friendships that last a lifetime.”

Through baseball, he said, we can understand a lot about this country’s past, and its future.

“I can’t do anything about what happened yesterday. Nor can you,” Jordan said. “But we can sure make sure we don't make the same mistakes today. And we learn from the mistakes and the successes.”