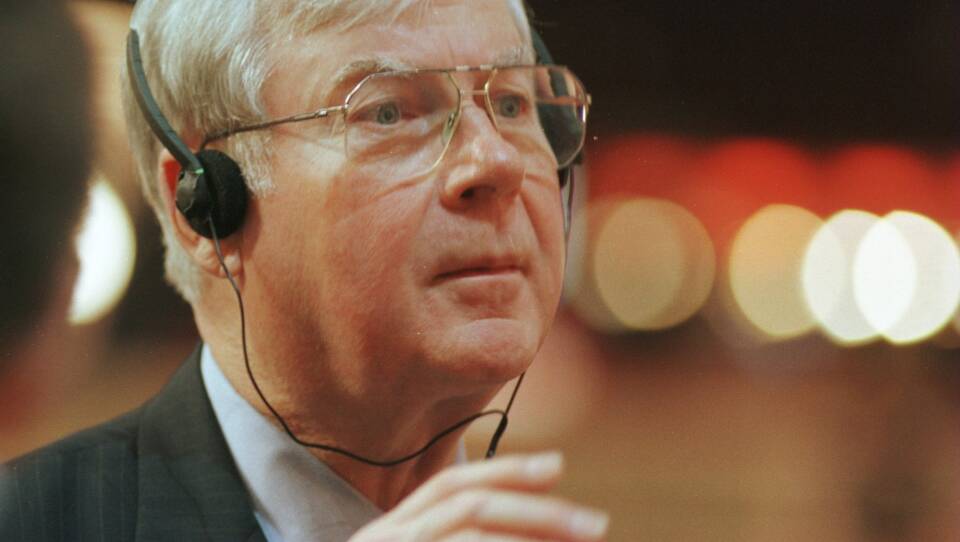

Last week we lost one of the great practitioners of American politics. To paraphrase the tag line from the 1960s TV drama Naked City, there are 8 million hilarious and inspiring stories in American politics. James B. King stars in nearly all of them.

As a teenager Jim King volunteered for John F. Kennedy’s 1952 Senate race. His career included working for all three Kennedy brothers and for Sen. John Kerry, too, becoming the premier advance man in American politics, serving as the guru for generations of Democratic political operatives, leading the Office of White House Personnel, Chairing the National Transportation Safety Board, and serving as Director of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), a VP at Harvard and at Northeastern. There are many great resumes in Washington. But very few of those resumes are linked to an individual who was a sage of American politics, who embodied the power of laughter, who personified commitment to public service and treated everyone he met with the respect and dignity all human beings deserve.

Jim forgot more about American politics than any of the rest of us— his students in politics — would ever learn. He could teach you every trick in the book of political advance. He could walk into a bar in any American town and by the time he finished one beer he could tell you what issues move the locals. If his candidate had an unconscious habit of grabbing his privates (true story) Jim could figure out how to situate the spouse on the campaign trail so she could stand next to her candidate husband and hold the offending hand when he was on a podium.

Oh, the stories—stories told by Jim and stories told about Jim. There was the time he worked on the 1967 campaign to elect the first African American, Richard Hatcher, as mayor of a large American city. Hatcher was running in Gary, Indiana to unseat a corrupt, political machine. The Hatcher campaign had no poll watchers to protect against ballot box stuffing. The only asset Jim had to work with was a large numbers of volunteer college students. Jim scoured the local Goodwill and Salvation Army stores to find black suits, sunglasses and black fedoras to dress his student to look like FBI agents stationed outside polling places. Needless to say, there were no stuffed ballot boxes that Election Day in Gary and Hatcher beat the machine.

For Jim politics was not about self-aggrandizement. The first time I attended a Jim King staff meeting at OPM, he nixed the idea of getting a puff piece on his career published in the Washington Post. He told us that the way to get things done in DC was not to seek the spotlight for yourself but to look for ways to give credit to others.

I will never forget a House Appropriations Subcommittee Hearing in the spring of 1995. The new GOP majority in the House and the Clinton Administration agencies were often at loggerheads and the OPM staff was concerned that our budget was about to be slashed. Jim gave a typical Jim King opening statement where he outlined the importance of improving and protecting the civil service while using self-deprecating humor to make his points. The Republican subcommittee chair, Representative Lightfoot of Iowa then opened his remarks by praising Jim as one of the rare and refreshing breed of Washington officials who take their mission seriously but do not take themselves so seriously. Our budget requests were not slashed that day.

But what made Jim particularly special was his humanity. Jim never forgot where he came from— Catholic, working-class, Ludlow Massachusetts, Irish, Democrat. As proud as he was of his roots, he believed in giving the deepest respect and kindness to everyone he met, no matter their roots.

While working for Jim at OPM in 1994 my father unexpectedly died. I went to see Director King to seek his permission that I be allowed to take my lunch hours off (if it did not conflict with a congressional hearing) so I could attend a Jewish service and say the kaddish prayer—the Hebrew prayer one says for a deceased loved one. Jim, to my initial surprise, answered me by saying, “no, Ira you do not have my permission.” He then paused a moment and said, “you do not have my permission but you do have my order— you are to go every day to services and honor your father. And I do not want to ever see you on the job during that time of the day no matter what else is going on.”

To quote William Shakespeare, we “shall not look upon his like again." But we can all take lessons from his life to defend and strengthen the American democracy he loved.

James B. King died Sunday, June 8, 2019 while working at his home in Rockport, Mass. He was 84.

Ira Forman was a college freshman in the winter of 1971 when he enrolled in Jim King’s study group “Nuts and Bolts of Campaign Politics” at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics. In the 1990s Forman served then-Director King in OPM’s congressional relations office.