On the toasty morning of July 15, 1891, four middle-aged women met at Rowes Wharf in Boston, boarded a boat and set sail for one of the outermost harbor islands: Great Brewster.

At the time, its rugged landscape was home to little more than a smattering of structures — including "huts of refuge" for potential shipwreck survivors — and a single cow that roamed the island.

The women were leaving their husbands, children and responsibilities behind for more than two weeks in search of adventure and the joy of female friendship.

Their provisions included food, art supplies, literature and one leather-bound journal.

And it’s that journal that, over a century later, mesmerized Boston-based author Stephanie Schorow when she came across the volume in Harvard’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

“But there was one big problem with it,” Schorow said. “We knew the identity of one of the women in the diary. But we didn’t know the other three women. Now, we had their photos — but we did not have their names.”

The journal detailed the cold corned beef they ate and the poetry they read by moonlight. It recorded the tides and the flora of the island.

Photographs, a novelty back then, showed their rustic cottage. It was the site where they pitched a hammock and hoisted an American flag — which, at the time, had only 43 stars.

They adopted their own playful language — a mix of Shakespearean and swashbuckler — sprinkling in the word “Ye” for flair.

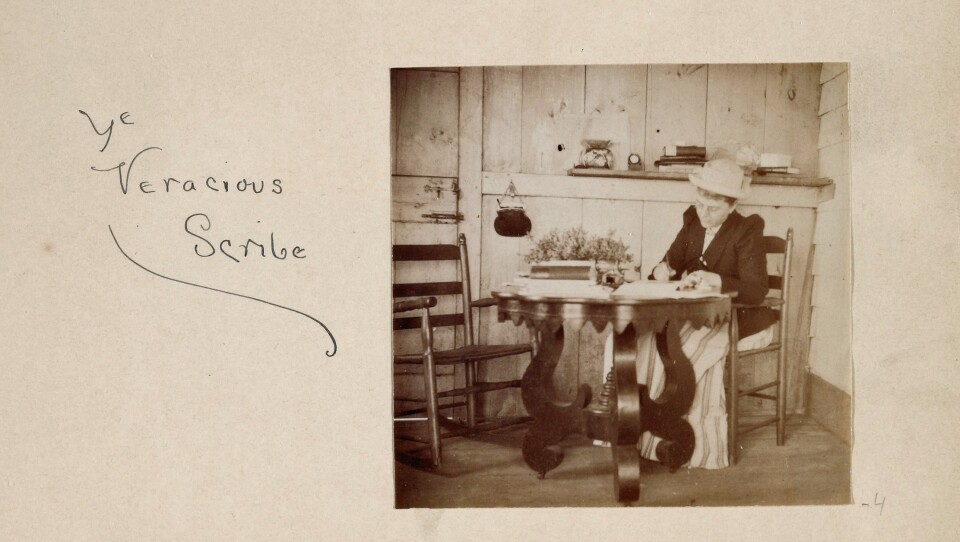

“The women in the journal were only identified by their nicknames: The Autocrat, the Aristocrat, the Acrobat and the Scribe — which, when you get down to it, are kind of weird nicknames,” Schorow said.

One of the women, whose moniker was “Ye Veracious Scribe,” had already been identified as Helen Augusta Whittier, a Lowell resident whose name was found on a handwritten note in the journal.

Schorow tried to focus on her other projects: she’s the author of several books on Boston’s history. But the journal — and the peculiar women who created it — kept returning to her mind, and the hunch that its creators had their own contributions to make to modern-day scholarship.

A modern-day band of amateur sleuths

Schorow made a few phone calls to solicit help identifying the women.

A collection of about 10 people, almost exclusively older women, stepped forward to volunteer their research skills in 2020, when the pandemic kept them all home.

Over Zoom and emails, they began by transcribing the journal, which, due to the abundance of “ye”s and antiquated penmanship, wasn’t simple.

“They don’t teach cursive to students anymore. But we’re old gals. So we wrote in cursive. We could decipher it,” Schorow said. “But even then, there were some parts we’d say, ‘I don’t know what they’re saying here.’”

Once the journal was transcribed, the next task was to distinguish which woman — their names still unknown — wrote which entries.

One of the investigators, Allison Andrews, had previous experience evaluating handwriting and cataloguing photographs. She noticed that some of the writers used periods, and some wrote with a dash.

The group stitched together census records, newspaper clippings and public records from genealogy websites.

And now, after years of research, they feel confident they have identified all four women:

- Helen Francis Ray French was the “Ye Autocrat.” The daughter of a clothing manufacturer in Lowell, she later ran a lodging house with her husband.

- “Ye Gentle Aristocrat” was Sarah Elizabeth “Lizzie” Dean Adams, a founding member of two humanitarian clubs in New England.

- “Ye Artistic Acrobat” was Isabella Coburn, a well-known painter who studied at the New England Conservatory of Music and what’s now the Massachusetts College of Art. Coburn died of heart failure four years after the trip.

- And the trip’s ringleader, nicknamed “Ye Veracious Scribe,” was Helen Augustua Whittier. She never married and ran her family’s textile mill in Lowell, before founding a Boston newsletter for women and becoming a leader in New England’s women’s suffrage movement.

Why sail to Great Brewster?

“We can only suppose that they were trying to say to the world, ‘We can do it ourselves. Women can do it ourselves,’” Schorow said.

Journal entries describe how they foraged and fished: After dinner, 2 of them, with rubbers, pails and spoons, left to go get clams. With regret, they left a ruddy sunset and soon found their friends with long face and cut hands...but no clams.

Yet another page has a small, exquisite watercolor painting of a lobster with the handwritten caption: “Ye hot lobster.”

Professor John Stilgoe, who teaches the history of landscape at Harvard University, first discovered the journal in a used book store while on a bike ride in Cape Ann in 1999.

On the counter inside, the leather-bound volume lay open, its pages an organic collection of cursive writing, watercolors and early photographs depicting women on a remote coast.

“I took one look at it and was staggered by its beauty,” he said.

He pledged to the bookseller that Harvard would buy it.

“And put down my own credit card and told him if Harvard didn’t buy it, I would buy it.”

Harvard pounced, buying the volume sight-unseen.

Stilgoe said he was not surprised the women knew how to describe, draw and paint the plants and seascape around them: He’s researched how educated American women in that era studied Latin and botany.

But Stilgoe’s discovery at the bookstore was not the first time the book had been rescued.

Ann Marie Allen is a retired chemist and theologian who helped solve the mystery. She said the journal has had several close calls, starting with that inaugural trip to the rustic cottage more than a century ago.

“When it rained, [the roof] leaked. It poured inside the house. And they talked about running around and getting buckets to catch the water. They talked about rescuing the book that we’re talking about — rescuing that log book from the deluge that was coming through the roof,” Allen said.

Preserved for generations to come

The last page of the journal is a watercolor painting of the island with the rickety cottage. In the margin is the handwritten note, “A small green isle — it seemed — no more.”

One of the essays the women read aloud was “Westminster Abbey,” a somber reflection by Washington Irving on the fleeting of time.

“And one of them made mention of memories, and things we leave behind for people to find out something about ourselves. And I just thought, those women quoted from or read that particular passage. Did they ever dream that their journal was going to be looked at over 100 years later?” Allen said.

Irving wrote: Time is ever silently turning over his pages; we are too much engrossed by the story of the present, to think of the characters and anecdotes that gave interest to the past; and each age is a volume thrown aside to be speedily forgotten.

But this leather-bound volume will not be forgotten. These modern-day sleuths have joined hands with the Friends of the Boston Harbor Islands to publish the journal in June. In addition to the original entries from 1891, their book will chronicle the detective work that led to the discovery of the travelers’ identities, with proceeds going to the nonprofit.

With the printing, it will preserve this snapshot of Boston Harbor’s history, and preserve the women themselves — under their own names.

GBH News intern James Bartlett contributed to this report.