Maybe it’s because I recently saw a trailer for the newest installment of Jurassic World that I had dinosaurs on my mind. But last week, a new studyby British paleontologist Dr. Jon Tennant caught my eye. In it, he described how over the last 25 years, discovery of new dinosaur species and specimens of species we already know have spiked — by a whole lot. Like, off the charts.

“Until around 1990 the rate of discovery of new dinosaur fossils was pretty low,” said Tennant. “And in the last 25-30 years we’ve seen this explosive growth in the number of dinosaurs we’re finding. We’re now in an exponential stage of discovery.”

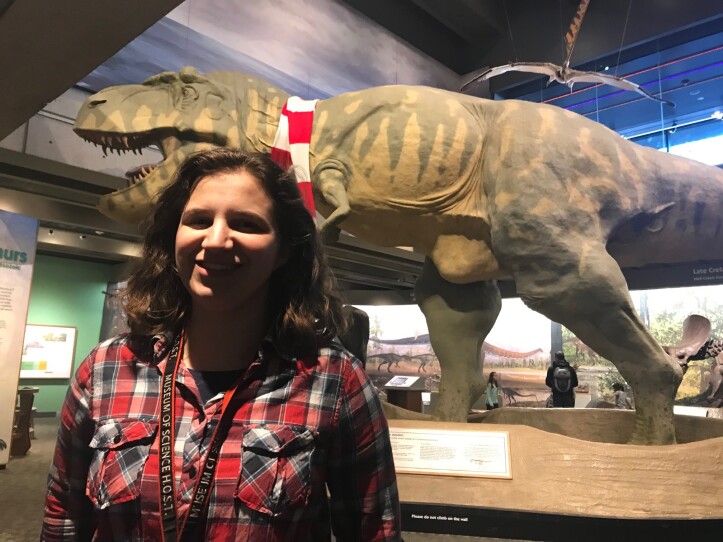

This got me curious as to why. And what, if anything, all this new discovery has meant for our understanding of dinosaurs. So, I headed to where else but Boston’s Museum of Science for answers.

"What the public knows, or thinks it knows, about dinosaurs is completely outdated," said Katie Slivensky, a paleontologist by training who now works in the museum’s education department.

She seemed the perfect person to drop some knowledge on me about the latest in ancient lizards. And she began by explaining why I was completely wrong to think of them as ancient lizards.

"Dinosaurs are warm-blooded or endothermic on the most part. They are active, they eat a lot of food to keep their bodies going all day," she explained.

And it’s not just being warm-blooded that makes lizards a terrible reference point. Sure, like lizards, many dinosaurs had scales. But, "a good number of dinosaurs had feathers," said Silvenski. "They had these covering their body."

And not just flying dinosaurs, but all kinds of dinosaurs. Even the famed T. Rex might have had feathers — at least in some places. And those leathery velociraptors made infamous by the Jurassic Park films?

"Velociraptor had feathers all over its body," said Silvensky.

So just why has there been such a spike in new knowledge of these 60-plus million-year-old creatures in the last 25 years? For one, says Slivensky, the approach to finding them has changed. Back in the day?

"They’d find the biggest, coolest fossil they could find," she explained. "The biggest skull, with the most teeth. And that is not a very scientific way of going about making discoveries."

These days, what’s hot is the small stuff. And the closer attention to the little things has led to an explosion in discoveries of new, small dinosaur species, and smaller versions of the big dinosaur we already know.

"What has not been studied very well until very recently was how dinosaurs grow up," explained Slivensky. "What do the babies look like? How do they go through different growth stages and get bigger and older? And they're starting to find some really cool things."

For example, the Limusaurus — a dinosaur discovered in 2009 — that would begin its life as a toothed omnivore and transform into a toothless, beaked herbivore as an adult.

And paleontology it’s no longer just bones and fossils.

"Paleontology used to be a little more geology-focused with a dash of biology, and it’s definitely skewing now biology-heavy," said Slivensky.

And so, microbiologists are studying minuscule things that survive for eons on fossils — like proteins and melanosomes, tiny specimens that dictate an animal’s color. Slivensky says there’s still some debate about whether these melanosomes were truly left by the dinosaurs.

"But the evidence is piling up to say these came from the dinosaurs," said Slivensky. "These are legitimate melanosomes that are telling us that this dinosaur was red, or black or iridescent."

Add to this mix new technologies. The rise of the internet has made information sharing easier, and in recent decades, Chinese scientists have entered the global paleontology community in earnest — a boon for collective knowledge. Then there’s the newest way to analyze dinosaur fossils.

"I think one of my favorite things that is happening right now is that we’re starting to take these fossil impressions and shoot them with lasers," said Slivensky.

These laser scans produce detailed images — beyond what scientists ever dreamed possible — revealing skin and feather nuances, muscles and ligaments not visible to the naked eye.

So much of what Slivensky had to say was new to me, but what really blew my mind was when she stopped me mid-sentence the first time I said the word “extinct.”

"Dinosaurs aren’t extinct," she said. "We can still study them today. They’re birds."

EBH3: Birds are dinosaurs?

KS: Yes.

EBH3: Sparrows are dinosaurs?

KS: Sparrows are dinosaurs

EBH3: Chickens are dinosaurs?

KS: Chickens are dinosaurs. You’ve probably eaten dinosaurs.

And so, as genetics and behavioral scientists learn more about living birds, it aids paleontologists in their understanding of their venerable ancestors. And Slivensky says that link is also important on another level — a reminder of the real-world truth in that line made famous by Jeff Goldblum in the first Jurassic Park film 25 years ago: "Life finds a way."

"To understand that these birds that are flying around you right now are dinosaurs and they are what this successful group of animals have become, I think can just hammer home the idea that we are connected through time all the way back to the beginning," said Slivensky.

And as the new discoveries keep piling up, there’s no telling what riches the future holds for our understanding of that distant past.

As always, I want to know what has you curious these days. Email me at curiositydesk@wgbh.org and let me know. Who knows, I might just look into it for you.